The National and Filmfare award-winner discusses the importance of sound design to the narrative in the past and present and how technological changes and OTT platforms have encouraged experimentation.

90 years of Sound: A lot of new ideas are coming from regional cinema, says veteran KJ Singh

Mumbai - 12 Apr 2021 14:17 IST

Updated : 19 Apr 2021 11:16 IST

Shriram Iyengar

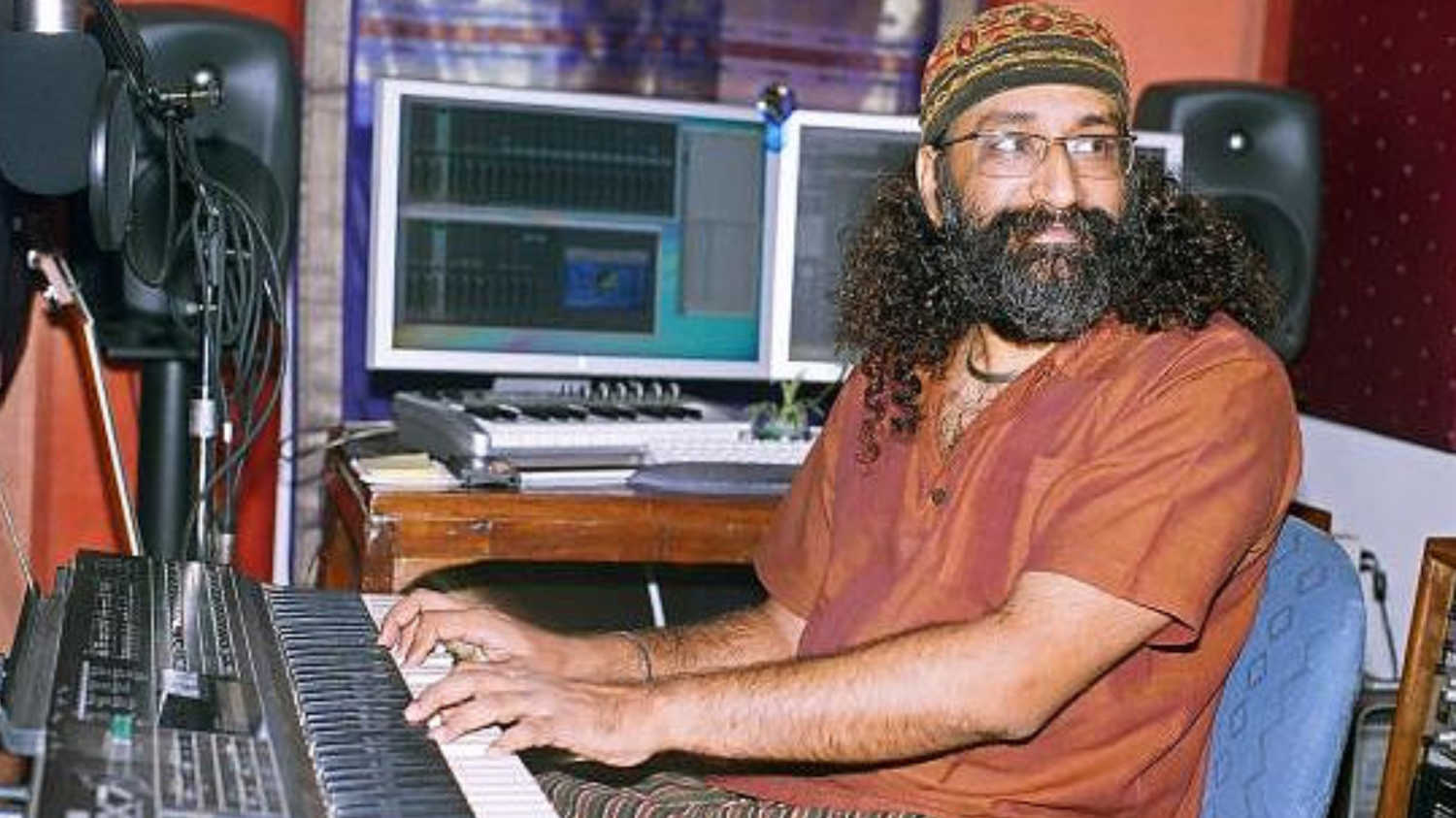

Sound design is a part of cinema that few viewers notice, and fewer appreciate or understand. KJ Singh aka Kanwarjit Singh Sawhney is among those who have made it their life's work to create, understand and articulate this technical part of the art of cinema.

With a career spanning over three decades, KJ Singh has been the quiet hand behind a number of popular films like sound mixing for Chachi 420 (1997), Satya (1998), on sound design for Makdee (2002), Maqbool (2004), and Omkara (2006). He has been part of mastering the albums for Rang De Basanti (2006), Black Friday (2007) among others. He was awarded the National award for Best Audiography for Omkara (2006) as well as the Filmfare award for Best Sound Design for the same film.

A sound engineer, designer, music producer, and guitarist, KJ Singh owns the production house Fast Forward Productions and is the chief of the independent music studio Asli Music. In an e-mail conversation with Cinestaan.com, he shed light on the mostly unexplored (by the ordinary viewer) space of sound design.

Sound design is not just about adding effects to a scene, he explained. The designer has to account for the emotional aspect of the scene and what the director is trying to convey. "And this is where it can get confusing for a viewer since both sound design and music are used as tools to enhance emotions in a story," he said.

From Mani Ratnam's observation of exactly how the chorus in a song should sound to Indian cinema's continuing failure to use silence effectively, Karanjit Singh Sawhney patiently explained, over several e-mails, the complexity and nuances of sound design in cinema. Excerpts:

Sound design is a crucial part of filmmaking and yet it seems the craft is still evolving. Are we right to assume that it is only now that the field is gaining prominence? Is the lack of attention a flaw on the part of the audience, filmmakers, or the media that does not shed enough light on it?

