Esthappan, which won a National and as many as five Kerala state awards, is a work of abstract beauty which, at the same time, is tangible in its humaneness.

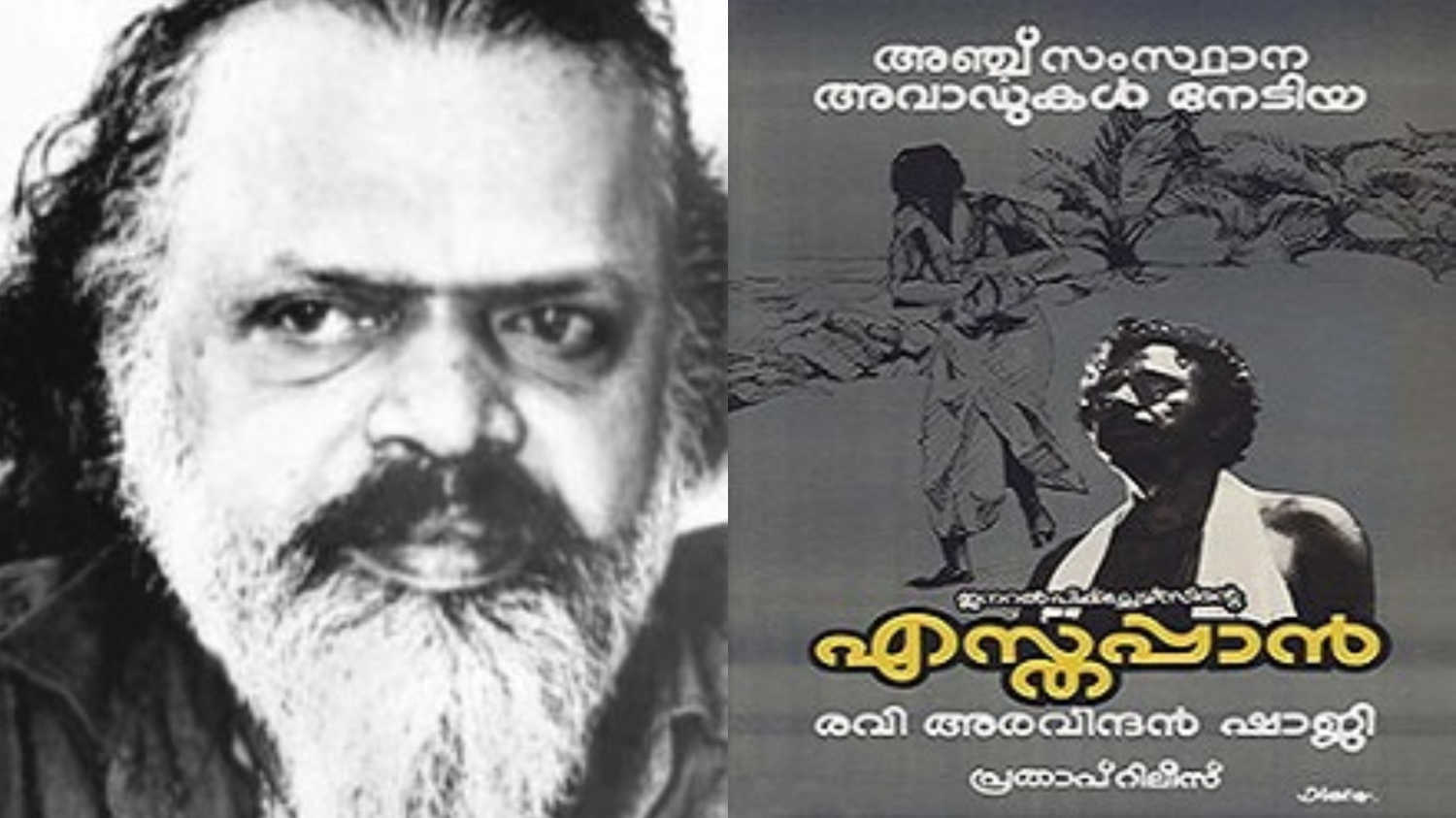

Rediscovering G Aravindan through Esthappan (1980) – Death anniversary special

Kolkata - 15 Mar 2021 20:43 IST

Shoma A Chatterji

Esthappan (1980), directed by G Aravindan, is almost universal in its theme yet ethnic in its essentially Indian identity. The camera glides gracefully across the seascape of the quaint fishing village which forms the backdrop of the film. The canvas is almost always a beautiful blend of blues and browns and greenery, speckled with the white worn by the protagonist Esthappan. Cinematographer Shaji N Karun, who evolved into an outstanding filmmaker over time, is aided in the enriching of his visual presentation by the richly embellished music provided by Aravindan himself along with Janardanan.

At Sunday morning mass in church, he is omnipresent with his quiet devotion to the priest who seems to be the one who knows the real Esthappan better than the rest of the village. Esthappan can work wonders. He can turn pebbles into sweets and delight the kids in the village. He can bring a sick girl out of her comatose condition just by waving his arm over her body. He cannot reproduce this, however, when the strongman of the village is present to laugh at his ‘non-existent’ magical powers. He is taken to be a thief and guiltily accepts the blame when he is actually shielding the real thief. The priest knows the truth and is surprised to discover this facet of the Esthappan mystique.

Esthappan has the instinct to smell danger for a little girl who wanders close to the sea at high tide. He distributes currency notes from a nondescript-looking jute sack till the currency floats in the air like a flock of birds in flight, perhaps making a mockery of man’s love for mere slips of paper. He moves determinedly across the village lanes immune to the stares, comments and remarks thrown to and at him, almost as if nothing about them concerns him anymore. The next minute he is bowing at the feet of an idol of Mother Mary, obviously praying for the tiny, comatose girl.

During the day and the evening, Esthappan is armed with his lantern of incense, while one night we watch him perform a witch dance with devil-like figures which throws up a rather eerie atmosphere. The sounds emerging from the figures are distinctly ghostly and shrill. Yet we never see Esthappan using his powers for evil. He is graceful in his own way though, looking at his countenance, this adjective might not fit him at first glance.

