The Kolkata International Film Festival handpicked five of the auteur's feature films and a documentary on one of his works to celebrate the filmmaker who would have turned 101 this month.

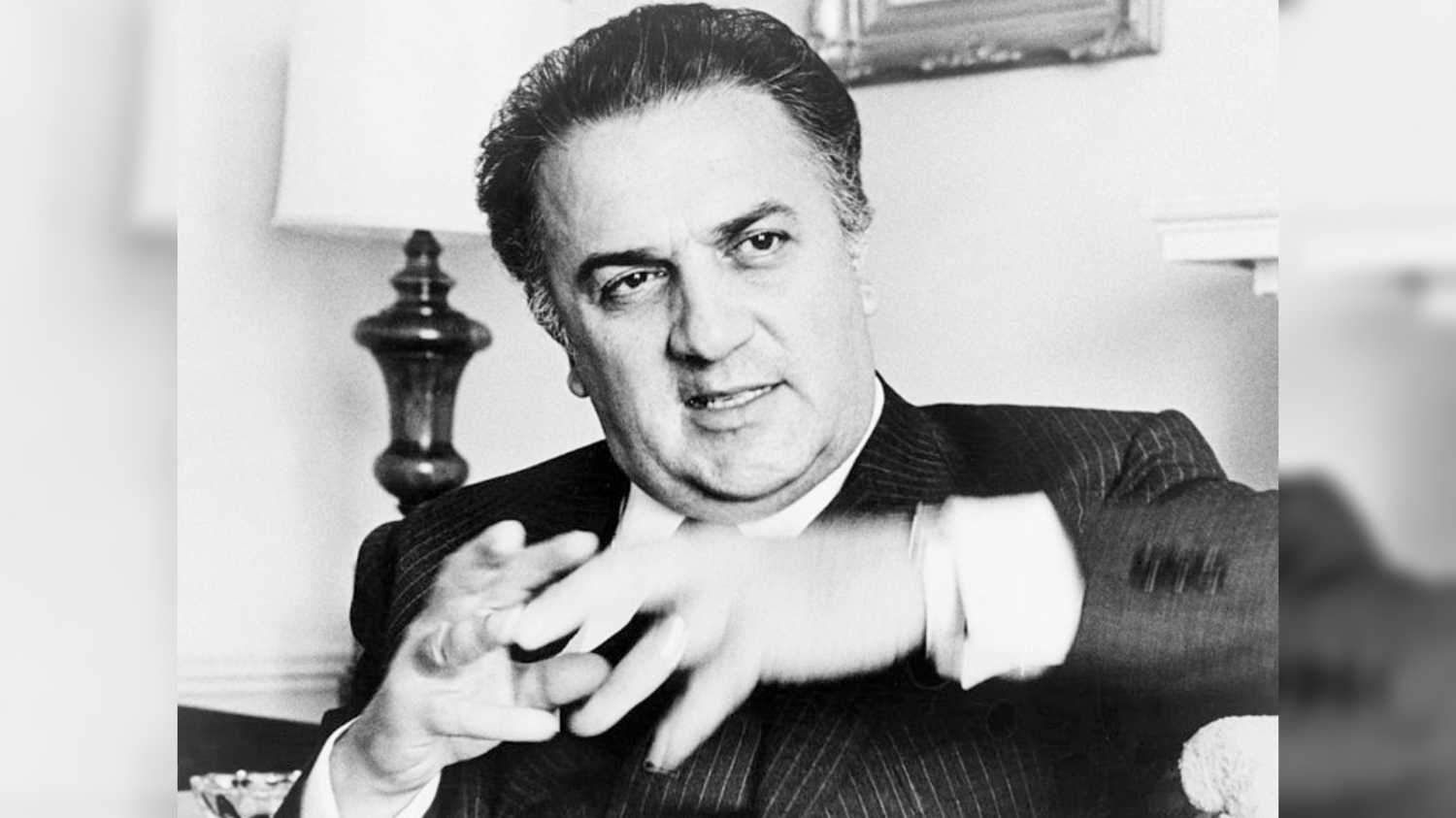

Federico Fellini: The dreamer who roused generations of filmmakers

Kolkata - 15 Jan 2021 23:58 IST

Updated : 16 Jan 2021 0:12 IST

Shoma A Chatterji

“A film is like an illness that is expelled from the body.” – Federico Fellini (1969)

