Celebrating Earth Day on 22 April, we revisit the legendary filmmaker’s project about the water crisis which was well before its time.

50 years of Do Boond Pani: KA Abbas’s prescient film about the water crisis and its impact on human lives

New Delhi - 22 Apr 2021 17:00 IST

Sukhpreet Kahlon

Screenwriter and journalist-turned-filmmaker KA Abbas deployed every medium at his command to communicate his thoughts and ideas. Firmly dedicated to humanist ideals, his debut feature Dharti Ke Lal (1946) exposed the greed and callousness that had led to the Bengal famine, which killed millions of people. With the keen insight of a journalist and the zeal of an evangelist, he delved into themes of exploitation and highlighted the condition of the marginalized in several films such as Neecha Nagar (1946) and Jagte Raho (1956), which were written by him; Rahi (1953), Shehar Aur Sapna (1963) and Hamara Ghar (1964). In Do Boond Pani (1971), Abbas turned his attention to a crucial problem — the acute water shortage in certain regions in Rajasthan and the ways in which this affected the lives of the people there.

The idea to make a film on water scarcity came from the then-Prime Minister, Lal Bahadur Shastri, who had informed Abbas that the world’s biggest canal was being built in order to bring water to Rajasthan from Punjab. Shastri suggested to the filmmaker, “Why don’t you make a film about this great human drama?”

The ‘human drama’ is the story of Ganga (Jalal Agha), who brings his new bride Gauri (Simi Garewal) to his village in Rajasthan, which is thirsting for water. His old father Hari Singh (Sajjan), is a farmer obsessed with the idea of growing crops on his land and laments the lack of water for irrigation. When Ganga watches a newsreel about the ambitious canal project, he is inspired by the romantic tale of Shirin and Farhad to work for the project and become a part of the dream of bringing water to the arid region.

As an educated woman, Gauri recognises the importance of the dam and encourages her husband to work on the site. While Ganga dedicates himself to the project, back home, his family faces several hardships. In the end, as Ganga sacrifices himself for the larger good, his wife inaugurates the dam and in a symbolic scene, the blood of Ganga becomes the lifeline for the region, through the gushing water.

Do Boond Pani clearly follows the developmental rhetoric of building the nation through dams, bridges and roads, and it ends on a hopeful, celebratory note, with the birth of Ganga’s son, Jamuna, and the life-giving waters of the canal finally quenching the thirst of the villagers.

The film takes us into the heart of the larger environmental concern by situating it within the lives of people who live with water scarcity every day. The opening credits juxtapose the skewed scenario where on the one hand, women are travelling miles by foot to fetch water and taps run dry in front of a long line of vessels, while on the other, people are bathing their pets and enjoying dips in swimming pools. With insightful dialogues and scenes, the film reiterates that the people of the village cannot think beyond their lifeline, water. In the scene when Ganga brings his new bride home and the father enquires about her, he is less concerned about her looks or beauty, wanting to know instead if she is strong enough to fetch two pitchers of water across long distances.

Though the story centres around the fate of Ganga’s family, Abbas interweaves several other concerns in the narrative: the education of women, the general apathy of the government towards developmental projects — signified through Lambu Engineer (Kiran Kumar), and concerns about the water crisis, drought and large-scale migration of people due to an inhospitable environment. In the current scenario, where we have started witnessing mass migration due to climate change, the film seems eerily prescient.