Earlier, the sound design of a film was taken care of by the same person who did foley and sound effects. Also, there were hardly any sound effects libraries available. I think only BBC libraries existed. Most sound recordists had their own personal sound libraries, collected over a period of time, from different shoots, that would be put to use when doing effects. Lastly, technology was still in its nascent stage of development; thus, track count was limited. Hence, there was not much room for experimenting.

Having said that, one has to give credit to the sound engineers of those days that they managed to achieve so much complexity in their work. The unforgettable helicopter sound merging into 'This Is The End' in the opening scene of Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979) was thanks to Walter Murch, who is credited as the first engineer to receive the title of sound designer for his work on that film, for which he won his first Oscar in 1979.

In India, it's relatively recent that all things have come together and now we have a separate title as well as a team of sound designers who look at designing the sound of a scene and the film, different from foley and background music. Here I must admit that the media, as well as various award organizers, give very little visibility to the sound design department. In some awards, it is not even a category!

For a majority of Indian audiences, sound and music are often synonymous, despite the massive difference in treatment and approach. Where does this difference lie? And what makes a sound design stand out?

Synch sound effects match the visuals for a sense of realism. What we see, we hear. One needs to hear the sound of a door closing when one sees a door closing in the visual. But sound design is not just putting effects on a scene. As a sound designer, you have to take into account the emotional aspect of the scene, what the director of the film is trying to convey. And this is where it can get confusing for a viewer since both sound design and music are used as tools to enhance emotions in a story.

