Bandini was the first Hindi film to depict the story of a woman imprisoned for a murder that she committed and confessed to without pleading for forgiveness or harbouring any sense of guilt.

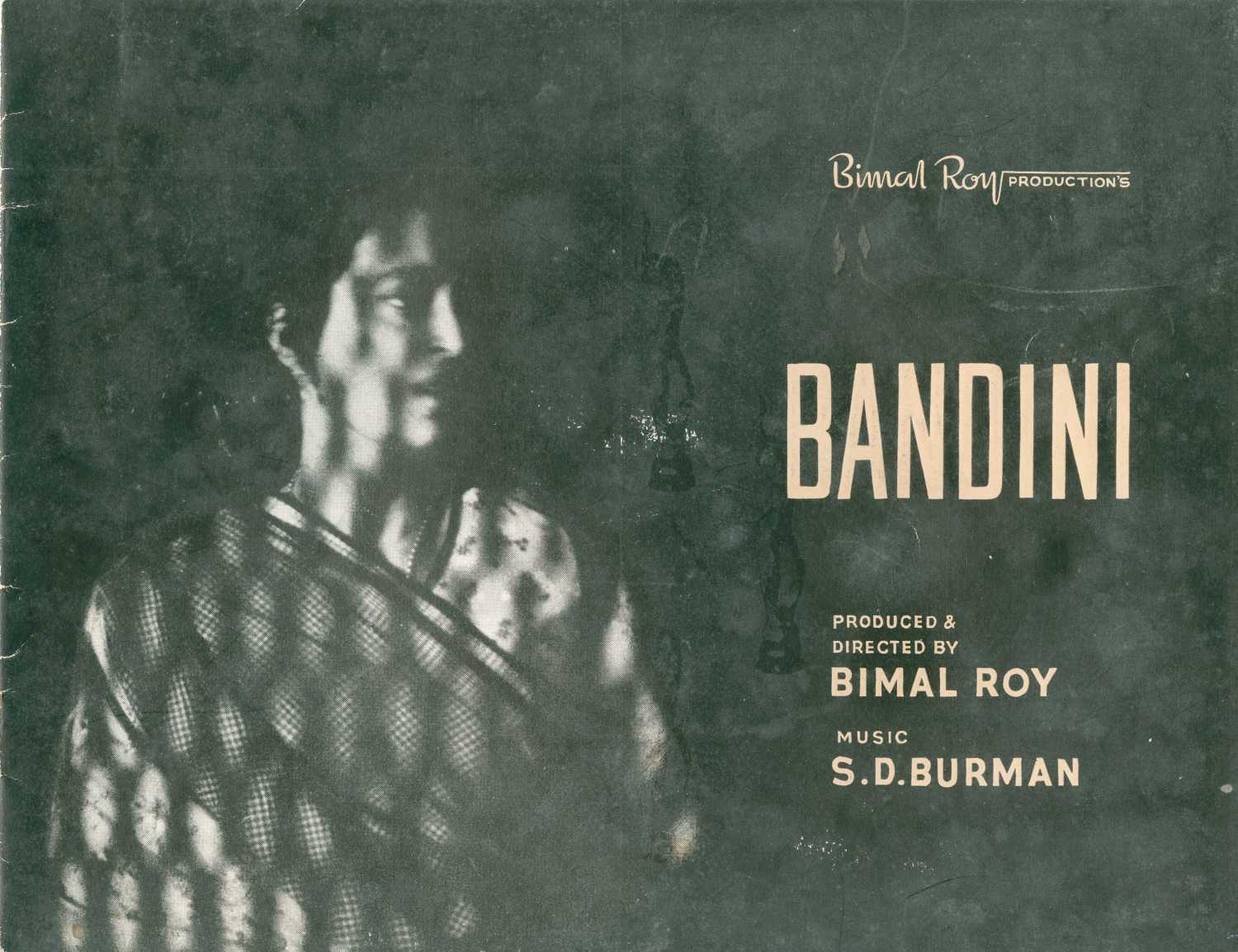

Revisiting Bandini: Bimal Roy's most complete film with Hindi cinema's first independent woman

Kolkata - 01 Jan 2019 7:00 IST

Shoma A Chatterji

Bandini was released on 1 January 1963 at Bombay’s Royal Opera House in a star-studded premiere. This writer, a teenager then, had the good fortune to be present at the premiere, mainly to gawk at the stars making it to the venue.

