Sholay offers a case study in how sound should always be synchronized with the entire film holistically and with the cast distinctively.

Sholay and the magic of Mangesh Desai's sound design – 45th anniversary special

Kolkata - 15 Aug 2020 23:57 IST

Updated : 16 Aug 2020 12:36 IST

Shoma A Chatterji

Ramesh Sippy's classic Sholay, which celebrates the 45th anniversary of its release today, is among the Indian films with the highest repeat value.

One reason for watching Sholay over and over again is that it offers a case study in how sound should always be synchronized with the entire film holistically and with the members of the cast distinctively.

Mangesh Desai, one of Indian cinema's legendary sound designers, had the rare gift of being able to creatively put together sound design, ambience, music and songs to offer the audience an emotional experience. Little wonder then that Sholay also became the first Indian film to market its soundtrack.

Sippy, his scriptwriters Salim Khan and Javed Akhtar, and sound designer Desai decided to invest each character of the film with a signature tune. The most outstanding among them is the eerie music that signals the presence of the dacoit Gabbar Singh, among the most important characters in the story.

The music was played on the cello by Basudev Chakravarty of RD Burman’s seventy-member orchestra. The music puts a kind of eerie spell on the viewer.

The title tune was played on the guitar by Kersi Lord and Bhupinder Singh which changes over to the French horn when the camera moves through the jungles.

The 'Yeh Dosti' number is composed against a whistling tune, creating the effect of youth, joy, camaraderie and freedom.

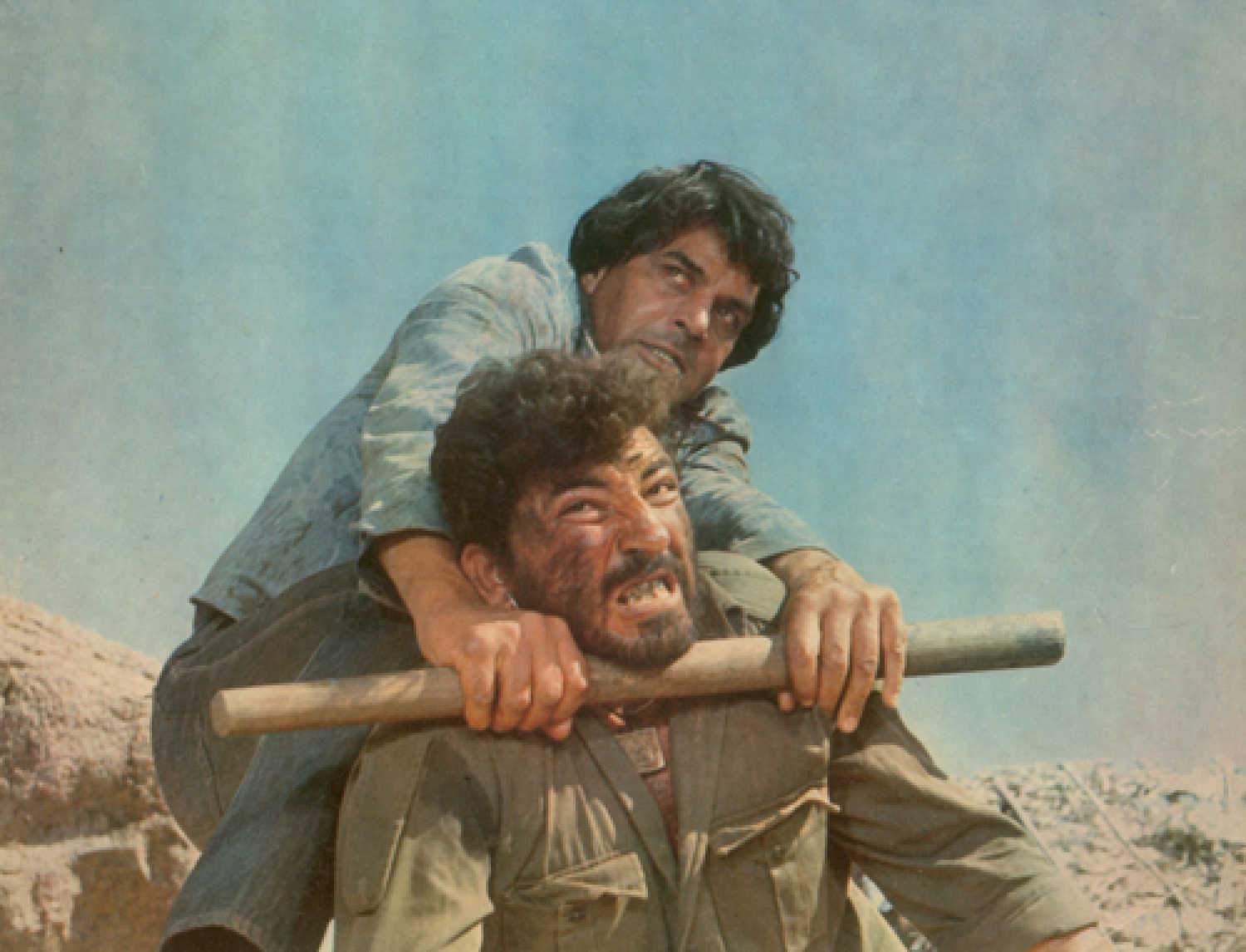

There is a beautifully shot and edited scene of armed men on horseback galloping parallel to the train when the bandits and Sanjeev Kumar's police officer and his captives Jai (Amitabh Bachchan) and Veeru (Dharmendra) are pitted against each other.

