Set against the Muzzafarnagar riots that shook India in 2013, Ek Betuke Aadmi Ki Afrah Raatein is a tale of alienation of a man and his surroundings in a communally tense state.

Drew on Dostoevsky's Dream Of A Ridiculous Man, White Nights: Sharad Raj on Ek Betuke Aadmi Ki Afrah Raatein

New Delhi - 23 Jan 2019 13:00 IST

Ramna Walia

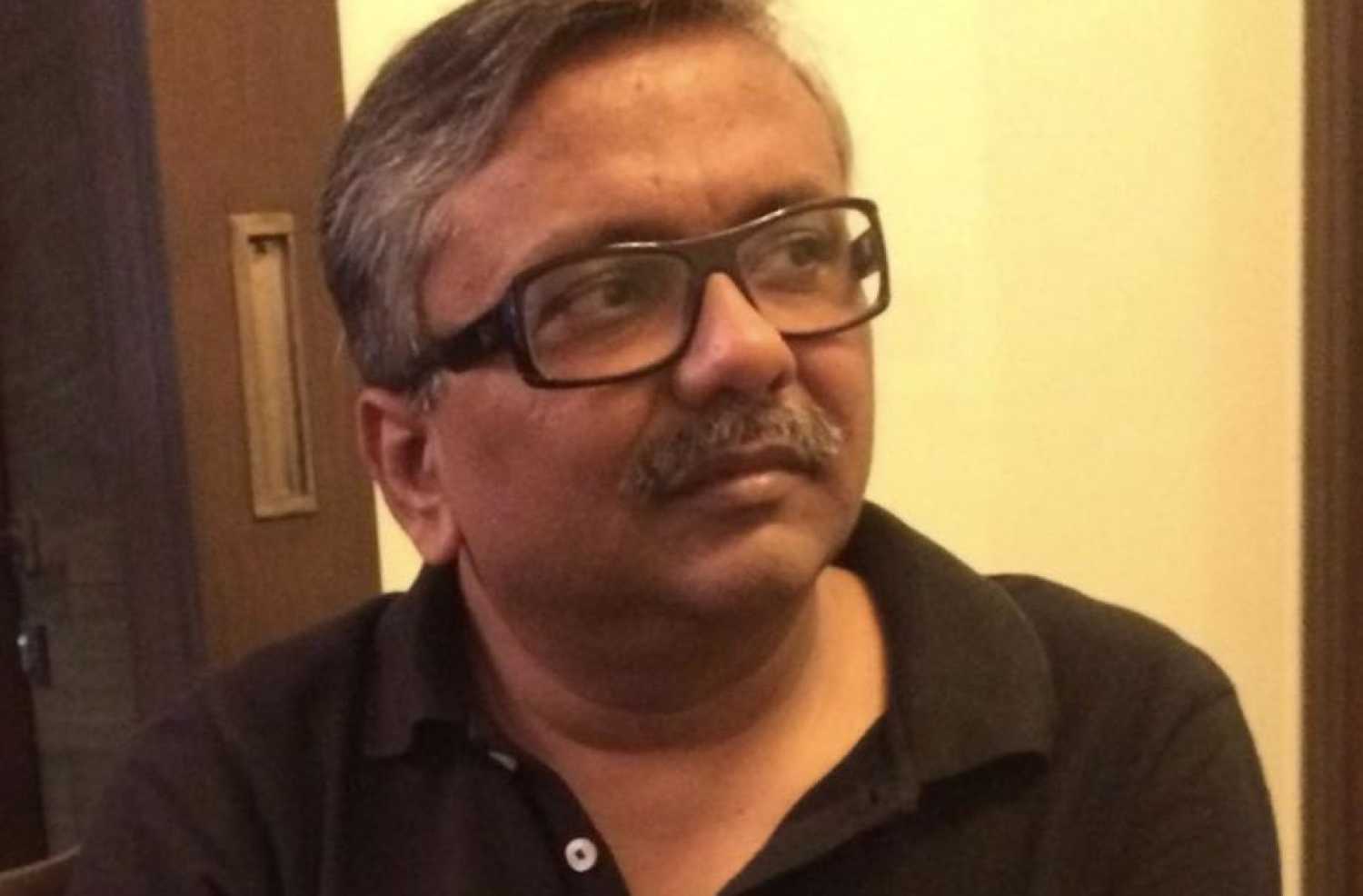

Independent cinema continues to thrive in the festival circuit. Independent filmmaker and Film and Television Institute of India (FTII) alumnus, Sharad Raj joined the Diorama International Film Festival & Market (DIFF) with his film, Ek Betuke Aadmi Ki Afrah Raatein, for the film bazaar section of the festival.