Italian filmmaker Federico Fellini is synonymous with personal and highly idiosyncratic visions of society. His films offer unique combinations of memory, dreams, fantasy and desire. The adjectives ‘Fellinian’ and ‘Felliniesque’ are identified with extravagant, fanciful and, at times, even baroque images in art in general and cinema in particular. Felliniesque is used to describe any scene in which a hallucinatory image invades an otherwise ordinary situation. Renowned filmmakers like Woody Allen, Pedro Almodovar, Tim Burton, Terry Gilliam, Emir Kusturica, David Lynch, Girish Kasaravalli, David Cronenberg and Martin Scorsese have cited Fellini's influence on their art.

The term paparazzi, now in common parlance, was born in Fellini’s La Dolce Vita (1960), in which journalist Marcello Rubini (Marcello Mastroianni) derives it from the name of his photographer friend Paparazzo who photographs celebrities in every which way he can.

Two major films of Polish director Wojciech Has, namely The Saragossa Manuscript (1965) and The Hourglass Sanatorium (1973), throw up examples of modernist fantasies and have been compared to Fellini’s work for the “luxuriance of his images”.

The 26th Kolkata International Film Festival (KIFF), which ended today, picked five feature films by Fellini and a documentary made on one of his works to celebrate his centenary. In 2009, at the 15th edition of the festival, a few Fellini films were screened as part of a retrospective event and almost every single show was packed to capacity, underscoring the popularity the master's works enjoy among cine buffs in India in general and Bengal in particular.

Fellini had no formal training in filmmaking. He was born in the small seaside town of Rimini on Italy’s Adriatic coast in 1920 to Ida Barbiani and Urbano Fellini, a travelling salesman. He spent four or five years in a boarding school in Fano. The school was run by priests and as a truant student young Federico was often subjected to severe punishment. Slices of this truant childhood are reflected in I Vitelloni (The Wastrels, 1953) which shows youngsters leading an idle, aimless street life of truancy and wandering. Priests also found a place in many of his films.

Some say Fellini drew generously from his childhood experiences for important segments in his films, particularly I Vitelloni, 8½ (1963) and Amarcord (1973). But some of his associates such as screenwriters Tullio Pinelli and Bernardino Zapponi, cinematographer Giuseppe Rotunno and set designer Dante Ferretti had a different take. They insisted that Fellini invented his memories for the pleasure of narrating them in his films.

When he turned 18, Fellini quit the hopeless limbo of Rimini to go to Florence where he worked as a comic-strip illustrator with a magazine. Six months on, he moved to Rome and joined a bohemian set of would-be actors and writers. He did not pursue his degree at the law school he had enrolled in. Nor did he care to train in Rome’s Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia, though he collaborated with graduates from the school later on, when he was in films. He did not go to cinema clubs that screened outstanding films from Italy, France, Germany and Russia. He sometimes said his influences in filmmaking carried traces of the styles and approaches of Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Laurel and Hardy, the Marx brothers, Pietro Germi and Luis Bunuel. He also liked the works of Carl Theodor Dreyer, DW Griffith and Sergei Eisenstein.

He began to sell stories and cartoons to a humorous weekly, Marc’Aurelio, in 1939 and was soon hired as one of the writers of a radio serial based on the magazine’s most popular feature detailing the marital misadventures of Cico and Pallina. Still unfocused about what he really wanted to do, Fellini joined his friend, comedian Aldo Fabrizi, on an odyssey across Italy with a vaudeville troupe, making a living as a sketch writer, scenery painter, bit player and 'company poet'. Years later, in an interview, he said this was "perhaps the most important year of my life. I was overwhelmed by the variety of its human landscape. It was the kind of experience few young men are fortunate enough to have — a chance to discover the character of one’s country and at the same time to discover one’s identity."

In 1942, Fellini met Giulietta Masina who played Pallina in the radio serial. In 1943, they were married, marking one of the greatest creative partnerships in world cinema. Fellini died on the day after his 50th wedding anniversary while Masina died six months later.

Personal tragedy ensued soon after marriage, with Masina suffering a miscarriage followed by the birth of their son Pierfederico, who died a month after he was born, which is said to have inspired the conception of La Strada (The Road, 1954).