Legends around Esthappan float freely through the village and even among the elite. He thus emerges as a legend of sorts himself and the viewer emerges from the 'Esthappan' experience with a mixed feeling of floating somewhere between the credibility of a folk legend and the rationality behind a figure of mystique.

Aravindan also revealed a rare insight into setting and establishing the significance of an incident or event by focusing on the reactions of the people witnessing it more than on the event. This comes across in two scenes. One happens in the beginning when the villagers are attending the Sunday mass. The faces of the people are captured in close-up, the camera moving slowly and calculatingly yet with feeling over every face. This scene also introduces us to some of the other characters who form the supporting cast — the Westernized young man with his foreign wife, the priest, the other men who know Esthappan well. Another scene happens right at the end during the “magic” play when, once again, the faces of the viewers capture the camera’s attention.

Through the character of Esthappan, we get an insight into the lifestyle of an ordinary fishing village in Kerala. The fights, the miseries, the desperate poverty, the helplessness of a 'kept' woman who is thrown out by her 'master', the fatality of a dying child for the child’s mother are all fleshed out with feeling and empathy.

The miracle play at the end of the film is popularly known as Chavittu Natakam, which has its origins in Portuguese passion plays based on biblical stories and legends. It is a dying art now and performed only in the Latin Church during festivals. This miracle play is mainly presented through very long shots and the metaphorical connection with the Esthappan story does not come out all that well.

The film comprises artistes who had never faced a movie camera before. But with the amazing expertise of a gifted filmmaker like Aravindan, the film and the performances in it do not once degenerate into the dryness evident in films featuring non-professional artistes. Some of the cast, such as Rajan Kakkanadan, Krishnapuram Leela, Sudharma and Shobana, became known after this film. The music, composed and orchestrated by the director himself, is lyrical, mellifluous and lifts the film to a work of abstract beauty which, at the same time, is tangible in its innate humaneness.