Set against the Muzzafarnagar riots that shook India in 2013, Ek Betuke Aadmi Ki Afrah Raatein is a tale of alienation of a man and his surroundings in a communally tense state.

Sharad Raj draws on Russian writer, Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Dream Of A Ridiculous Man and White Nights and uses abstract juxtapositions and social realism to convey deterioration of the self in a toxic socio-political background.

Cinestaan.com caught up Sharad Raj on the sidelines of the festival. Excerpts from the interview are below:

How did this film come about? What prompted you to make this film?

A couple of things on that front. In 2014, I was as disturbed as most people are in the country. I am not surprised by what is happening in our country right now. I, like many others, could see this coming. That disturbed me a lot. The Muzzafarnagar riots had happened in my home state and they were single-handedly responsible for bringing this government to power since 72 seats in Uttar Pradesh is a sure shot key to the Parliament. So the film is born out of this socio-political atmosphere.

I’ll also say that this political tension is not new. Any country is divided along the communal lines has a problematic history. On top of that we have new anxieties of globalization.

So for me, response to this kind of social order, as an artiste, had to be aesthetic. One can choose this as a subject matter and dramatize it. For me, that’s not enough. I don’t think it helps except sensationalize the reality. So for me, the response had to be at a formal level. I had to reinterpret the form or my response would have been half-baked. I had to marry form to my response rather than a more traditional plot-driven route. I drew on Dostoevsky's Dream Of A Ridiculous Man and White Nights. These stories have been with me since the last 20 years or so.

Inspired by the writings, I wanted to explore the quotient of guilt in modern times [which] would be substantially more especially in a situation of the riot. I changed the betrayal from the personal to the political scenario. The only way I could truly explore this is through love. For me, love is god and it is our only hope so I drew on the love story of White Nights. I wanted to explore sacrifice, not in the sense of fighting at the border or laying one’s life, but as a human connection. So this instinct drove me immensely.

The formal choices you speak of is evident in the way in which your film draws on various texts — you mentioned Dostoevsky, but you also draw on poetry, documentary, art. How do you think these shape your sensibility as a filmmaker?

Being a part of FTII, I had a few obvious influences. One was Resnais’s Hiroshima Mon Amour which also uses documentary footage of the bombing. The second influence is Andrei Tarkovsky and his meditation on the job of an artist as an observer of time. The long takes and the poetry to that end is something that I draw on from Tarkovsky. And the third influence on me is Ritwik Ghatak. His preoccupation with mythology and Jungian collective and the individual. You see this struggle between the individual and the collective in the film. I also draw on the epic structure that Ghatak often follows.

Mixing all these creates a mosaic or a tapestry of the world that we live in. It’s a world that has desensitized us completely. Mass media has played a huge role in this. Another culprit is bad popular culture. I have nothing against popular culture. I love Hitchcock and Manmohan Desai. But all of this needed to be contextualized into my story.

In the film, you don’t see the process of alienation, the characters, at the very outset, are alienated. It speaks to the times they belong to. It is hard to capture this through narrative form. This cohesive, middle-class approach to narrative cinema needs to be countered. And I am here to fight it out with this non-narrative epic structure.

What do you think is the space of stories like these and for independent film like yours today?

It’s very difficult. Even film festivals have their own formula. It is a very tough journey. The point is not selling it. Luckily for me, a major chunk of the film is crowd-funded. There are other concerns with say, Netflix. What if the censorship rules change, or there is a greater state interference on content? I have made the film I wanted to make. I want to take it to a discernable audience or for people to whom cinema interests as an art form. Film festivals have played a role in providing filmmakers like me that audience. Today, whether it is through a festival or a digital platform like Netflix, I want to reach that audience.

Related topics

Diorama