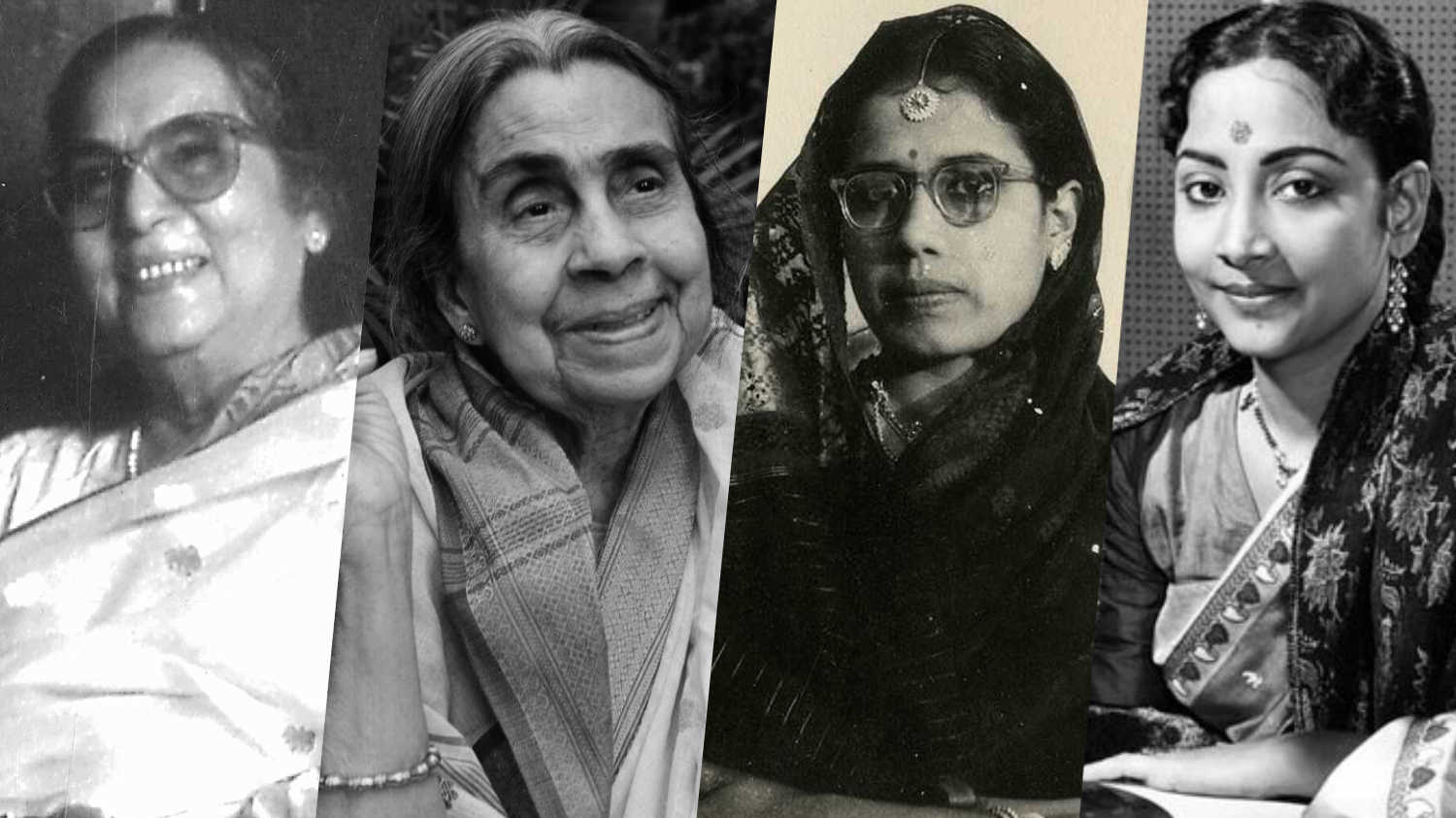

On International Women's Day, Cinestaan looks at the creative and gifted wives of filmmakers who, for reasons best known to themselves, chose to vicariously bask in the reflected glory of their spouses’ excellence.