Sound design is the whole treatment of a scene, especially with non-synch effects (which are not visible like synch effects). Sometimes the design is in the increased reverberation time or an echo build-up of the dialogue to denote over-thinking or paranoia. Or muting everything to make it a silent scene to enhance suspense. The decision of whether the AC hum in a room is going to serve as a sinister tone versus the slow-moving sound of a creaking ceiling fan is also a part of sound design. Using the sound of a passing train, even when you do not see any train, to highlight either loneliness or the parting of people is another simple example. The faraway water-pump sound in Omkara (2006), when Deepak Dobriyal comes to meet Ajay Devgn right after the latter had taken Kareena [Kapoor Khan] away, worked as a sound denoting awkwardness and tension. There was no need for any music there. So you can make the sound design stand out using familiar sound elements but in unusual ways.

Have filmmakers paid similar attention to sound design and its role in the texture of their stories in the past? How involved were/are filmmakers in the process?

This is largely a director awareness area. If the director is sensitive to the sound part of his/her film, then the end result is far more engaging. Vishal Bhardwaj, for instance, has come from a music and sound background. Hence, working with him on the sound design was a great experience.

Discussions on sound-design aspects would begin at the stage of the script getting finalized. This helps in instructions going out to synch sound engineers to try and capture certain sounds while shooting. If they have a good sound design/supervisor's head, then certain decisions, regarding whether to keep music or sound effects as the foreground, during the mix, can be taken care of before the film gets into the mix stage, avoiding last-minute battles.

Sholay and the magic of Mangesh Desai's sound design – 45th anniversary special

Certain directors were sensitive to the sound-design aspect in the past, and you can hear the attention to detail in their films. Sholay (1975) is one such film that comes to mind immediately. But recently there have been many films that have a fabulous sound design, like Kahaani (2012), Madras Cafe (2013), Baahubali (2015).

You have worked with filmmakers like Gulzar saheb, Vishal Bhardwaj, Imtiaz Ali, Gautham Menon, among others. Music is a prominent element in their works. How important is it to synthesize the sound design, music, and cinematic elements together in a project? How does the process come together, if you will?

Cinema is a collective experience of visual and sound. They have to work in tandem. I believe it is important to have a sound supervisor for a film who has the sensibilities for music and audio. When all aspects of the film are discussed at the writing stage, it helps to ideate and plan things ahead. During spotting (when the director sits with the sound effects person and the music director after the edit to mark where to do what), pointing things out and discussing them in detail helps a lot.

Working closely with the sound-effects team and the music team, one can manage to integrate each of the separate elements into a meaningful, emotional whole. Since both music and sound effects are treated as independent departments, they actually come together at the mix stage, where final decisions are taken. Most experienced and sensitive directors understand this and you can make out from their films how important music and sound are for them. All the above-mentioned directors, including Mani (Ratnam) sir and Rakeysh Omprakash Mehra, have a good musical ear and keen sense of sound and they are 100% involved in the ideation and creation of all these elements.

I once remember Mani sir (Guru, 2007) chiding me for making the chorus sound bigger in 'Ek Lo Ek Muft' than his shoot. It was a small chorus that he had heard in the shoot mix and hence had used dancers in that proportion.

Similarly, Gulzar saheb wanted me to keep the reverb tail as long as the shot mix in the ending of the song 'Tim Tim Taare' in Hu Tu Tu (1999), otherwise, for him, the scene would be a lie. That's the kind of involvement these directors have in the sound part of the film.

On the other side, how important is it for a sound designer to understand and interface with the filmmaker's idea to build the right sonic atmosphere?

Film is a director's baby and medium. Everyone has to be in sync with the director's vision. Each department is encouraged to give suggestions and options, but ultimately it's the director's decision what he/she wants to keep and what to let go of. So it is important for a sound designer to be in sync with the story and the director's vision of it.

I find that aesthetically they both have to be on the same page, having some similar references and likes and dislikes. It just makes for an easier working space. And the earlier the sound designer is on board the team, the better it is for everyone. I remember reading in MIX magazine that the entire sound design team of the film The Hunt For Red October (1990) spent weeks in the swimming pool of one of the team members, trying to record sounds underwater to use for design later on.

