Basumatari's documentaries, Mhari Topli Ma: Basta and Mhari Topli Ma: Phang, which explore shifting food trends among tribals, were screened at the Rising Gardens Film Festival.

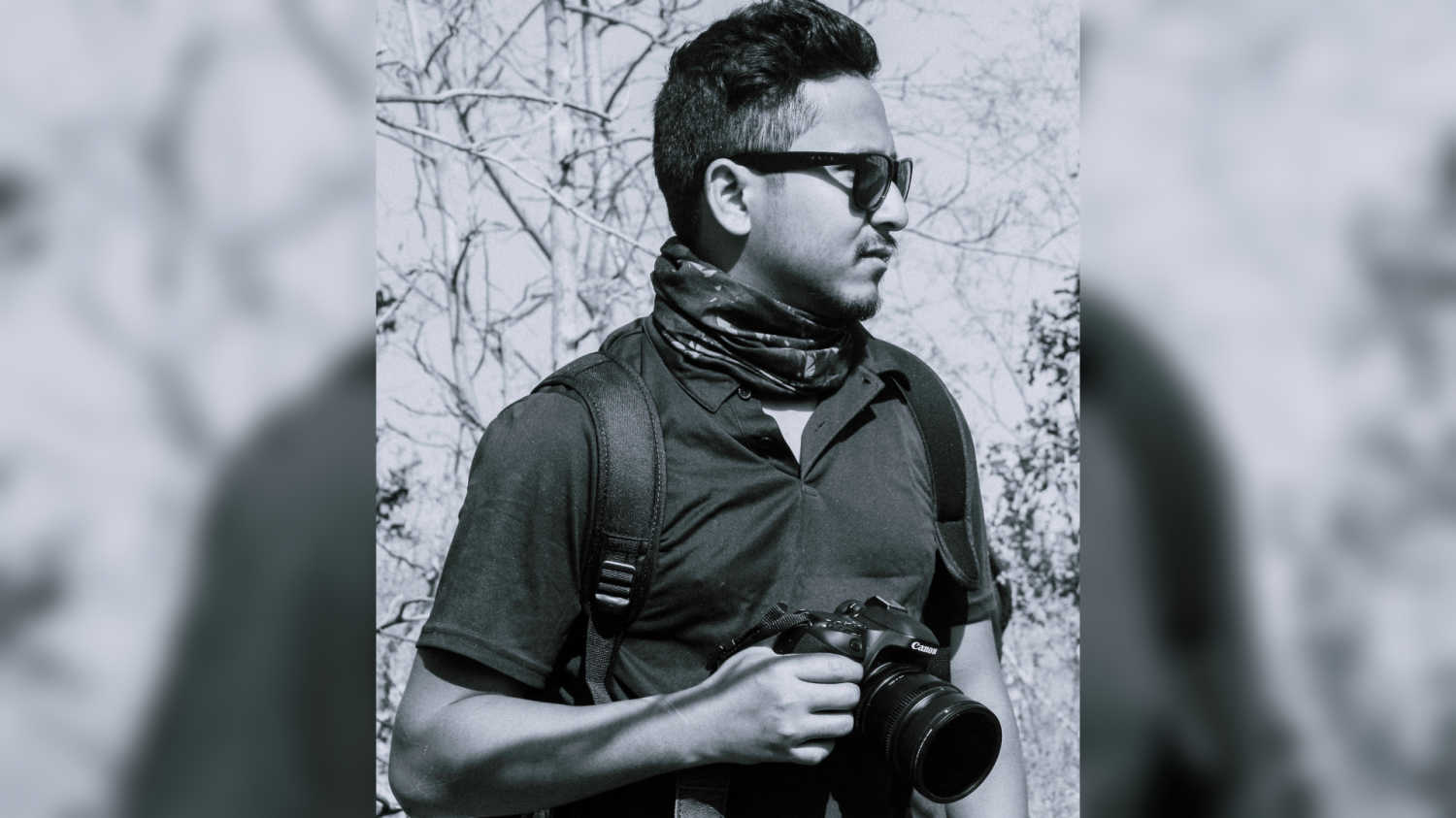

The younger lot thinks eating Maggi and chips is better than eating jowar, says Akash Basumatari

New Delhi - 12 Apr 2021 19:32 IST

Sukhpreet Kahlon

While eating a meal, we seldom pause to think where the food comes from and the many varieties of plants and grains that we are missing out on as a result of the gradual homogenization of our plates. Akash Basumatari’s short documentaries Mhari Topli Ma: Basta and Mhari Topli Ma: Phang explore traditional food practices in the tribal villages of the Narmada valley.

