Through his debonair but very Bengali detective, Satyajit Ray left an indelible impact on Bengali, and Indian, culture. In the year of the writer-filmmaker's centenary, a look at the most popular and iconic character he created.

Why Feluda remains the ultimate Bengali cultural icon – Ray centenary special

Mumbai - 24 Apr 2022 0:08 IST

Updated : 25 Apr 2022 15:26 IST

Shriram Iyengar

In the same year that he completed his iconic Charulata (1964), Satyajit Ray was working on another goal. A couple of years earlier, he had restarted the publication Sandesh, a family legacy. Founded by his grandfather, Upendrakishore Ray, and run later by his father, Sukumar Ray, the periodical was a premier children’s magazine in Bengali.

In 1964, Ray was in search of short stories to drive the magazine’s readership of young adults and teens. He took up the pen himself, following up his Bankurbabur Bandhu (Alien) with a young boy’s adventure with his sleuthing older cousin, Feluda.

Titled Feludar Goendagiri (English title: Danger in Darjeeling), the story would become the origin of a truly Indian hero with a Bengali identity and a global outlook. It was a short story that soon morphed into a cultural icon that has left an everlasting imprint on Bengali literature.

Ideal Hero

Young, handsome, with a rebellious streak combined with a strong moral code, Feluda was the aspirational Bengali ideal. No surprise, as Ray modelled Feluda upon himself. Filmmaker Srijit Mukherji, a Feludaphile,said, “Feluda encapsulated the image of the international Bengali. He was the prototype of what Satyajit Ray was, very very Bengali in his food habits, in his dressing, living, his love for Kolkata, but at the same time, the world came to him. When he spoke English, he was more English than the British.”

Of course, another of Ray’s greatest influences was British through and through. A fan of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s creation Sherlock Holmes, Ray embedded Feluda with Sherlockian friends. A Moriarty-like Meghlal Maganraj, Mycroftian Uncle Shidhu, and, of course, Topshe after Watson. In his story Londoner Feluda (Feluda In London), the detective from 21 Rajani Sen Road even stops at 21 Baker Street and says, "Guru, we would not have been here without you."

In his interview with director Shyam Benegal, Ray said, "Of course, Topshe is the Watson to Feluda." Naive, but with a keen ear for what Feluda says, Topshe was the satellite through whom teenagers lived Feluda’s story.

Author Diptakirti Chaudhuri was one of those teenagers. He told Cinestaan.com, “I was a kid and when I saw Feluda for the first time on the screen, I wanted to be the sidekick!” Chaudhuri said everyone wanted to be with Feluda, not like him. “Feluda is the elder cousin we all wanted," he continued. "All of us looked up to him. There is always a genius in the family who does not take the usual path. Feluda is that guy. None of us, without exception, ever wanted to be Feluda. We wanted to be Topshe.”

Chaudhuri is not alone. Even director Sandip Ray, son of Satyajit Ray, wanted to be Topshe rather than Feluda.

Between 1965 and 1992, Ray’s adventures of Feluda, translated in multiple languages, became a staple for a new generation of Indians. Illustrated by Ray himself, these spreads in the magazine were imprinted onto young minds.

Filmmaker Sagnik Chatterjee is familiar with this phenomenon. On the 50th anniversary of the iconic character, he released a documentary, Feluda: 50 Years Of Ray’s Detective, to underline the impact the character had on generations of Indians.

Puja Tradition

Speaking to Cinestaan.com, the filmmaker said, “I started reading Feluda first with The Incident in Kathmandu. I remember the novels which came in Desh's annual Puja magazine. It had a doublespread illustration, which Ray used to do himself.”

The Durga Puja annual is a cultural tradition which continues and has enriched the legacy of children’s literature in Bengal. Diptakirti Chaudhuri said, “If you go down the list of every major Bengali writer, everyone, without exception, has written for children. Right from Tagore to even Saratchandra Chatterjee, to people in the current space, or recently passed, like Sunil Ganguly, have written children's literature. There is some truth to the stereotype about reading Bengali.”

This tradition has resulted in a bevy of detectives who have enriched Bengali literature, and continue to do so. Feluda’s peers included Sunil Ganguly’s Kaka Babu, Nihar Ranjan Gupta’s Kiriti Roy, and Ray’s own Professor Shonku. He was preceded by Sharadindu Bandopadhyay’s famed Byomkesh Bakshi. This plethora is unlike any other regional literature in India. While detective fiction has always been popular, it has never gone mainstream as it did in Bengali.

Srijit Mukherji attributes this thirst for fictional detectives to the historical legacy of the city of Kolkata. As the capital of the British Raj until 1911, the scientific pursuit of criminal investigation put down roots in the city. Mukherji pointed to the fact that the use of fingerprint tracing in India began with the Kolkata police. "Since Kolkata was the capital of the British in India till 1911, Scotland Yard would work in close association with the Bengal police. The sense of mystery, crime and investigation is old. Priyonath Mukhopadhyay, detective turned author in Bengali, goes back to the 19th century. We have a very rich history of actual case solving and investigation.”