Towards the end of the film, the same sound motif of galloping hooves returns, this time with the dacoits chasing Basanti as she cracks her whip, yelling to her mare, “Chal, Dhanno, aaj teri Basanti ke izzat ka sawaal hai [Run, Dhanno, your Basanti's honour is at stake today]”, triggering and sustaining the suspense till it closes in Gabbar Singh's den.

The multiple layers of sound in this scene overlap and create a model lesson in sound design. One is the sound of the horses chasing Basanti's tonga. One is the sound of the bells tied around Dhanno’s neck that keep tinkling and creating an irony. And one is Basanti’s voice that keeps urging Dhanno on.

Desai actually imagined putting some of the sounds in the film in a specific way. For the coin-flipping scene, he suggested to director Sippy that the sound of the coin flying should reverberate in theatres. That effect was achieved by flipping a coin against a wall and letting it roll down a flight of steps during the sound mixing.

The flipping of the coin plays a dramatic role at the climax to decide who among the two friends — Jai or Veeru — should stay back to hold up the dacoits as the other rushes back to the village to get help.

Jai’s mouth organ is a symbol of his desire to be loved and to belong. Every night, he sits outside the outhouse of the Thakur’s villa and plays the harmonica, waiting for Radha, the Thakur's widowed daughter-in-law and the only member of the family to have fortuitously escaped Gabbar Singh's vengeance, to emerge on the balcony.

The tune Jai plays is the same every day, because that is probably the only tune he knows how to play. It is a melancholic tune that reflects the sadness of his life and the pathos underwritten in the solemn and silent face of the widow. It is also a silent pointer to the tragic end of this love story.

Basanti’s tonga is a motif of Basanti’s unusual characterization. The trotting sound of the mare pulling the tonga with Basanti cracking her whip from time to time is a sound metaphor that suggests the dynamic nature of her profession. She is a strong young woman, courageous enough to ferry male passengers from the nearest station to the village and back.

The sound of the tonga, overlapping with Basanti’s ceaseless jabbering and the bells that Dhanno wears plus the sound of her hooves are beautifully composed as these fade away into the horizon when she is taking Jai and Veeru to the Thakur’s house for the first time.

The sound design created during her climactic dance in Gabbar Singh’s den — to the moving song 'Jab Tak Hai Jaan' — intercut with the sound of bottles breaking all around her has the effect of watching a beautiful dance and being afraid of what is going to happen next at the same time.

Sholay has two main female characters — Basanti and Radha. Basanti runs a tonga service while Radha is a widow. Basanti is a beautiful extrovert, extremely talkative, one who just cannot keep her mouth shut. Radha is quiet, reserved, solemn, clothed in stark white widow's weeds, never smiling and never speaking unless absolutely necessary.

But, in a brief flashback, we find the same woman as a young maiden, playing with colour, jumping about, laughing away, and talking nineteen to the dozen. The sudden widowhood soon after marriage, the visible carnage of the entire family, shocks her into silence. Her present silence, juxtaposed against her talkative, exuberant past, underscores the burden life has imposed on her as a widow. Her voice has been sucked dry because, as the sole survivor in the carnage, along with her father-in-law, who, of course, loses his hands, she, perhaps, bears the additional burden of guilt. It is as if her self-imposed silence is a sort of life sentence she has inflicted on herself.

The Thakur himself is invested with a deep, gruff voice, but he prefers silence to speech in most of the scenes. It adds to the dignity of the character that keeps Jai and Veeru on their toes all the time.

Sippy and Salim-Javed took special pains to draw out different speech patterns to suit the different characters. Each character's personality is defined by his/her distinct manner of dialogue delivery, tone, voice, pitch and tagline.

The sound of speech and dialogue in Indian cinema is a highly subjective exercise. Sholay made it universal for the audience and exclusive to the film. For example, Salim-Javed sat down with Jagdeep to teach him how to speak in Bhopali Hindi which Jagdeep picked up skilfully enough to turn Soorma Bhopali into an archival character for all time.

Gabbar Singh's language is a mixture of Khariboli and Hindi. Khariboli is among several Central Indo-Aryan dialects spoken in and around Delhi. Gabbar Singh seemed to acquire a life and vocabulary of his own as Javed Akhtar wrote the character.

Asrani’s 15-minute presence with the tagline, “Hum angrezon ke zamaane ke jailor hain [I am a British-era jailor]”, as the English-affected jail superintendent in the film is another milestone. He spoke in a highly affected, Anglo-Indian brand of Hindi with a nasal twang to “hain” in the end that added to the humour of the character.

The other main characters spoke in ordinary Hindi so that the audience did not need to break its head to understand them.

Sippy also used several completely silent tracks to juxtapose them against the sound that happens all around. The blind imam's (AK Hangal’s) “Itna sannata kyon hai bhai [Why this silence of the graveyard]?” when everyone is gathered around the corpse of his son Ahmed (Sachin) and he walks in is one example. When Thakur Baldev Singh comes home on vacation to find the covered corpses of his family, the wind comes in to pull the covers away from all the corpses except his grandson's. The music fades into the background, subdued by the sound of the wind.

Resul Pookutty, who won an Oscar for his sound design on Slumdog Millionnaire (2008), has said, “Indian cinema is as aural as it is visual.” What better example can one offer than Sholay?