Women whose talents were subsumed by marriage to famous men

Kolkata - 08 Mar 2021 19:02 IST

Updated : 05 Apr 2021 12:14 IST

Shoma A Chatterji

A beautiful exhibition of photographs clicked decades ago by the late Manobina Roy, one of the first female amateur photographers in the country, threw up a whole lot of questions around the wives of celebrities who led their lives in the shadows of their respective husbands. Whether they were happy living this way or whether it did not even occur to them to reinforce their distinct talents and bring them into the public space, no one knows. But the fact remains that most of them spent their lives as wives and mothers and efficient homemakers whose focus was entirely on the family and for many, their talents died with them or, maybe, many years before they died.

Manobina was the wife of one of the most renowned filmmakers in Indian cinema — Bimal Roy. Sadly, this exhibition was organized by his son, Joy, youngest daughter Aparajita and their late second sister Yashodhara on Manobina's centenary, so she will never know the tribute that has been paid to her through this exhibition.

But Manobina is neither the first such woman nor the last among this increasing tribe whom we may box together as “vicarious wives”. The functions of a vicarious wife are held to be outside the work orbit of her husband but very much inside the system in which the husband functions, which makes her contribution all the more ambivalent. The irony in the lives of women like Manobina, Jyoti Chowdhury, Geeta Dutt, Bijoya Ray, Gita Sen and Surama Ghatak is that they remained “invisible” as talented women once they were married.

They are ‘invisible’ because their contributions to their husbands’ careers were neither recognized nor rewarded. Yet, these contributions can easily be measured in terms of the heights of excellence, recognition and reward the husbands reached because, without the active participation of their wives, they might never have reached those heights. The willingness of these women to forfeit their own careers, interests or talents is as if structured with the marriage itself. Not all these men were famous when they married. But as they attained fame and excellence, their wives slipped into the role of ‘vicarious wives’. Whether this participation was willful or not is beside the point. The point is that the cultural map of the fields they might have enriched with their individual contributions was rendered poorer by their absence.

Jyoti’s three daughters, who are grandmothers themselves, recently organized the very first exhibition of their mother’s paintings and sketches at a hurriedly put together exhibition in Mumbai. Jyoti is 92 and can no longer move out of her house. She is the estranged wife of the late great music composer, lyricist and writer Salil Chowdhury who left her and their daughters to set up a second family. While they were together, he encouraged her to go on painting, would buy her books on artists and their works, and even began painting himself.

Let us track back into the past to dig out more such examples. Bijoya, wife of Satyajit Ray and also his cousin, was an extremely gifted vocalist born into a family steeped in music. The four sisters — Gauri, Sati, Jaya and Bijoya — were all noted for their talent in music. But after she married Ray, she turned her focus to partnering with her husband in many ways. Among these was that she was the first one to read his scripts, accompany him to his shoots both in studios and on location, help him with costumes and discuss every scene with him. Though this was public knowledge, she chose to lead a low-profile life like a shadow of her husband. She translated his childhood memoirs Jokhon Chhoto Chhilam but only after he had passed away. Most of us have never heard of her having acted in a Bengali film, Shesh Raksha, in 1944. She did half of the embroidery we see in Charu’s hand in the opening frames of Charulata (1964). Why did she remain in the shadows of her husband? Now, we shall never know.

Surama Ghatak was an educated woman and trained teacher who supported her husband Ritwik Ghatak through his struggles to find a footing in films. She was also imprisoned when her husband was behind bars for participating in the freedom struggle. She wrote two wonderful books in Bengali that trace the rise and fall of her husband. In one of these, she wrote about her experiences in prison.

