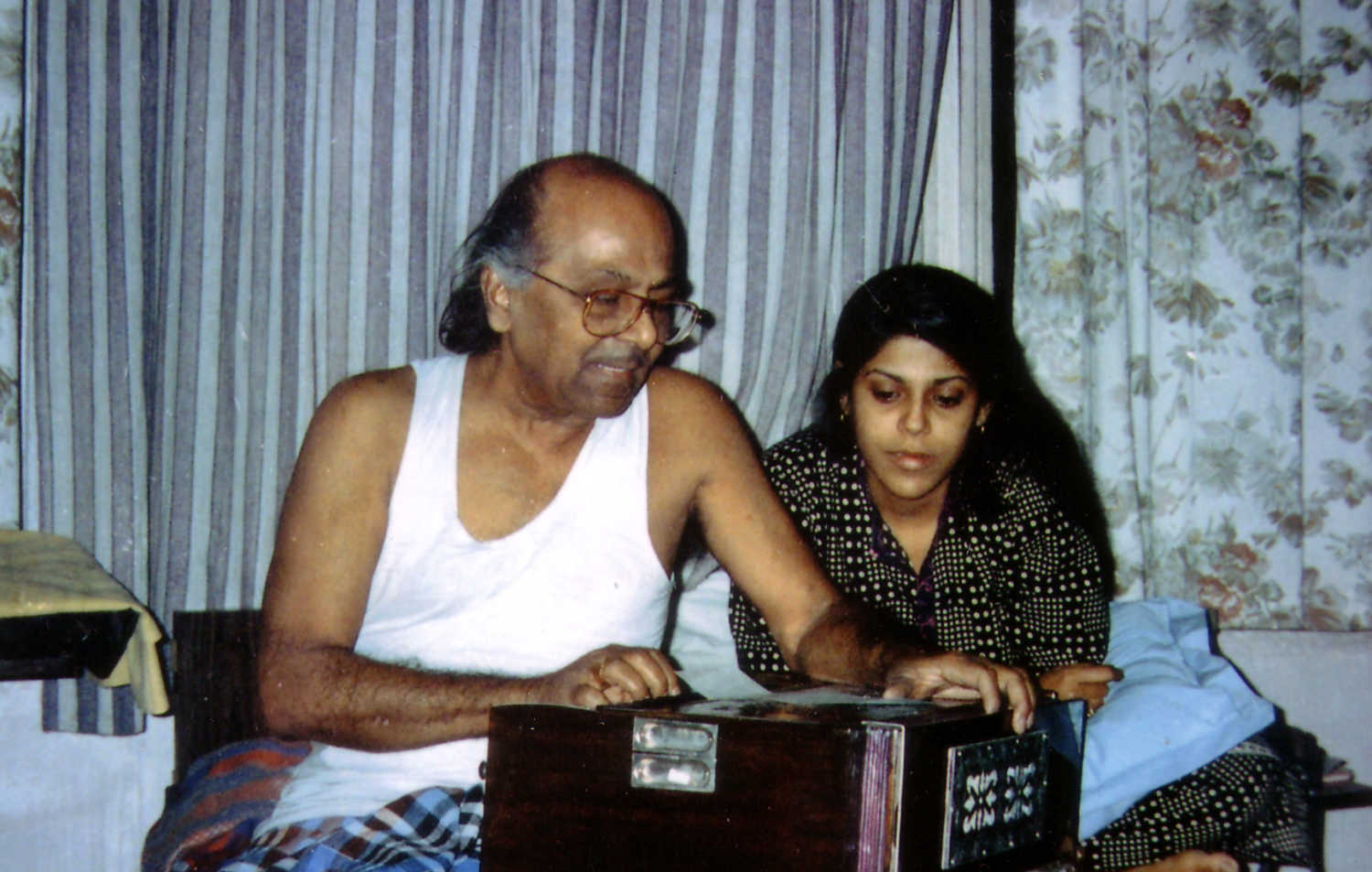

On the great lyricist-composer's 23rd death anniversary (Salil Chowdhury died on 5 September 1995), daughter Antara recalls his ouevre and his lessons.

