Mrinal Sen, the great filmmaker whose mortal remains were consigned to flames on New Year's Day, was a jolly man full of anecdotes and a never-ending quest for learning.

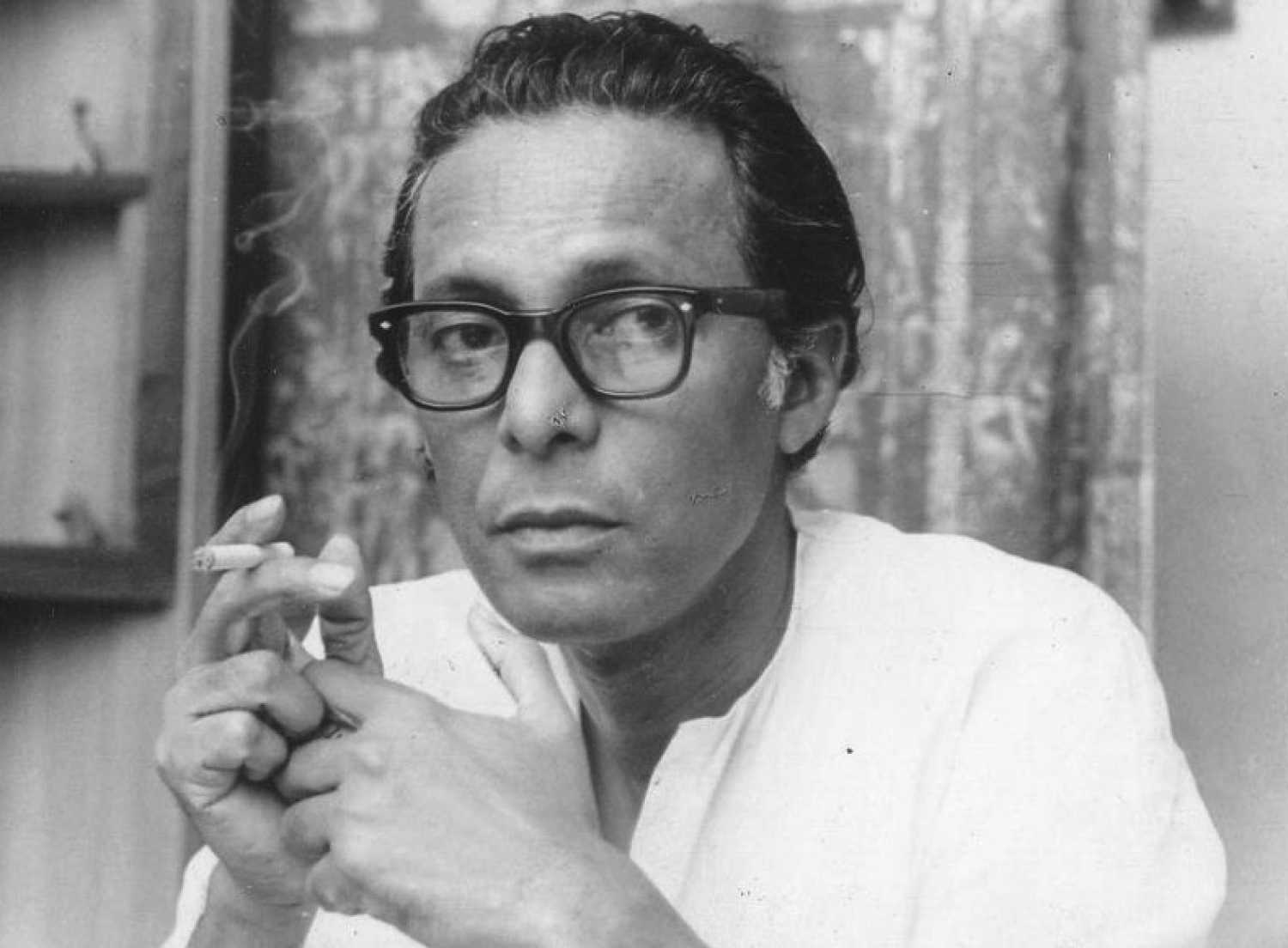

Tribute: Mrinal Sen, the great filmmaker who never lost touch with reality or his three 'mistresses'

Kolkata - 03 Jan 2019 18:36 IST

Shoma A Chatterji

Mrinal Sen, who passed away on 30 December 2018 at his residence in Padmapukur, Bhawanipore, Kolkata, was a man who blurred the difference between the personal and the professional with great ease.

