Sen made groundbreaking films which not only painted the stark reality of society, but also stimulated a culture of awareness, analysis and disillusionment while using experimental approaches and techniques. And none of this was the result of sudden inspiration.

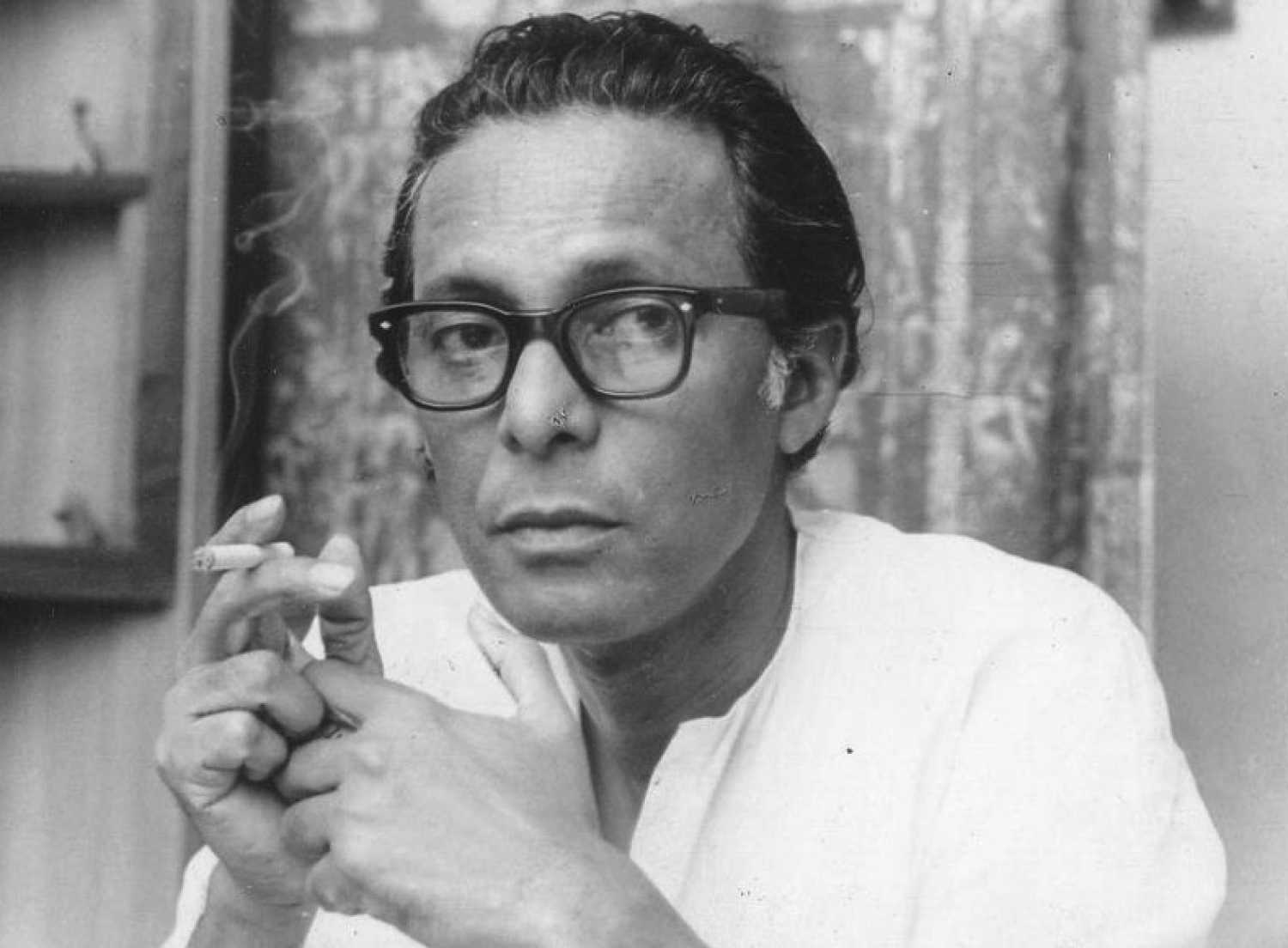

The maverick Mrinal Sen's journey as a political filmmaker – Birthday special

Kolkata - 14 May 2018 23:26 IST

Updated : 15 May 2018 9:06 IST

Roushni Sarkar

Mrinal Sen, who turned 95 today (he was born on 14 May 1923), is often considered the most important Indian filmmaker after Satyajit Ray. He is also admired as the Maverick Maestro. And for good reason.

