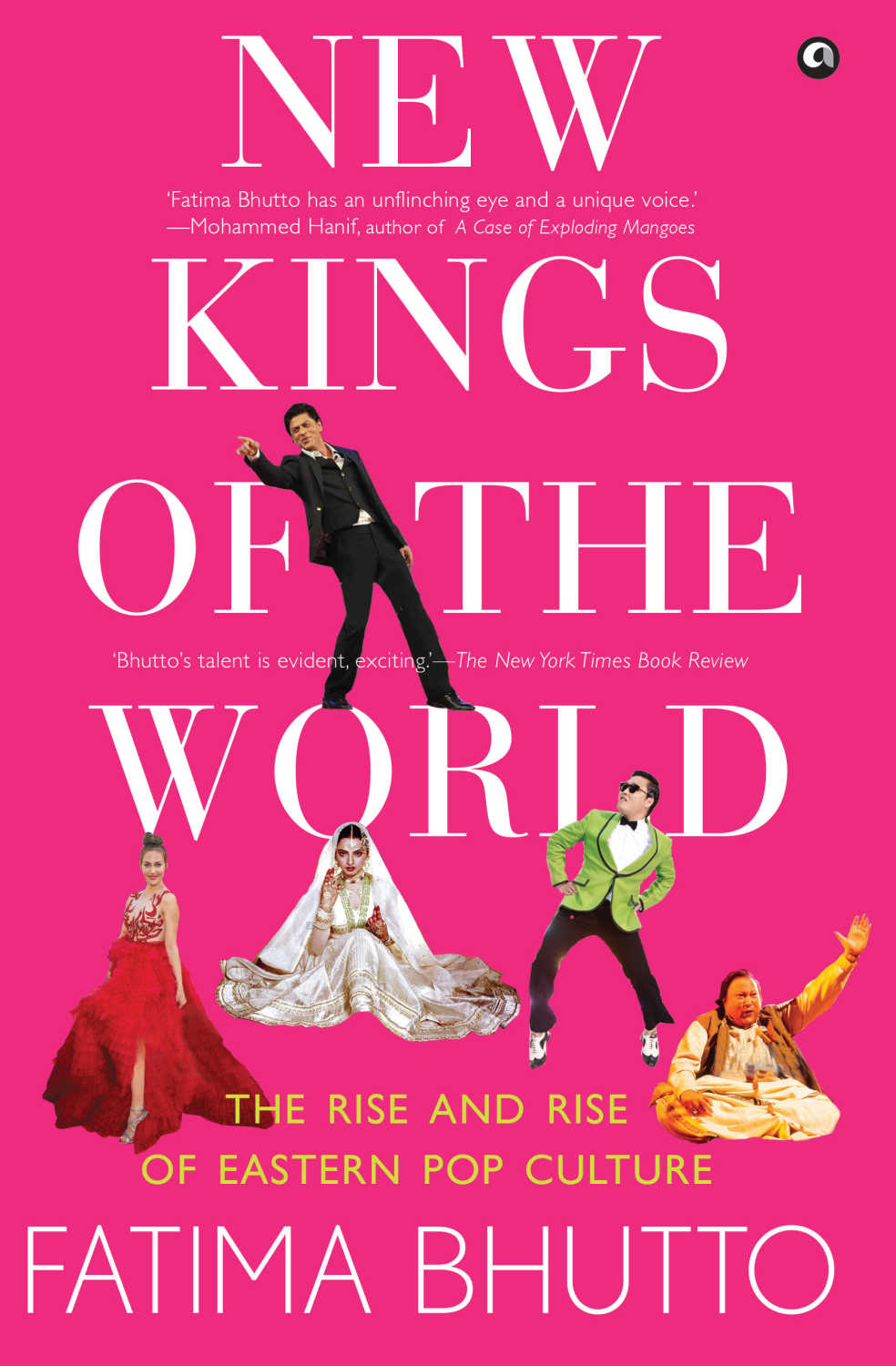

On former superstar Shah Rukh Khan's 54th birthday (2 November), a look at how he, Aamir and Salman Khan have reigned on Indian film screens since the 1990s, in an excerpt from the book New Kings of the World.