It was his nature, his habit. He did not feel the need to keep a distance between himself, a celebrity, and the man on the street. For many years, he would open the door to his flat himself, or his relative Anup Kumar, the noted Bengali actor who almost lived with the Sens, would.

With the growth of the electronic media, Internet and e-mail, Mrinalda taught himself to use e-mail and sent me a brief note thanking me for a positive review of his last film Aamaar Bhuvan (2002), when I reviewed it for a national daily. I was surprised because not many people of his age and status would deign to correspond with a small-time journalist like yours truly, that too, through e-mail.

This was Mrinalda’s greatest gift — the art of remaining rooted to his identity minus that imaginary halo he could easily have worn around his head.

Mrinal Sen: The filmmaker as ideologue

I have interviewed Mrinal Sen several times since 1971, when I was just beginning my career and he was shooting Calcutta ’71, till his last film Aamaar Bhuvan. Among the filmmakers I have interviewed over the past 40 years, I have interviewed him the most number of times. I have grown with his films and along with him. In some unconscious way, he played an important role in shaping in me the importance of values like modesty, and taught me that the quest for learning is infinite.

He was an extremely anecdotal man, filling his interviews with tales that transcended the borders of subject, history and geography, age, status and gender.

I wrote a brief biography of Mrinal Sen under the commission of Rupa Books some years ago. The book hardly did justice to this monumental man because I had to keep the content limited to about 10,000 words. I dreamt of doing a bigger book, but before that, over the years, much better books on him than I could have ever written were authored by noted people like journalist Shiladitya Sen and ex-bureaucrat Dipankar Mukhopadhyay.

For every single interview I did with him, he would go off at a tangent and it would be impossible to hold him down to my carefully constructed questionnaire. Precisely because of this habit of his, I came away a much better informed person about life in general and cinema in particular, with anecdotes from his life in cinema and, sometimes, out of it.

Mrinal Sen was the critical insider; he wasn't attached even to his own work: Son Kunal

When I visited his Beltala Road flat on my 60th birthday to touch his feet to seek his blessings — he did not allow anyone to touch his feet, but my birthday, I guessed, would be different — he asked how old I was. When I told him, he laughed and said, “Now I cannot even make love to you!”

I was still to get used to his jokes and so was visibly shocked till he began a long treatise on his friendship with MF Husain and his own stand on Gaja Gamini (2000) followed by Meenaxi: Tale Of 3 Cities (2004).

He said Husain had sent him two air tickets to attend the premiere of Gaja Gamini in Mumbai with hotel stay included. Mrinalda saw the film and though he agreed that he could not understand much of what was happening, he was fascinated by the late painter’s sense and use of colour as a strategy and a film language.

Few people knew that the first person to give the great Amitabh Bachhan a 'voice-break' was none other than Mrinal Sen. "I was in Bombay for the post-production work of Bhuvan Shome when [Khwaja Ahmad] Abbas was preparing to shoot Saat Hindustani (1969). My film featuring newcomers needed a good Hindi-speaking male voice for a commentary to be used as a framing device. I approached Abbas because I knew he, too, was working with a group of rank newcomers for his forthcoming film. I found him surrounded by these seven youngsters who would be debuting in Saat Hindustani. One of the boys, a lanky, dark and very tall youngster, ventured forth, speaking to me in very bad Bengali. But I liked the feel of his voice and took him with me. That was Amitabh Bachchan. At first, he refused to accept payment for his work. But I insisted and he did accept,” said Mrinalda, pulling out one anecdote from his huge library of reminiscences.