Cultural Signifier

Yet, Feluda transcended generations when it came to popularity. Despite Ray’s rise as an auteur whose cinematic language transcended India, he admittedly owed his immense popularity in Bengal to the fan mail for Feluda than for his movies. For a filmmaker who used understatement as the key marker for his cinematic language, the cult and mass popularity of Feluda seems like an aberration.

The reason lies in the construction of his stories as something more than adventures. These stories were cultural markers embedded with international literature, cinema and tidbits about many cities in india and abroad. Several generations before Google, this information was invaluable.

“Feluda's interests are similar to those of Ray," Sagnik Chatterjee said. "Being a voracious reader, if Ray read something interesting, he would give a reference of the book in Feluda's novel. You have to remember that at that point of time, we had no Google or any means of social communication. Feluda was a source of gathering information for youngsters.”

Author Chaudhuri measures this influence on three levels — cultural, geographical and moral. “The first part was books, movies, foods, dressing style, cigarettes, among other things," he explained. "Very influential. Many people woke up to Tintin because of Feluda. Second thing was many locations. Feluda's stories are like guidebooks. I went to Gangtok [in Sikkim] on a family holiday and carried his book. It is exact. If he says that this monastery will take 1–1½ hours, it took exactly that. In Bombay, there is this restaurant called Copper Chimney, which finds a mention. I remember when I first got a job and was meeting a friend in Bombay, he said, 'You must treat me at Copper Chimney.' It was like a guidebook for us.”

From Lucknow (Badshaher Angti, 1967) and Gangtok (Gangtokey Gondagol, 1970) to Rajasthan (Sonar Kella, 1971), Bombay (Bambaiyer Bete, 1976), Kathmandu (Joto Kando Kathmandute, 1980) and Hong Kong (Tintorettor Jishu, 1981), Feluda travelled the world and, with him, his many young Topshes, too.

Feluda takes up martial arts and mentions Bruce Lee. He reads Tintin and discusses movies. For a teenager in 1970s Calcutta, this was a window to the world.

The third element, everyone agrees, is the strong morality of Ray that is reflected in these stories. Chaudhuri said, “Satyajit Ray had a very strong morality. But this morality was never preachy. I don't claim that all Bengalis became better human beings on reading Feluda, but these things stayed with you.” Hence Feluda’s almost self-deprecating apologies when he had to smoke. He would carry a .32 Colt, and was a good shot, but never shoots to kill.

One reason for this moral code was the domain of children and young adult literature that Feluda falls in, Srijit Mukherji explained, “Apart from women characters and crimes of passion, graphic content in terms of sexuality, I think apart from these which were left out because the target audience was young adults and children, there is nothing childish about the plots, the adventures... the prose is smart and crisp.”

Cinematic Transformation

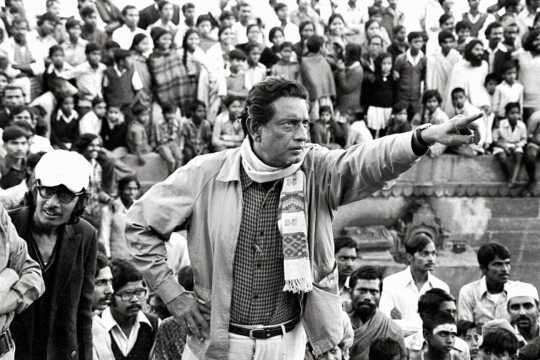

In 1974, Ray decided to transplant his cultured detective to the big screen like Sherlock Holmes. He directed Sonar Kella (1974), the first of many Feludas to arrive on the screen. Played by the late Soumitra Chatterjee, the film gave birth to the iconic ‘magojastro’ (intellectual weapon) and a new iconography. Since then, several actors from Sabyasachi Chakraborty to Abir Chatterjee, Parambrata Chatterjee and Tota Roy Chowdhury have played the iconic role.

Even the late Shashi Kapoor made a short appearance as Feluda for Sandip Ray’s Hindi mini-series for Doordarshan, Kissa Kathmandu Mein (1986).

Srijit Mukherji said, “Cinema being such a powerful medium, it has dominated the understanding of Feluda. In fact, most people see Soumitra Chatterjee as Feluda. Though physical feature wise Soumitra Chatterjee is dissimilar to Feluda, they liken him to the character because of his intelligent portrayal, his eyes especially.”

Sagnik Chatterjee believes each actor has embodied a different facet of Feluda. “I first saw Feluda as Soumitra Chatterjee, but my youth was with Sabyasachi Chakraborty," he sad. "Soumitra Chatterjee was good at some attributes. He was not very physical, unlike Sabyasachi. Feluda practises martial arts. You cannot think of Soumitra Chatterjee doing karate. What Soumitra Chatterjee was good at was magojastro. It was defined only through films. This word, you cannot find in books alone. He moulded Feluda in a way that the actor fits in. No one actor can embody Feluda.”

It seems inevitable that even an insight into Ray’s literary skills deviates into cinema. The man’s genius achievements in the field often overshadow the fact of his multi-faceted skills. Diptakirti Chaudhuri said, “This has often been said about Ray: while he was good at 10 different things, if he had chosen to do one thing in his life, he would still be a genius.”