Book excerpt: What Shah Rukh Khan's characters understood that other heroes didn't

Mumbai - 02 Nov 2019 21:08 IST

Our Correspondent

When the country's secular foundations were seismically challenged, three stars appeared on cinema screens: Aamir Khan in 1988's Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak, Salman Khan in 1989's Maine Pyar Kiya and Shah Rukh Khan in 1992's Deewana. The three Khans were all born in 1965. At the time of their Bollywood breakout they were all in their early twenties. Aamir and Salman had influential fathers in the movie business, Shah Rukh did not. They were all educated, English-speaking, from comfortable if not well-off backgrounds, clean-cut and, interestingly, the three biggest actors in India all came from a community that makes up less than 15 per cent of the population: they were all Muslim.

The fact that the three Khans all rose in stardom at the same time is meaningful in the Indian and subcontinental context. In their earliest manifestations, the three Khans represented three prevailing spiritual and political ideas of India and the subcontinent. In this, Salman Khan's film persona was initially built on a defiant masculinity and a determined Muslim identity — though he may do love stories, you won't catch Salman being pushed around by a love interest. In Nizamuddin, the historic Muslim area of Delhi, it is Salman's face on the T-shirts of young men, not Aamir's or Shah Rukh's. Even as his politics, or lack of it, in real life is increasingly marked by timidity, in his heyday Salman Khan starred in films set on the Indian-Pakistani border where he takes in a Pakistani orphan or most audaciously plays an Indian RAW (or Research and Analysis Wing, India's intelligence agency) agent who falls in love with a Pakistani beauty who happens to spy for the ISI (or Inter Service Intelligence, RAW's Pakistani counterpart).

Aamir Khan is widely considered the intellectual of the three Khans and his films are lauded as probing and artistic. They also happen to be massive blockbusters. His 2016 film Dangal is the fifth most successful non-English film of all time and was a phenomenal hit from China to France. Aamir could be said to stand on the other end of the spectrum from Salman. He is Muslim, but never overtly so. Rather, he surrenders to the presiding energy and moment, largely accepting if not the values of the status quo, their dominance. Though in his personal life Aamir has criticized India's rising intolerance (while at the same time engaging in numerous Prime Ministerial photo-ops), in his films he doesn't engage in that fight. Aamir's films pointedly won't touch the politics of the time, but will focus on benign topics like dyslexia, general tolerance among mankind or women in sports.

While Aamir and Salman played heartthrobs in their first starring roles, Shah Rukh starred as homicidal maniacs and obsessive stalkers in three of his early movies, all blockbusters. In Baazigar, he asks a girl to marry him, makes her write a suicide note as a test of her love, and then pushes her off a building. After she dies, he adopts a new name, promptly asks her sister out, and ends the film by murdering her father. In Deewana he plays an awkward anti-hero romancing a woman who we think is a widow, but... and in Darr — "A violent love story" is the film's tagline — Khan plays a deranged, stuttering stalker. In the film he terrifies his love interest by calling her on the phone constantly ("I love you, K-K-K-Kiran"), breaking into her house, and shooting and stabbing her husband. Surprisingly, Indian audiences rooted for Khan's psychopathic character, not his frightened victim, enthusiastically cheering him all the way. "Pop sociologists," Pankaj Mishra noted, attributed Darr's success "to the growing 'anomie' in Indian society."

It is as though Khan's characters understood something other heroes didn't: this new world order accommodated, if not rewarded, violent confrontation. What mattered now was the hustle, how fast you rose, and how hard you fought your competitors. India had changed, and with it, the rules of the game in Bollywood. "He can die in the film and lose the girl," Khan later said of his creepy character trifecta. "He can kill people. We don't have to like him, just the story he is telling."

Excerpted from New Kings of the World: The Rise and Rise of Eastern Pop Culture by Fatima Bhutto with permission from Aleph Book Company. Click here to buy a copy of the book.