Bandini remains a classic. The film was set in pre-Independence India with discontent brewing among groups of people that leads to some revolutionaries being forced to go underground for fear of being imprisoned by the British.

Bandini, or The Prisoner, was the first Hindi film to depict the story of a woman imprisoned for a murder that she committed and confessed to without pleading for forgiveness or harbouring any sense of guilt. The story is told mostly in flashback from the protagonist Kalyani’s point of view.

Bimal Roy used imagery and sound beautifully to convey the changing and sometimes volatile moods of Kalyani, enacted by Nutan in what is arguably the most powerful performance of her career.

One noticeable change Bimal Roy made in the film was to change the name of the original character of the prisoner from Hena to Kalyani. Kalyani, derived from 'kalyan', meaning 'welfare', is turned into an adjective in Kalyani that defines a woman who is born to work for the welfare of others.

Kalyani, an inmate of the women's ward of a prison in British India, is determined to serve out her full term. She resists the subtle but strong overtures of the prison doctor, Deven (Dharmendra), who wants to marry her. She fears for him because of her scarred past. She is determined to sustain the status difference between herself and Deven and believes her presence in his life will destroy his future because of the social stigma she carries.

Kalyani writes her story in a notebook for Deven and the film cuts back to some village in the 1930s. As the motherless daughter of the village postmaster (Raja Paranjpe), Kalyani gets emotionally involved with Bikash Ghosh (Ashok Kumar), a political activist in hiding, an anarchist always on the run from the British police.

Once, Bikash falls sick and while tending to him Kalyani falls asleep and spends the night in his room. To rescue her from scandal, Bikash tells everyone Kalyani is his wife. Before leaving the village, he promises Kalyani’s father that he will come back and marry his daughter formally. But he never does.

The father and daughter are targets of ridicule and become social outcasts, forcing Kalyani to run away one night to save her father from further humiliation. As she runs away, the soundtrack fills with a beautiful situational song by Mukesh: "O jaanewale ho sake toh laut ke aana [Thou who depart, do return if you can]."

Kalyani takes up the job of an ayah in the women’s ward of a hospital in a city. A particular patient, a neurotic woman, makes life difficult for her. One evening, when the patient’s husband is visiting, Kalyani is made the butt of her insults. Kalyani discovers that this is the woman whom Bikash married, leaving her in the lurch. The same night, a telephone call informs her of her father’s sudden death in an accident.

These three incidents, piled one upon the other, disturb Kalyani deeply. Later that night, she poisons the woman, not in a fit of rage but as if in a trance-like state, consequent upon seeing her father’s inert corpse on the hospital bed.

The diary only strengthens Deven’s resolve to marry Kalyani. His mother is prepared to accept her. As Kalyani waits for the train to take her to Deven’s home, she runs into the terminally ill Bikash, waiting for the steamer on the other side of the matted wall of the waiting room. The young man escorting Bikash tells her Bikash’s marriage was part of his commitment to his revolutionary group and he was forced to marry the neurotic woman.

As the steamer begins hooting to announce departure, Kalyani rushes up the shaky wooden plank to join Bikash with SD Burman belting out the song 'O Re Manjhi' — "Mere saajan hain uss paar, main man maar, hun iss paar, o mere manjhi abki baar, le chal paar. [My love is on the other shore, I, who had killed all desires, am here, O dear boatman do take me across this time]."