Mukherji added, “Ray made music for his own films, as good as a Salil-da [Chowdhury] or RD Burman. When it came to short story writing, he was as good as an O Henry or Saki. When it came to films, we know what he did. He was a polymath. The Renaissance man after Tagore.”

Visual Writing

So, how did Ray the author fare, especially through his Feluda series? According to Sagnik Chatterjee, “Feluda is more interesting because of the language. In Feluda, the language was devoid of any pre-colonial hangovers.”

Another element is the visual style that Ray adopted in Feluda stories. A filmmaker to the core, his illustrations, and descriptions, often captured the scene in its exact visual manner. Srijit Mukherji said, “When I was making Chinnomastar Obhishaap [part of the web-series Feluda Pherot (Season 1)], I hardly had to do any screenwriting. His stories are so pictorial, dialogues so crisp, you don't have to do much. Unless you want to interpret it in a different way.”

Chatterjee concurred, “If you read Feluda carefully, you can find influences of scriptwriting present in the novels. It is a peculiar mixture of literature and cinema. There is a portion where audio takes precedence, or the visual is important. These elements could narrate the entire story.”

In this mix, the Feluda series strikes a balance between adventure and serious literature. The closest rival, perhaps, would be the Harry Potter series, which addresses larger themes of humanity, courage and loyalty through the prism of children’s experiences.

Chaudhuri pointed out, “Ray never spoke to his child actors as one would do with children. Many of us kiddytalk, mollycoddle children. He would speak to them as with an adult. He would explain the context to his child actors. If you read his books, he is one of the best short story writers in the world. In terms of suspense, humour and supernatural elements, they were brilliant. If I read it now as a parent, it still scares me.”

Mukherji has been living with the author Ray for a while. He was working on the Netflix anthology Ray (2021) at the time he spoke to Cinestaan.com, adapting the author’s short stories on screen. “Ray the author is very underrated," the filmmaker said. "Which is why I am glad that Netflix is doing this series and we have a chance to showcase him as an author.

"He was the guy who brought science fiction to India. His Bankurbabur Bandhu (Mr Banku’s Friend) supposedly inspired E.T. (1982). Feluda is still extremely popular among teens and young adults. When I made Feluda Pherot, the avalanche of feedback I got, overwhelmingly positive at that, is one of the high points of my career.”

But how difficult is it to transposit an analogue detective story to an age of Google and social media? Mukherji admitted, “It depends on the stories. Certain stories are difficult to adapt to contemporary times because the plotting is not very technology agnostic. Given modern technology and investigative methods, CCTVs, DNA, you will crack Feluda stories very easily. For those stories, you will have to give a spin. Certain other stories are technology agnostic, those can be made up for these times.”

Chatterjee explained, “In Feluda, you have Uncle Shidhu, a mentor. He is the Mycroft to Feluda. Why would you need an Uncle Shidhu when you have Google and search engines?” But he added: “Many things have changed, but the process of being human has not changed. Evolution has happened technically, scientifically, but the basic nature of human beings remains constant. The emotions of anger, hatred, jealousy remain the same.”

It is a mark of the genius that was Satyajit Ray that he, as a part-time author, could capture themes that have stood the test of time. Three decades since his death on 23 April 1992, Feluda continues to capture the imagination. Mukherji has been preparing for the second season of Feluda Pherot.

Chatterjee describes the character as a 'cultural legacy' passed down through generations, quite like Tagore’s Rabindra sangeet. “For four generations, it has been downloaded into their [youngsters'] veins.My father is 77, he also reads Feluda and watches movies, my son does, and so do I. It is the same as Tagore's Rabindra sangeet. Now, few youngsters may truly understand Rabindra sangeet. But at some point of time, these youngsters have heard their mother or grandmother singing, and will listen to it.”

Chaudhuri agreed: “Honestly speaking, in terms of the number of books, Feluda would still be the highest-selling series in Bengali. Even now. I routinely see books going out of print and coming back in print.”

Chatterjee put it succinctly. “Ray passed away in 1992. This is 2021,” he said. “Every year, on his birthday, there is no formal invitation, but people who love him, grew up with his writings, show up at his doorstep. Every year 1,000 or 1,500 people show up. It never happens in any corner of the world for a director/filmmaker/author. There has been nothing new from him since 1992. But the impact he has had till now, generations since, Y or Z, their love for him is very striking for me.”

If one were to make so bold as to apply Albert Einstein's plaudits to Mahatma Gandhi to Ray, it would not be out of place. Generations to come, particularly those with decreasing attention spans, will find it hard to believe that one man could inhabit so many facets, and with such excellence. Is it any surprise then that he created an icon who embodied similarly complex facets? A veritable superhero who has lived on through generations, and, like Ray himself, continues to find admiration from newer generations.

Corrections, 25 April 2022: An earlier version of this feature referred to a character named Uncle Shibu who is a mentor to Feluda. The character's correct name is Uncle Shidhu. Also, the actor who has played Feluda is Sabyasachi Chakraborty and not Mukherjee.

Related topics

Satyajit Ray Centenary