No alternative to sadhana, however talented you may be: Salil Chowdhury's advice to his daughter

Kolkata - 05 Sep 2018 15:49 IST

Roushni Sarkar

Salil Chowdhury made immense contributions to Indian cinema, not just as one of the finest, pioneering and experimental music directors, but also as a poet, a lyricist and an activist of the early Socialist movement in the country.

Chowdhury introduced new rhythms, Western orchestration and harmony, and electronic elements in Indian music to make it richer while his words often instigated the fire of patriotism and touched upon the various shades of the universal language of love.

On Salil Chowdhury's 23rd death anniversary today (he passed into the ages on 5 September 1995), Cinestaan.com spoke to his daughter Antara, one of the more talented singers and composers of this generation.

As Antara Chowdhury, drenched in emotion, shared memories of her father, she reflected that her soul is connected to her father, his works and his ideology. She inaugurated the Salil Chowdhury Foundation of Music, Social Health and Education Trust in 2002 which aims to preserve his works.

She, along with her fellow trustees, plans to arrange a special screening of Pinjre Ke Panchhi (1966), a film directed by Chowdhury, on his birthday (19 November) this year. The trust also gives free music lessons and instruments in his name.

Antara Chowdhury inaugurated a school called Suradhwani last year and teaches the songs composed by her father there. She wishes to extend the school further with more involvement from artistes.

Excerpts from a conversation with Antara Chowdhury:

Your father was never interested solely in exploring his own music. He always spoke of the improvement of Indian music.

Yes, Baba had many dreams as you have heard him expressing them in many interviews and shows on television. Baba was not only a musician; he was also an intellectual. He was always concerned about the advancement of Indian music. At the same time, he showed how, with the help of Western harmony and techniques, the melody of Indian music can be retained and improved. He used to study a lot; we have a lot of books in our home on those subjects.

Baba also had a dream of introducing a course on music composition so that new composers can receive training and build their careers. Unfortunately, it never materialized for lack of infrastructure, funds and support from the government. However, I am hopeful for such a project in the near future.

How do you remember him enriching himself with the knowledge of Indian classical, Western and folk music?

He used to listen to music of diverse kinds all the time. In our home, some music — whether it was Indian classical or Western or folk — was always being played. Whenever he was in foreign countries, he was on the lookout for the folk music of those regions. In fact, he used to travel to many corners of our country also to search for the music of the roots. It was my father’s passion.

Baba grew up on a tea estate in Assam and was quite inspired by the songs and the music of the coolies there. For example, the influence of Bihu songs can be found in 'Chadh Gayo Papi Bichhua' from Madhumati (1958). 'Uthali Pathali Amar Buk' from Ganga (1961) was inspired by Bhatiali from Bangladesh and West Bengal. It can be easily understood if you closely analyse the songs.

Baba himself used to talk about the inspirations he used to derive from various kinds of music, whether it was Hungarian dance music or Mozart’s symphonies. But it was necessarily inspiration, not copy-pasting, which is so much the trend these days.

I have seen how he could adapt a tune or melody that he liked into his own composition. It is amazing to see how beautifully he composed 'Itna Na Mujhse Tu Pyar Badha' [from Chhaya (1961)] out of Mozart’s piece. The way he developed the antara [second stanza] of the song, it feels as if he created a continuation of Mozart’s piece.

Also, as Baba was also a filmmaker, unlike many other music directors, he used to go to the locations and observe the surroundings and compose music on that basis, which was quite unique. I heard from Ma that during the shooting of Parakh (1960), Baba and [lyricist] Shailendraji had gone to the location and were musing over a song to be sung by Lataji [Mangeshkar].

Suddenly a flower fell on Shailendraji’s palm and thence to the ground. He picked it up and muttered ‘mila hai kisika jhumka’ and Baba immediately made the tune of the song. This was the creative process. I have seen that musicians of that era used to take a full day to compose a song, which is impossible to imagine now.

Tell us about your initial musical interactions with your father.

I grew up in a musical ambience, with my father playing the keyboard, mother singing, and my brother playing the drums. Music is in my blood. I used to sing songs while playing with my dolls and could quickly memorize songs made by Baba.

During those days, senior artistes used to sing in a child’s voice. When Minoo (1977) was being made, Ma insisted that Baba take my audition. I sang the song 'Jhilik Jhilik Jhinuk Khunje Pelam' and Baba was quite impressed with my sense of rhythm and melody and hence my journey as a playback singer started, as I sang 'Kaali Re Kaali Re' and 'Dheere Dheere Haule Se' for the film.