Aravindan, who passed away on 15 March 1991 aged only 56, was a painter, a cartoonist and music composer and began his directorial career from the stage. The germ of the idea of Esthappan was born during a casual discussion with members of his theatrical troupe. The mainstream of the discussion percolated to each member being called upon to relate his or her unusual personal experience of some incident or individual that defied commonly accepted norms of human reason and common sense. The film won no less than five state awards in Kerala.

Aravindan's first film, Uttarayanam (1974), had a political slant dealing with the problems of youngsters born in India after Independence. The film exposed opportunism and hypocrisy against the backdrop of the Independence struggle, inspired by Aravindan's own cartoon series Cheriya Lokavum Valiya Manushyarum.

His next, Kanchana Sita (1977), was drawn from the Ramayana. The film, with a feminist slant, significantly differs from other adaptations of the epic in the characterization of the central characters, including Rama and Lakshmana.

Thampu (1978), shot in black and white, narrated the story of the continuous struggle of a theatre troupe and unfolded like a documentary. Kummatty (1979) was a Pied Piper-like figment of Malabar's folklore about a partly mythic, partly real magician called Kummatty which perhaps gathered strength and expression in Esthappan.

Pokkuveyil (1982) tries to probe the depths of the mind of the protagonist who is on the brink of insanity. The music for this film was composed by renowned Hindustani classical flautist Hariprasad Chaurasia. The legend is that visuals of this film were composed according to musical notations, without any script. The protagonist is a young artist who lives with his father, a radical friend, a sportsman and a music-loving young woman. His world collapses when his father dies, the radical friend leaves him, the sportsman friend gets injured in an accident and has to give up sports, and the woman's family takes her away to another city.

Chidambaram (1985) is a deeply symbolic exploration of the man-woman attraction leading to betrayal and eventually to the purgatory of guilt. The film tries to find out whether the morals inflicted by society on an individual would come to terms with his natural instincts. It was an adaptation of a short story by CV Sreeraman and was produced by Aravindan. The film featured Gopi, Smita Patil and Sreenivasan in the three main roles and is a deep socio-psychological analysis of guilt, belief, disbelief and intrigue.

Oridathu (1986) is the story of a village where electricity arrives for the first time. The film depicts the narrow-mindedness and hypocrisies of village lives with a sense of wry humour, focusing on how the lives of the villagers change forever.

Marattam (1988) is about the identification of an actor with his role. Here, three different plots of the same event are revealed and remain unsolved. Each version is accompanied by different styles of folk music of Kerala — Thampuran Pattu, Pulluvan Pattu and Ayyappan Pattu.

Vasthuhara (1991), set in Calcutta, is the story of displaced people who have lost their land, wealth and identity due to forced displacement from their roots to a city they are complete strangers in, both in their ignorance of the language and the culture and lifestyle.

Aravindan was often criticized for making too many films within too short a time. But he silenced his critics with his magical versatility, including the rich use of colours as a metaphor within his films, excellently discovered in Chidambaram. Except in his last film Vasthuhara, he never seems out of his depth and is in full command of his subject. He used colour in the most metaphorical manner, adding to the credibility of the backdrop and enriching the content of his films by using colour to fit the mood of a scene. The most ideal use of colour comes across in Chidambaram, which this writer saw without English sub-titles, and yet it came out very clearly through the visuals, the rich music and the nandanar songs in the backdrop.

The best comment on Aravindan came from the late film critic Iqbal Masud, who wrote, “All of Aravindan’s films have a transcendental edge… there is a sense of an uneffable meaning not only beyond the film but also beyond schematic explanation."

Postscriipt: Esthappan is not a new film. The film was premiered over forty years ago in 1980. But viewed 40 years later, it has not lost any of its topicality either in terms of the technique of film craft or in terms of its content. This writer watched the film at a surprise retrospective of G Aravindan’s films, where a special screening of his then latest film Chidambaram was held for an invited audience. None of the films had English subtitles because the organizers could not get hold of subtitled copies. This made no difference to those who did not know Malayalam. The films proved that cinema, if handled with the mastery it demands, is its own language.