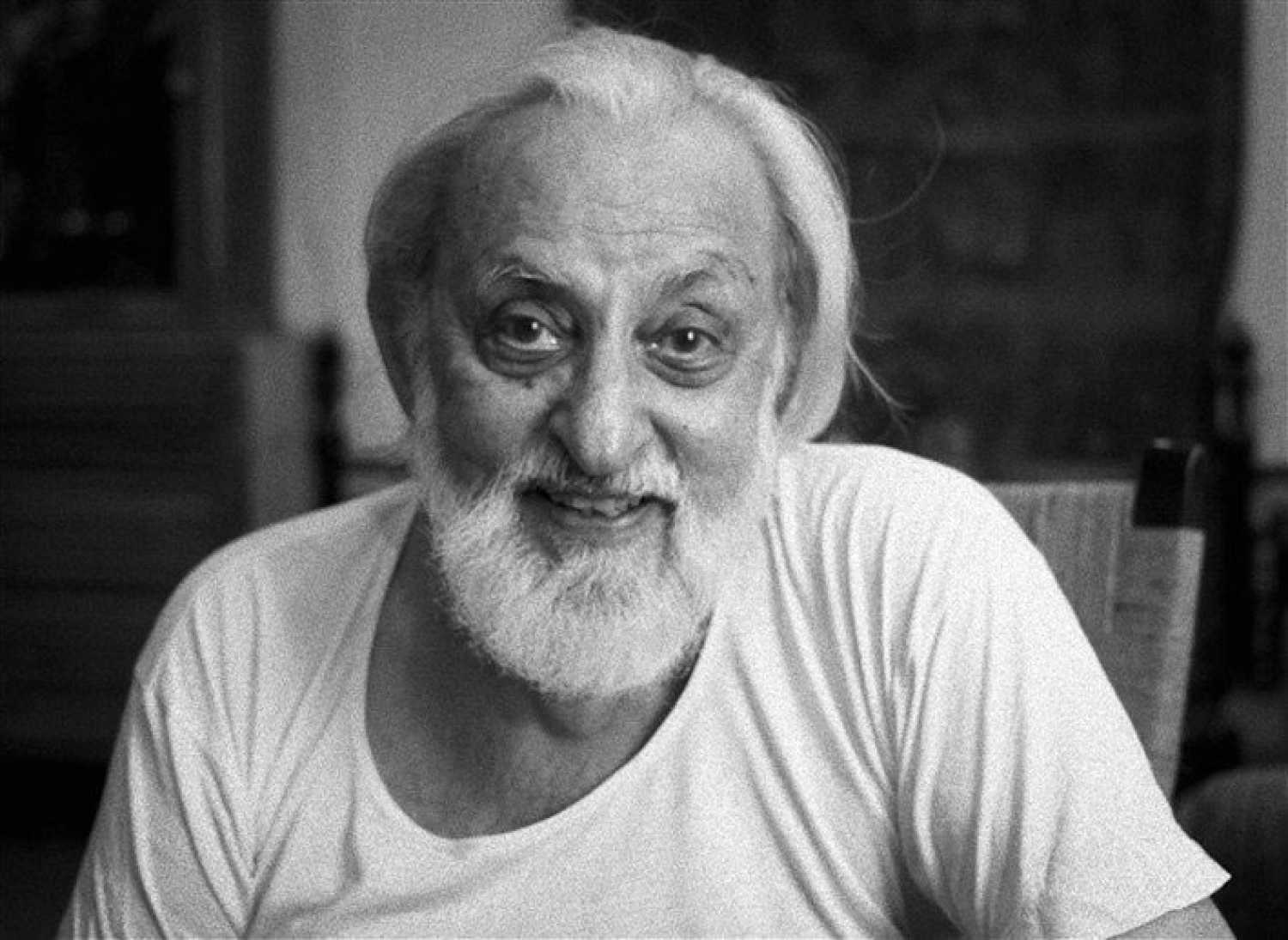

Garm Hava, the directorial debut of MS Sathyu, who turned 90 earlier this month, became both a milestone and a millstone for him.