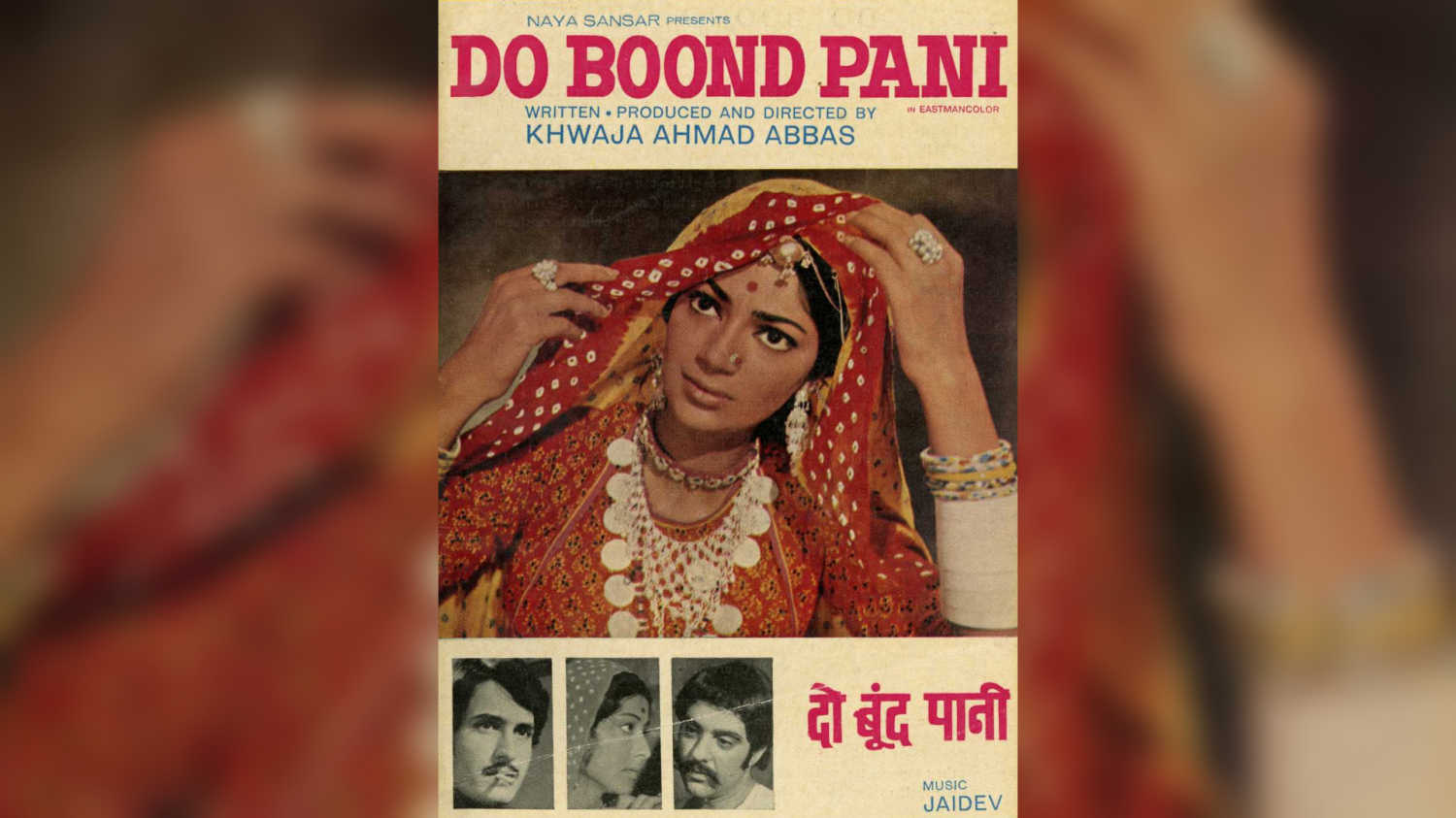

Describing some of the hurdles that came his way in the making of the film, Abbas wrote in his autobiography, “I had to contend with the star system which ordained that the poorest heroine could look like a beauty queen. We had provided a beautiful dress and jewellery to make Simi look like a Rajasthani bride. She is a very good artiste, remembered her dialogue, and even enacted them according to the Rajasthani dialect…But when it came to ‘make-up’, she would not listen to the make-up man and arrived looking like a Rajasthani princess who had never carried a pot of water on her head nor trekked miles across the burning sand.”

The film was largely shot on location, which lends a certain authenticity to the story. Travelling in the third-class compartment of the train, with modest, camp-like arrangements for the cast and crew of the film, was part of the no-frills filmmaking style of Abbas, where every member of the crew pitched in to do odd jobs. Recalling the shooting Abbas said, “Quite a few actors were tricked by my question: ’Are you going to stay with me, or are you going to stay with Simi, Jalal Agha and Ramachandra, the cameraman?’ Naturally, they thought that the producer-director would have a fancy place for himself and so they landed in our old house, sleeping on the floor. It has been my maxim that the producer-director must stay with the lowliest of the low technicians and not with the stars or the so-called stars.” Not only did Abbas’s films reflect his ideals, his lifestyle did too.

The film did not do well commercially though it did win the National award for the Best Picture on National Integration. The film's songs 'Peetal Ki Mori Gagari' and 'Ja Ri Pawaniya Piya Ke Des Ja', written by Kaifi Azmi with music by Jaidev, are perhaps the most remembered element of the film.