The lines, mai bandini piya ki, mai sangini hun saajan ki, sum up Kalyani's story. She has been a prisoner of love throughout life and the physical reality of her imprisonment was but a symbolic representation of this love, her landing behind bars for murder being traced back to her betrayal in love.

The imaginative and aesthetic use of sound and imagery through black-and-white frames to express the loneliness, sense of alienation, and acceptance of her condition that Kalyani experiences within the prison is unforgettable. Standing all alone in a corner of the jail compound facing the prison's high wall, she can hear the hooves of the horse on the soundtrack pulling the carriage carrying Deven away.

Before she poisons Bikash’s wife, Kalyani sits with her back to a grilled window, her face in relief against backlighting, the sounds of a welder working in the neighbourhood hammering nails of noise into the sinister ambience of the evening. Her hands tremble as she pours the poison from the bottle, but her eyes burn with the determination of the terrible deed she has decided to carry out.

Perhaps, considering this was a hospital, the sounds and sparks from the welder were symbolic of Kalyani’s mental state of shock and trauma and may not have existed in physical terms. Her dark face is framed by the backlight from the sparks and flashes, real or imagined. Her face is only dimly visible.

Kalyani pumping the pressure stove to make tea, the sound of the lit stove, Kalyani happening to overhear a conversation between the woman and her husband, the woman throwing away the cup and saucer while screaming at Kalyani, Kalyani’s silence juxtaposed against the irritating and eccentric outpourings of the sick woman, the cleaning woman letting out a crazy scream when the murder is discovered, are some examples of ambient sound.

The murder, unfolded in flashback, is committed in the nursing home where the victim is admitted as a mental patient and where Kalyani works. The night before the murder, Kalyani is shown seething with cold anger at the repeated insults by this patient.

The murder is discovered the following morning. Incidents building up towards the murder are carefully set up to establish her psyche. The friend, whose husband had helped her get the job in the hospital, calls up to inform her that her father has met with an accident. Kalyani rushes out. When she reaches the hospital, her father is dead. She walks back, silent. The recalcitrant patient screams at her.

Every frame in the film is carefully designed, spilling over with layers of meaning. Kalyani and Deven are constantly shown together in their early meetings without any barrier between them. But when Deven proposes, we see a door between them. Kalyani turns down his proposal without having to look at him. The door could be read as a signifier of the barrier Kalyani feels exists between the honest, respectable, kind and committed prison doctor and herself, a murderess.

After this scene, the two are always shown from two sides of a given space with a barrier between them. If he is outside the room, she is inside and he sees her through the bars of the window.

From Kalyani’s point of view, she sees him standing outside through the bars of her cell window. The final point of separation comes when she does not see him at all but hears the sounds of the horse’s hooves and the rolling wheels of the carriage.

The call of the prison guard announcing "sab theek hai [all is well]" spells out just the opposite: nothing is fine. This brings out the irony behind the walls of a prison where prisoners, stripped of their identity, are mere numbers; where life is reduced to an eternity of waiting either to go out to an unkind world that will not accept them or to die inside.

The prison guard’s call is used three times in the film. The first time, we see a freedom fighter taken into the prison. The second time, Deven has resigned and is going back home. The last time the guard calls out sab theek hai a freedom fighter has been taken to the gallows.

The calls function as subtle and underplayed counterpoints in the film. The song, 'Mat ro mata, laal tere bahutere [Don't cry, mother, many are your sons]' as the freedom fighter is marched to the gallows with his family crying outside the prison gates appears a bit melodramatic in retrospect because it does not belong.

Bimal Roy uses the spaces within the jail compound and the bars of the prison as powerful symbols depicting openness and imprisonment. They represent the seclusion of the prisoners, separating them from others and imprisoning them within their hold. The open spaces within the prison are seemingly enclosed but they offer respite for Kalyani to think, to introspect and, in some ways, to create a distance between herself and the other prisoners.