MS Sathyu, filmmaker who scaled a peak in his very first attempt

Kolkata - 18 Jul 2020 18:30 IST

Shoma A Chatterji

I met the great director MS Sathyu serendipitously once. This was at Mumbai's Jehangir Art Gallery where his wife, scriptwriter Shama Zaidi, and he had come to attend their daughter Seema Sathyu’s maiden one-woman show of paintings. I recognized him at once as the director of Garm Hava (1973) but was so awestruck by his presence that I could hardly speak.

I was then reviewing art exhibitions for a financial daily and had only just started writing on cinema. The couple approached me with a smile, anxious parents wanting to know my response to the paintings. I merely smiled as I was not supposed to express my opinions. I soon left the gallery with a heavy heart for not having gathered the courage to nail him down for an interview.

Sathyu's given name is Mysore Srinivasa Satyanarayan, but the abbreviation has stuck with him forever. I met him many times later at film festivals and screenings but never did gather the courage to approach him because for a long time Garm Hava was the only film of his I had watched and I felt it would be wrong to talk to him on the basis of a single film when he had made other significant works in Kannada and Hindi. Unfortunately, I never had the chance to interview him thereafter.

Sathyu was born in Mysore on 6 July 1930 and turned 90 earlier this month. From his boyhood days, it was the fine arts that drew Sathyu, but his father, like most middle-class fathers, wished for him to take up science. So, after school Sathyu pursued a science in science.

Constantly disturbed by his passion for art, however, Sathyu left college mid-way and decided to go to Bombay to pursue a vocation in some line of art. He was interested deeply in theatre, too, but his interest there was focused on production design and costumes rather than on direction or acting.

The young man was scared how his father would react to his sudden decision. “But, surprisingly, my father did not object at all. I requested him to send me a money order for Rs50 every month to tide over my teething troubles in a new city. He agreed and continued to send me the sum every month,” Sathyu recalled once in a long interview. He freelanced for a while as an animator.

After being without regular employment for nearly four years, Sathyu got his first salaried job with filmmaker Chetan Anand. The director, who had seen Sathyu's work in a play, asked him to join as an assistant. “I requested him to appoint me as art director, but he said he already had an art director, so he wanted me to assist him," Sathyu said in the interview.

"I was stunned. I had hardly any knowledge of Hindi or Urdu, the dialogues of the film. I could not read the script, but he made difficult things seem quite easy and I learnt, slowly. But my mind remained focused on production design, art direction, costume design and also make-up. I got that chance later. But working with Chetan Anand was a learning experience.”

Sathyu satisfied his creative urges by designing some costumes for Chetan Anand's art director. Chetan Anand eventually gave him his break as chief assistant art director for Anjali (1957), planned as a tribute for the 2,500th birth anniversary of the Buddha.

A period film, Anjali required sets of the Buddhist era which Chetan Anand fully relied on Sathyu to create. The young man also created some of the costumes. One sequence in the film was an 800 foot take without dialogues in which Bhikshu Anand (Chetan Anand) is meditating and the chandalini's daughter (Nimmi) tries her best to disturb him as she is in love with him. The sequence was shot in one take and so impressed was Ustad Ali Akbar Khan that he composed four different tunes for the shot. Chetan Anand used the second composition for the background, purely created on the sarod. But no one talks about Anjali any more. The film was a flop. Nimmi was no longer in demand and Chetan Anand was a better director than actor.

Sathyu was part of a few more projects with the filmmaker after which he moved to Delhi and found a job with the Link-Patriot newspaper group. “I was in charge of page layouts [at the newspaper] at a time when technology was almost antique if you look back today,” he said.

Sathyu also worked for the Okhla theatre which later became the Hindustani theatre. “My first play in Delhi was Shakuntala, presented in Urdu, and we got a lot of flak from the media and audience for using Urdu as the lingua franca for a classical Sanskrit play. My argument was that if we can stage Shakespeare in many world languages, what was the harm if we did a classical Sanskrit play in Urdu?” he explained.

Sathyu’s keen interest in theatre made him part of many plays, Dara Shikoh, Mote Ram Ke Satyagraha, Amrita, Mudrarakshas, Aakhri Shama, Girija Ke Sapne (with the Indian People's Theatre Association), Rashomon and Bakri (a political satire) being the more significant ones. He was presented the Sangeet Natak Akademi award in 1994 and the Sangeet Natak Akademi fellowship in 2015 for stagecraft. He became friends with actor-playwright Habib Tanvir before the latter founded his Naya Theatre; they later parted ways. Theatre critcs see Dara Shikoh as a turning point in traditional theatrical sensibilities.