Soon after the fall of the fascist regime and the liberation of Rome in 1944, Fellini set up the Funny-Face Shop with friend Enrico De Seta, drawing caricatures of Allied soldiers for money. During this time, Roberto Rossellini approached Fellini. He wanted Fellini’s friend Fabrizi to play an important role in Rome, Open City (1945) and also wished Fellini would collaborate on the script.

Fellini accepted the assignment, writing gags and dialogue. For Rossellini’s next film Paisan (1946), he served as both co-scenarist and assistant director. During the film’s making, he wandered into the editing room, began to observe how Italian films were made, and discovered that they were quite a lot like the old silent films with an emphasis on visual effects, with the dialogue dubbed later. In 1947, Fellini and Sergio Amidei received an Oscar nomination for the screenplay of Rome, Open City. In 1950, Paisan received an Oscar nomination for the screenplay by Rossellini, Sergio Amidei and Fellini. Fellini had found his vocation.

On Rosellini’s request, Fellini wrote and acted in The Miracle segment of the anthology film L'Amore (1948). He played the part of a mute vagabond whom Anna Magnani, as a deluded shepherdess, takes to be St Joseph and who makes her pregnant. The film scandalized Catholic opinion everywhere and was considered outrageous.

In 1950, Fellini co-produced and co-directed Variety Lights (Luci del Varietà), his first feature film, with Alberto Lattuada. A backstage comedy set among the world of small-time travelling performers, it featured Masina and Lattuada’s wife, Carla del Poggio. Its release to poor reviews and limited distribution proved disastrous. The production company went bankrupt, leaving both Fellini and Lattuada with debts they took over a decade to repay.

The first film Fellini directed independently was The White Sheik (Lo Sceicco Bianco, 1952). It was based on a story by Michelangelo Antonioni who had hoped once to direct it himself. It was inspired by fumetti, or fotoromanzo, a genre of popular photographed cartoon strip romance magazines published in Italy at the time. Fantasy and reality mingle as they do in much of the master’s later works, though here the mood is comical and, at times, farcical. This was the first time Fellini worked with music composer Nino Rota, an exceptional artistic relationship that lasted till Rota’s death during the making of City Of Women (1980).

I Vitelloni got Fellini his first distribution abroad and won the Silver Lion at the Venice Film Festival. Translator and film critic Isabel Quigley called the film "one of the most profound social commentaries I have met in the cinema — the portrait, piercingly accurate, of a generation and a country’s dilemma; and the story, sour-sweet, hopeless, and always human, of five well-nourished, spiritually starved, not-so-young men."

Other critics see it as a step away from the social preoccupations of neo-realism towards the development of Fellini’s conception of character. Fellini himself said he was portraying not "the death throes of a decadent social class but a certain torpor of the soul". I Vitelloni inspired European directors Juan Antonio Bardem, Marco Ferreri and Lina Wertmuller and had an influence on Martin Scorsese's Mean Streets (1973), George Lucas's American Graffiti (1974), Barry Levinson's Diner (1982) and Joel Schumacher's St Elmo's Fire (1985), among others.

Fellini’s masterpiece La Strada won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, the first in a line of several Oscars and international awards to follow. La Strada is one of Fellini's most accessible and humane works, a film of understated beauty and profound insight. The theme of a soul torn between the heart and the mind is prevalent in Fellini's films.

La Strada explores the soul's eternal conflict between the heart and mind. Zampano (Anthony Quinn) is a cruel travelling carnival strongman who buys his assistant, a simple-minded young woman named Gelsomina (Masina), from her poverty-stricken family. Gelsomina is innocent and childlike. Masina's exquisite performance is as comical as it is heartbreaking. She does Zampano's bidding without question or resistance, though he is abusive to her. He abandons her in the street to spend the night with a woman. He lashes her with a tree branch when she misquotes her introductory lines. He forces her to steal from a convent. Yet, she remains faithful and uncomplaining.

Their fragile relationship is disrupted when Gelsomina meets The Fool (Richard Basehart), a witty circus clown. He mercilessly taunts the oafish Zampano, who can only react with violence. The Fool is kind and reassuring to the gentle, suffering Gelsomina, offering her a means to leave Zampano. It is the rivalry over her that precipitates the film's inevitable tragedy.

Produced by Dino De Laurentiis, Nights Of Cabiria (Le Notti di Cabiria, 1956) saw Masina reprise her role played in The White Sheik, as the star of the show. She haunts the Roman periphery, a lonely, irascible little prostitute with a grave professional handicap — a tendency to fall in love with men whose main concern is to shove her into the Tiber or over cliffs to acquire her modest savings. The film won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Film and brought Masina the Best Actress award at Cannes. The Broadway musical Sweet Charity was inspired by the film.