Surama was a political activist even before she had met Ghatak and since the theatre was her passion, she was attracted to Ghatak after seeing him in a play. She stood solidly by his side during his trials in prison and her diaries give a glimpse into the deep empathy she had for her husband. They separated later when he became an incurable alcoholic and was in and out of mental hospitals. By then, she had taken up the job of a teacher and brought up and educated her three children only to lose both daughters and even a granddaughter to early deaths and only son Ritaban to psychiatric hospitals. She died, forgotten, on 7 May 2018, aged 92. But those who met her never heard her grumble or complain or seek sympathy, so dignified was she as a person.

Gita Sen, wife of Mrinal Sen, was an actress in her own right who was forced into theatre at the age of 15 when her father, a freedom-fighting member of the Congress party, was released from prison because he was dying. Theatre was one of the several jobs she took up as the single earning member of a family in dire straits. But the theatre and then cinema brought her some notice and a little money.

Gita was a stage actress when she met her future husband and went on to have a very happy but financially troubled marriage for more than six decades. Following her marriage, she was rarely seen in films other than those her husband directed.

Her son Kunal, who is now in his sixties, said, “It remains a mystery why my father didn't think of using her until Calcutta 71. For some reason, he never thought of her as a film actress. She got offers from almost all the major film directors of that period, and she would either reject them or agree to them to finally back out at the last moment. I do not know why. It was certainly not due to any lack of encouragement from me or my father. But my father was at the peak of his career, so maybe Ma thought it would upset the delicate balance of keeping the household running if she stepped out of the house. We could perhaps have seen much more of her talent on screen if she were more selfish and less committed to offering solid support to my father and me and all the people we were associated with. But it is equally difficult to imagine how this could have had a direct impact on family life and on my father’s career as a filmmaker.”

Soumitra Chatterjee’s wife Deepa was an ace badminton player and a former state champion who quit the sport after her marriage. During his entire career, she had been his most forthright critic, ticking him off for what she felt was not good and praising him for what she felt was. What made her quit sports completely?

Geeta Dutt, the extremely talented wife of the great filmmaker Guru Dutt, lent her voice after marriage only to his films. Exceptions like her wonderful songs in Basu Bhattacharya’s Anubhav (1971) were rare. Hers was the only honeyed voice that complemented the nightingale voice of Lata Mangeshkar and they were also reported to be very good friends. No one knows why she gave up singing not only for films but also at live performances and recordings. Perhaps this self-deprivation, as the grapevine says, led her to alcohol and early death from cirrhosis of the liver.

None of the husbands is known to have placed any barriers to their wives’ talents. They were perhaps more liberal than the ordinary mainstream husband in urban India and quite open to their wives pursuing their personal and/or professional interests.

Webster's dictionary defines ‘vicarious’ as “experienced or realized through imaginative or sympathetic participation in the experience of another — acting for a principal — having the function of a substitute — taking the place of something primary or original.” The use of this word in current trends on research in women’s studies applies to women who fulfil their achievement needs either completely or predominantly through the accomplishments of their husbands. Tresemer and Pleck, who studied the reaction of men to the achievements of women in the US (1972), wrote: “American men are simultaneously living through their wives emotionally while the women live vicariously through their husband’s achievement.”

The irony in the lives of women like Bijoya, Gita, Surama, Deepa, Manobina and Jyoti is that while the wife’s participation is solicited, actively or passively, to sustain the husband’s creativity and pursuit of excellence, her contribution is taken for granted and/or sidetracked. This could be because recognition and reward might actually reduce the importance society places on the husband’s work. At times, the contribution of the wife to the husband’s career may well be greater than his own. But this is kept ‘invisible' even to the wife. Thus, we continue to produce generations of vicarious achiever wives who take great joy in basking in the reflected glory of their husbands’ fame and excellence! Our salute to these great women.

Correction, 9 March 2021: Shesh Raksha, the Bengali film in which Bijoya Ray played a part, was released in 1944 and not 1914.

Related topics

Women's Day