Amitabh Bachchan turns 75: He had no time to feel shy, says Saat Hindustani co-star

Between 1956 and 2002, Mrinal Sen made 28 full-length feature films, a couple of documentaries and two television serials. His feature films were mainly in his mother tongue, Bengali, though he also made films in Hindi, one in Telugu and one in Oriya.

Sen is one director who made films in languages he did not know, like Oriya and Hindi, at a time when Bengali directors were fiercely parochial against making films in any language other than Bengali.

Sen did not believe in an exclusive linguistic identity as a filmmaker. "I am against this Bengali chauvinism of making films in Bengali alone," he said. "This narrowness closes us to the rest of the world. Besides, it is not as difficult to make a film in an unknown Indian language as people generally make out. Regional peculiarities are always there, in the shape of physiognomy, food habits, dress styles, dialects, words, etc. If one can grasp these properly, which is not difficult for any Indian, one can easily make a film in the language of any Indian region. Granted that it is easier for me to make a film in Bengali than in another language. But that in itself evolves into a challenge which I love to meet."

Topicality was a strong point with Mrinal Sen ever since he made Akash Kusum (1965) which led to a historic press debate between him and Satyajit Ray. But he was equally fond of literature, both classic (he made a Telugu film based on Premchand's famous short story Kafan) and contemporary. His Ek Din Achanak (1989) was based on a novelette by Ramapada Choudhury.

Sen liked to "redefine or reinterpret a story in the context of the present-day situation. To do this, I do not traverse the physical aspects of the story. For example, if I were to make a film on the character of Rama from the Ramayana, I will treat him like an imbecile who made his wife prove her chastity so that he could wear the crown and become king. Allegiance to the time I live and work in is very important to me. When I make a film based on a literary piece of work, I know I have to serve three mistresses at the same time — the story written at a particular point of time, its placing within the medium of cinema, which has its own artistic conventions depending on the two physical properties of light and sound, and, of course, my own time. While serving these three mistresses, I also feel that it is perfectly within my rights to be critical of the story I am making into a film."

I was surprised to meet him at a British Council release of Satyajit Ray: A Vision of Cinema to celebrate the golden jubilee of Pather Panchali (1955). Other filmmakers, contemporary and junior to Ray, were conspicuous by their absence at such a prestigious event.

Satyajit Ray and his equations with contemporary Bengali filmmakers – Birth anniversary special

“How could you even ask me such a question?" he responded. "I just have to be present because he has made a landmark film for all time and we are celebrating 50 years of his milestone film Pather Panchali.” That was Mrinalda, free of envy and appreciative of one of his arch rivals in filmmaking.

Sen’s films have journeyed thematically from contemporary social and political crises to an examination of the inner journeys of individuals. Moving from formal dramaturgy to non-narrative searing statements to some searching self-analysis, the filmmaker tried to sustain a balance among his commitment to (a) the story placed in a particular time setting, (b) his medium, cinema, to which he owed his ideological obligations and (c) his time, which “sits on my neck”. These were, in his words, the ‘three mistresses’ he had been serving.

Young cinematographer Aveek Mukherjee found it challenging to shoot Aamaar Bhuvan, Mrinalda’s last film, in an ambience where electric light was not to be used in a single shot.

"I used Kodak Expression film because it can capture many shades of black," Mukherjee recalled. "I was a bit apprehensive about working with a senior filmmaker like Mrinalda. But it turned out to be a delightful experience. He arrived on the sets much before others did. He directed me about what lighting he wanted, where and why. The casual air of bonhomie on the sets aided by his ready stock of anecdotes made it a once-in-a-lifetime experience.”

Asked once what he would like to be in his next birth, Mrinal Sen said: "Ek Din Achanak unfolded the story of an ageing man who walks out of his house on a rainy night and never comes back. When his wife and three adult children try to find out why, they discover among the debris of his scribbling a single sentence: the saddest part of life is that you only live once. I wish I could start my life from scratch so that I can correct the mistakes I made in this life and re-live a better life. But is this possible?"

Today, it is not. Bye Mrinalda. You will live on in our hearts with your jolly camaraderie and your album of some memorable and wonderful films forever.