Few films have defined society in as caustic and honest a manner as La Dolce Vita (The Sweet Life). Marcello Rubini (Mastroianni), a frustrated writer, is reduced to tabloid journalism to make ends meet. He spends every evening in Via Veneto — the hotspot for people who want to be seen — vicariously awaiting the next scandal, party invitation, or sexual proposition. One evening is spent with an enigmatic woman named Maddalena (Anouk Aimee), whose dark sunglasses conceal a bruised eye. Her declared love for Marcello is merely whispered from a distance, deflected by the reverberating walls. Another evening is in the penthouse of Steiner (Alain Cuny), a wealthy intellectual.

Consumed by self-doubt and fleeting happiness, Marcello cannot enjoy his success. One more evening is spent with Silvia (Anita Ekberg), a famous actress. As dawn breaks, she gets back to her boyfriend.

Away from the nightlife of Via Veneto, Marcello finds himself caught up in the carnival spectacle of a false sighting of the Virgin Mary. The empty evenings soon seem to weave together some decadent rhythm, punctuated only by the regret of the following morning. Fellini visually conveys the cycle through stairs: the descent to a prostitute's flooded basement apartment, the climb to a church tower, the walk to a public fountain, the exploration of an unoccupied section of the princess dowager's estate. Thematically, the film begins and ends with the same incident: Marcello, unable to hear the cryptic message, returns to his latest distraction... perhaps still dreaming of attaining the elusive sweet life.

La Dolce Vita broke all box-office records. It was also awarded the Palme d’Or at the Festival de Cannes and is considered a quintessential film of the 1960s.

The film 8½ weaves fluidly through the visually intoxicating landscape of Fellini's subconscious, seemingly to seek inspiration and validation for his life and work. In an opening scene that symbolizes much of Fellini's cinema, a suffocating man, trapped inside his car, suddenly begins to float into the skies, only to be abruptly tugged back to the ground. But it is an indelible image that shatters any preconceived illusion of "typical" elements in a Fellini film.

The film 8½ literally marks Fellini's work on 8½ feature films (the "1/2" derived from collaborative direction films) and was a transitional film in his artistic career. This was his last film shot in black and white. The film replaces the subtle forms and religious iconography of his earlier neo-realist films with precisely composed, comic absurdity and exaggerated, hyperbolic imagery — of what became his signature, the typical Fellinisque style.

The protagonist, Guido Anselmi (Mastroianni), is the filmmaker's celluloid alter-ego who embarks on a surreal, introspective journey. A successful director of films "without hope”, Guido goes on holiday to an exclusive health spa to overcome a creative block. But he is neither suffering nor tortured. He is narcissistic and self-indulgent and prefers to spend his time networking with wealthy resort patrons and arranging liaisons with his oversexed mistress Carla (Sandra Milo) instead of formulating ideas for his next film.

Guido’s words contradict his actions. In essence, he is searching for balance: between childhood traumas and idealism, the sensual and the intellectual, artistic integrity and commercial success. Inevitably, Guido is as much a reflection of Fellini as he is of us — striving for greatness, only to achieve the ordinary and familiar, with episodes of momentary abstractions.

Fellini’s films garnered numerous awards, including four Oscars, two Silver Lions, a Palme d'Or and a grand prize at the Moscow International Film Festival. In 1990, the filmmaker won the prestigious Praemium Imperiale, a global arts prize awarded by the Japan Art Association. Considered the equivalent of the Nobel, the award covers five disciplines — painting, sculpture, architecture, music and theatre/film.

The women who both attracted and frightened Fellini and an Italy dominated in his youth by Mussolini and Pope Pius XII inspired the dreams that the director started recording in notebooks in the 1960s. Many of his films like 8½ or Fellini Satyricon (1969) are influenced by the work of the Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung and his ideas on the anima and the animus, the role of archetypes and the collective unconscious.

Fellini lies buried in the same bronze tomb as his wife and their son, located at the main entrance to the cemetery of Rimini. It would be appropriate to close with a beautiful quote of his: “There is no end. There is no beginning. There is only the infinite passion of life."

Related topics

Kolkata International Film Festival