The other women prisoners are placed in these spaces to do their chores — grinding wheat on a big grindstone, singing songs that carry resonances of the homes they have left behind, getting into fights and taking rude pot-shots at the jail officer’s generosity towards Kalyani. One can see the flowering of spring from behind the bars that signifies the passage of time and the lack of change in the lives of the inmates.

The bars symbolize Kalyani’s quiet acceptance of her life in prison. When one of the woman prisoners is diagnosed with TB, she steps forward to nurse her. When there is an appeal for early release, Kalyani puts her foot down. When the jail doctor adds an egg to her menu because she needs nourishment for nursing a TB patient, she refuses. It is as if she does not mind remaining a prisoner forever.

The murder was committed on the spur of the moment out of a sense of deep rage, frustration, grief and revenge. But she feels guiltier for her father’s death than for the murder she has committed. The script remains quiet about her feelings of guilt.

Nutan communicates with her eyes and hardly speaks. She underplays the character, fleshing Kalyani out as a quiet but determined woman with a dignity that belies her prison backdrop. Her mental state is expressed through a flood of fleeting emotions, especially in the scenes leading up to the murder and afterwards. When the body is discovered the next morning, she pulls her hair, her sari falling off her chest, screaming out that she is the one who has killed the woman.

Bandini makes no attempt to iconize or justify the character of Kalyani. Nor does it make her a martyr to any cause. Kalyani does not have any agenda — individual, social or collective. She is an ordinary woman placed in a crisis over which she has no control. The film makes no effort to clear her of her crimei.

Bimal Roy’s love of realism is reflected in the gentle fleshing out of all the characters in the film. Be it the gentle but firm Kalyani, the two men in her life, the middle-aged female warden who looks after the women’s ward, Kalyani’s gentle father who is a postmaster but very spiritual, the sympathetic jailor, the slightly villainous deputy, the other women prisoners, Deven’s mother who surrenders to her son’s wish to marry a woman jailed for murder emerge as real people. Kalyani’s friend and her husband who help her to get the hospital job and then inform her of her father’s accident are gentle, sympathetic, ordinary individuals, and are not judgemental.

The use of bars, grills, walls, barbed wire and other barriers is representative of physical distance. Bimal Roy uses these barriers to show the physical as well as mental confinement of characters. Such barriers are also used as a foreshadowing technique, symbolic of what is to comeii.

Kalyani's character has two facets. One is Kalyani as a prisoner within the prison walls, sometimes shown in long shots, sitting in front of the formidable wall, like a tiny, vulnerable cog in a large wheel — firm, silent, serious, unapologetic and unsmiling.

The other dimension comes across in the flashbacks in her village home, coy, feminine, wearing coloured saris, her forehead dotted with a small bindi surrounded by a circle of tiny dots, smiling a lot, talking some and singing songs while fetching water from the nearby river, dedicated to the love of Krishna and Radha. She shares a strong bond with her father, educated in the Vaishnava scriptures, their influence reflected in the songs 'Mora Gora Ang Lai Le' and 'Jogi Jabse Tu Aaya Mere Dwaare'. The change in her character, approach, attitude and language after she leaves her village home reflects a woman trapped in an unforgiving world.

Kalyani is one of Hindi cinema’s first women to live life on her terms and not compromise with social and filial pressures. She is feminine, soft and gentle, even apparently submissive. But beneath this soft exterior lies a mind of steel that can make decisions even at critical moments and throw away the certainty of a secure future. She willingly throws her life away by surrendering to her emotions and offers succour to the only man she has ever loved, now dying.

Bandini was Bimal Roy's most complete film. It depicted the 'complete' woman with an appeal that transcends the personal to enter the political, a significance that is more universal than individual.

References:

i Ziya-Us-Salam, Bandini, The Hindu dated 1 October 2009

ii Maitreyee Mishra and Manisha Mishra, The Outsiders: Women as Social Outcasts in Bimal Roy’s Films. Paper presented at International Conference on Communication, Media, Technology and Change, 9-11 May 2012, Istanbul, Turkey.