Sathyu left Delhi in 1962 and got a call from Chetan Anand again, asking him to join for his next film. Sathyu made his debut as art director with Haqeeqat (1964). The film, based on the India-China war of 1962, went on to earn him the Filmfare Best Art Direction award in 1965.

Sathyu is counted among filmmakers who, having made several good films, stand out for just one. In his case, it is his directorial debut film, Garm Hava (1973). He once said, “Can you imagine that our cinema did not make a single film on Partition for the first 25 years after it took place?” Garm Hava filled that gap, and how!

Some contest the claim that Garm Hava was the first Hindi film to look at Partition. Raj Kapoor's Aag (1948) mentions the traumatic event in a reference to the background of Nargis's character while ML Anand's Lahore (1949), Manmohan Desai's Chhalia (1960) and Yash Chopra's Dharmputra (1961) all had Partition as a backdrop. However, the fact remains that Garm Hava was the first significant film to focus entirely on the event.

Garm Hava was controversial from its inception, as it was the first film to deal with the human consequences of the Partition of India in 1947. This action, ordered by Lord Louis Mountbatten, the last viceroy of India, split the country into religious coalitions, with India remaining largely Hindu and the new country, Pakistan, serving as a refuge for Muslims.

But would ‘refuge’ be the right word for Muslims who did not wish to leave India? Would they ever be accepted socially and economically by the original residents of the territories of the newly formed Pakistan?

The film's protagonist, Salim Mirza, was portrayed by Balraj Sahni. Salim is a Muslim shoemaker and patriarch who does not want to relocate to Pakistan. There is the added element of a love story woven into this political narrative, and it is this element which adds greater meaning to the story impacted by Partition.

The filmmaker's imaginative use of light and framing added another dimension to the characters and their struggles. Salim finds himself vulnerable because of the forces unleashed by the shift in attitudes in the sensitive and volatile political environment, yet he refuses to cross over to the other side because he considers India his home.

Garm Hava remains one of the best films on how Partition victimized the minority and what impact it had on human lives, lifestyles, ideology and economics. The film received national and international acclaim and was nominated for the Golden Palm at Cannes. Sathyu says, however, that the greatest compliment came from the master filmmaker Satyajit Ray, who termed Garm Hava a trendsetter.

Garm Hava won several National awards in 1974, including one for National Integration. The film is routinely included in lists of best films, but its finely etched characters and deeply felt humanism have been largely hidden from public view since its theatrical release in 1974. Garm Hava was a personal milestone but also became something of a millstone for Sathyu. “When you hit a peak with your first film, everything else you do is compared to it,” he would say.

His Kannada film Kanneshwara Rama was produced by Moola Bhaktavatsala. Scripted by his wife Shama Zaidi, the Kannada dialogues were by Ramaswamy. The film was a success and ran for 50 days in Bangalore. The title role was essayed by Anant Nag.

The film is based on the novel Kannayya Rama written by SK Nadig. The story is set in the 1920s when a rebellious youth named Kanneshwara Rama opposes the unjust orders issued by the village head and is cast out.

His next film Bara (1982), remade as Sookha (1983) in Hindi, was based on a short story by UR Ananthamurthy with script and screenplay by Shama Zaidi. Bara was the first political film in Kannada and ran for 100 days in Bangalore. Sookha won the Filmfare Critics' award for Best Film and the National award for Best Feature Film on National Integration. Sathyu was conferred the Padma Shri in 1975.

Some of Sathyu's other notable works are Ek Tha Chhotu Ek Tha Motu (1967), a children's film, Black Mountain (1971), another children's film, and Galige (1994).

He has also been part of television through serials like Pratidhwani (1985), Antim Raja (1986, about the last king of Coorg), Choli Daaman (1987–88) and telefilms Ek Hadsa Char Pehlu, Thangam and Aangan. Yet, he remains one of the most grounded film personalities in India.

A few years ago, Sathyu startled everyone by doing an acting part in an advertisement for Google Search called Google Reunion which became a hit with viewers across the country. Since acting was something he abhorred except as director, when asked what made him accept the assignment, he simply smiled and said, “Money.”