I was too young then to understand that I was working with a legend. I only knew he was a big music director. Now I understand that he was not only a musician, but also a poet, a composer’s composer, according to Naushadji. The more I have grown, the more I have understood his magnitude as an artiste.

The only regret is that when started understanding music a bit, I lost him. It was a period of emptiness for me, as I did not know in which direction I needed to move. But then through his blessings, I have revived myself and am working again.

Did he tell you to practise?

Of course! He always used to say there is no alternative to practice or sadhana, no matter how talented one is. He also used to say, “Keep your powder dry. You never know when opportunity knocks and you have to be prepared with your skill and talent all the time, so that if you have to sing a song tomorrow you can give it your best."

Ma used to sit with me and make me practise the sargams. Ma was an unparalleled artiste and whatever I am doing is due to their blessings.

How did your parents engage in musical sessions together?

Their world was different. Often Baba used to get ideas while marketing and then he would come back home in a hurry and ask my mother to memorize the tune. While Ma memorized, Baba wrote down the lyrics. Sometimes, the antara portion of a song was not composed yet and Baba would vanish from the studio, contemplating the tune. Suddenly he would get ideas and write them down on the packet of cigarettes.

How was the experience of assisting him on TV serials?

I was learning the keyboard at the Trinity College of Music then. Baba always wanted me to become a complete musician, not only a vocalist. I used to play the piano with him and also did the programming of many songs. I have learnt a lot while assisting him.

He also penned children’s songs for you. The songs created history in the 1970s.

After my film songs became hit, Balsara uncle [music composer Vistasp Balsara] approached Baba to make songs for children with me. Then Baba started writing those songs. I remember a caricaturist mimicked a bird’s chirping in 'Bulbul Pakhi Moyna Tiye'. It was a playful experience altogether and my gift after every recording was I got the chance to get into his lap. It was my demand for many years until I grew tall and Baba said, “Ar ki pari maa akhon to tui boro hoye gechhis [How can I carry you in my lap, you have grown so big]!"

What do you remember of him as a socially and politically conscious artiste?

I would say he was a socialist. He went underground when a death warrant was issued against him after he composed the song 'Gayer Bodhu' on the great famine of Bengal. He had written so many songs to motivate people against the British, for example, 'Alor Pothojatri', 'Dheu Uthchhe Kara Tutchhe' and 'Gourisringa Tulechhe Shir', during the 1940s.

Baba and his fellow activists went close to people in villages and composed songs there and for them. It was not merely a political ideology; they used to think about human beings in a broader sense. My father had this kind of spirit since childhood as my grandfather was also extremely progressive and patriotic. For example, 'Aaj Noy Gungun Gunjan Preme' (non-film, 1977) is not about romantic love. It talks about universal love. Baba was generally concerned and conscious about human beings and sincerely wished for the betterment of society.

Do you have any memory of his interactions with his fellow musicians or artistes?

I remember gatherings with Manna Kaka [Manna Dey] and Kishoreda [Kishore Kumar] at home and in the studios. They had immense mutual respect for each other. Madan Mohanji also used to come to our house and had a lot of affection for my father. I have seen Punchamda [RD Burman] visiting us during our shows and he was also present at the studio when Baba was working for his last film, Swami Vivekananda (1998). He used to consider Baba his guru. SD Burman used to say, “Amar pola toh tokei guru mane amake pattao dayna [My son considers you his guru, doesn’t consider me]."

As a singer and public persona, how much respect have you received as the daughter of Salil Chowdhury?

I have received immense respect. People call me Salilda’s daughter and I am proud of this recognition and identity. I am proud to be Salil Chowdhury and Sabita Chaudhary’s daughter and it is my duty to carry forward their legacy.

What comes instantly to your mind when you think of the word Baba?

The best human being in the world to me is Baba. Baba means his sweet smile and his warm touch, which I will continue to feel till the end of my life.

He was such an amazing human being, beyond the genius he was and who you are aware of. He had a soft nature and could not bear anybody’s sorrow and that’s why, perhaps, he could do such creations. I have seen him crying so many times while watching the last scene of Anand (1971). He used to run and hide in the bathroom and I would go and console him.