How has the process of designing sound for a film, or a music album, changed over the years? Are the changes simply technological? Or is there a difference in approach, production or collaborations?

Actors and directors are becoming sensitive to sounds, especially when doing synch-sound movies. Directors, technicians, artistes and viewers, all are now open to new ideas and expressions. Technology, as I mentioned, has helped to make experimentation a pleasure. But that has also given designers artistic freedom to put forth new ideas and soundscapes. Due to online operations, collaborations have become possible, giving way to serious niche areas. For example, one can now get access to gun cutters or chase cutters, people who specialize in designing gun battles or car chases.

Conversely, sound designers from India are doing amazing work for international projects. Interestingly, a lot of new ideas on sound design are coming from regional cinema rather than mainstream. Malayalam, Tamil, Telugu and Marathi cinema are paving the way in sound design. Baahubali is a leading example.

Technology has, evidently, made some things faster and better. But are there elements or aspects of sound designing that have continued as a practice, despite the change? Perhaps as tradition, or since it is simpler and more effective?

I think foley recording is the only surviving art from the early days of cinema. Though there is now software that can mimic a foley artiste, this specialization is still the fastest way of doing it. Slowing down tape playback to achieve lower-pitched sounds, bouncing from a recorder to the other to create more tracks or an echo effect are all things of the past that can be achieved far more accurately and easily than before. And recording sounds through a microphone has not changed in the last 100 years!

Have the developments in technology, not just for filmmakers and technicians, but also in terms of facilities for audiences, changed how sound design is approached or appreciated?

Absolutely! Computers have come to play an important role as they offer a fast search in database sound-effect libraries, mixing and mangling various tracks of sounds, morphing sounds with various plug-ins with the ever-safe option of 'undo'. Similarly, moving from mono to stereo to 5.1, then 7.1, and now to Dolby Atmos, has given audiences a widely immersive watching experience. Not only at cinema halls, but this has filtered down to home viewers as well. OTT and broadcast platforms are also offering a similarly immersive experience, as long as you have the playback hardware to hear it. So all this has exposed audiences to world cinema, raising their expectation and appreciation.

What does Indian cinema lack in terms of understanding or creating a good sound palette? Or does it lack anything at all? Are there any films that you feel have had technically excellent sound design in recent years?

How to use silence... we are still very insecure about leaving silences in scenes. International films use silences as an instrument, to highlight things in the scene. We have yet to learn to be comfortable with silences. Mostly as makers of the film rather than the audience.

Sound design by default gets a place to shine in sci-fi films, horror, or in stories where there is no previous reference to sound. This provides a clean canvas for the designer to create a totally new sound. Remember the lightsaber sound of the Star Wars series? Or Chewbacca talking or the computer pings of R2D2 talking?

India does not really make too many such movies for sound designers to sink their teeth into. Films like Pari (2018), Trapped (2017) and Bhoot (2003) had good sound design.

Has the OTT space allowed sound designers, like writers and cinematographers, to expand and experiment with techniques, ideas or styles?

Oh, yes. OTT platform sits right in the middle between TV broadcast and cinema, though closer to the latter, in this regard. The whole world is now watching what you have created, without having to move mountains to get that audience. Since everyone is on an international platform, this has pushed the envelope for all to make their story stand out at par with the best of them. This is almost like when streaming platforms became available. Your song could be playing before or right after an international artiste. So comparisons would be inevitable. To stand and be counted, you had to make sure your song stood at par — if not better — with the ones before and after.

Everyone is experimenting with techniques, ideas, styles, genres and bending, mixing, mangling, squishing sounds to make way for a new soundscape for the visual medium. Interestingly audio stories are making a huge comeback where sound design, yet again, plays a very important role, more so when there are no visuals!

Correction, 14 April 2021: An earlier version of this interview mentioned KJ Singh's full name as Karanjit Singh Sawhney. The correct name is Kanwarjit Singh Sawhney.