Mhari Topli Ma translates as In My Basket. Phang (Midnapore creeper) and Basta (tender bamboo shoots) are rich sources of nutrition but are rapidly disappearing as food items owing to changes in the attitude and lifestyle of tribal people.

Initiated by SPS Community Media at Samaj Pragati Sahayog (SPS), a grassroots organization working in Madhya Pradesh, the project is documenting uncultivated edible plants which were a major part of diets since ancient times amongst the indigenous Bhil, Bhilala, Barela and Korku communities.

The films concentrate on non-domesticated plants that grow naturally in the forests and are highly nutritious. However, with large-scale farming practices and the presence of hybrid seeds and weedicides, many of these plants are not found in abundance any more. In addition, these wild plants are disappearing from the plates of indigenous communities with the growing popularity of wheat and rice and changing attitudes towards indigenous crops.

An alumnus of the School of Media and Cultural Studies, Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS), Mumbai, Basumatari has been involved in film projects pertaining to issues like malnutrition, food sovereignty, early marriage and poverty.

“I have been always interested in making films on issues like this, particularly on the marginalized, which is why I joined SPS," he said. "They have an interesting community media going and have been working on nutrition, which is a major issue there as every house has a malnourished person.”

Though bound by similar concerns, both films engage with different tribal communities in the Narmada valley area in Dewas district of Madhya Pradesh.

“The tribes have been settled there for some time, so have gathered knowledge about wild edibles," Basumatari said. "There was no wheat consumption or any of this mainstream food available then. They used to grow jowar, millets. Jowar and wild edibles were the main foods.

"Then this cultural assimilation happened, so now there is a stigma attached to consuming wild edibles. If an Adivasi goes to a doctor and says I had this herb, the doctor looks down upon him and sees him as junglee [savage], so there is a certain shame attached.

"With the new generation, it’s more. The youth is influenced by popular culture. Basically, they like gluten now and can’t digest jowar.”

Traversing the changing food trends and the gradual disappearance of indigenous crops and plants, Basumatari pointed out, “The taste palette was completely different and they [the tribal people] are so nostalgic about it, the taste and the benefits. The region is very poor and famine and drought were routine, but till the time jowar was available, they did not worry much because jowar grows anywhere.

"Then this wheat cultivation and vegetables like ladies' fingers, onion, etc came in. Along with that came weedicides and pesticides. The wild edibles grow side by side with the crops, but they stop growing with the use of weedicides.”

The two films are an ethnography of the lives and customs of the tribal communities as they delve into the practices, customs, even local songs that accompany the picking, cleaning and preparation of these traditional food crops.

It is ironic that while in the cities there is now a move towards the adoption of indigenous crops and a gluten-free diet as well as awareness of the benefits of traditional grains and foods, there is the opposite impulse amongst the keepers of our forests and those who used to live in harmony with it.

“It’s not just about food, but it’s also a cultural shift, about how dominant cultural practices are taking over the minorities," the filmmaker said. "This is all connected. People then did not have money, but they were healthy. Now the youth is so influenced by popular culture and there is so much material need, they refuse to do manual agriculture.

"There used to be a barter system and people did not need liquid money, so people were healthy, the culture was intact, but now there is so much need to educate [them] and agriculture is so expensive because you have to use hybrid seeds. Because of all this, there is a culture of using money to consume food. The younger generation thinks eating Maggi and chips is better than eating jowar and looks upon roti, bhindi [okra] and paneer [a soft cheese] as more 'civilized'.

"In fact, they don’t even admit that they eat non-vegetarian food. There is a dominant image that is put down upon them that if you eat non-vegetarian food you are not civilized.”

The films were made for the community and disseminated through the mobile cinema project. The short documentaries are accompanied by print material that seeks to document other foods and cuisines to bring awareness within these communities.

The films were screened as part of the third edition of the Rising Gardens Film Festival last month.

Related topics

Other