Sen’s main contribution was to make groundbreaking political films which not only painted the stark reality of contemporary society but also stimulated a culture or milieu of awareness, analysis and disillusionment against the Establishment.

His Bhuvan Shome (1968), Interview (1971), Calcutta-71 (1971) and Padatik (1973) ushered a new wave in Indian cinema with themes relating to social realism and the use of experimental approaches and cinematic techniques.

None of this, however, was the result of sudden inspiration. Political thought was deeply ingrained in Mrinal Sen since childhood. Dipankar Mukhopadhyay, in his book Mrinal Sen: 60 Years in Search of Cinema, has said, “In spite of his well-known reticence about his childhood, Mrinal Sen doesn’t deny that his fascination for technology, his political ideology and his passion to portray life through celluloid, are all rooted in his early years, as he grew up in Faridpur [now in Bangladesh] during a crucial period of our history.”

The filmmaker's father Dineshchandra Sen, a leading lawyer of the town, was the first person Sen looked up to. Dineshchandra was an active supporter of young revolutionaries. As a result, in his early years, Sen unknowingly had the acquaintance of such great men as Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, Bipin Chandra Pal and Humayun Kabir. In fact, Sen was once taken into custody for shouting ‘Vande Mataram’ at the police. He was barely eight at the time.

Sen was also an avid reader who did not follow any pattern of systematic reading; therefore, he read books on social and political history around the world, as well as the science and literature of his time. At the same time, he would never miss a chance when a touring cinema company held special screenings in his town. He had the most fascinating exposure while watching Devdas (1935) and also unconsciously imbibed many lessons on cinema.

As he was growing up, the scenario around Mrinal Sen was changing, as indeed was the world. “As Mrinal entered adolescence, the world around him started changing and it changed his political views also," wrote Mukhopadhyay. "The war of Spanish liberation was in full swing, poets and writers like Ernest Hemingway, WH Auden and Stephen Spender had taken up arms in the fight against fascism. Already a voracious reader, Mrinal read their writings on classlessness and equality of men, and became interested in their views and ideas."

These were the formative years of Sen’s leftist ideology, which attained a new dimension when he moved to Calcutta to pursue physics with honours at the Scottish Church College in 1940. "A new world was slowly opening its doors to him, and he had no inclination to look back," Mukhopadhyay wrote. "Calcutta absorbed him, assimilated him totally. Those were the days of World War II. The city had its share of bomb scares, blackouts, famine, communal riots; with all those turmoils for company, Sen was growing up with the city.”

The growth of Sen’s political consciousness continued in organic fashion with the journey of his life. Like in his Faridpur days, the young man participated in student politics in Calcutta too, and was again taken into custody at the Lalbazar police station. He engaged himself with various circles of professors and intellectuals who gathered regularly to discuss Marxist thought.

Around this time the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA) was formed and it was almost inevitable that Sen would become associated with it. “He witnessed all their productions but strictly as a spectator — he was still unaware of his artistic talent,” commented Mukhopadhyay.

Despite close associations with these groups, Sen always maintained an individual thought process. As he never followed a specific reading pattern, he always kept an open mind to absorbed new ideas from every possible field, not confining himself to the ideas of a few people or theoreticians.

While witnessing the IPTA productions, Sen never hesitated to voice his opinion when he felt something was not quite right. For the same reason, he never became a member of the association. He was a fellow traveller.

To kill time during his days of unemployment, he engaged himself in reading at the Imperial library, which opened new horizons for him every day. He not only read the classics of world literature and Bengali literature, but also followed lesser known authors. He was perhaps the first person to translate Czech writer Karel Capek's works into any Indian language.

The Imperial library also sparked his interest in films, as he randomly picked up Film by Rudolph Arnheim, Vladimir Nilsen’s Cinema As A Graphic Art, and Cinema by Narendra Deb. He became part of the first film society of Calcutta, set up by Satyajit Ray, Chidananda Dasgupta, Bansi Chandragupta, Harisadhan Dasgupta and others. Ritwik Ghatak, Bijan Bhattacharya, and Salil Chowdhury from the IPTA crowd were his close acquaintances as well.

Mrinal Sen worked as a film critic for various magazines, wrote books (My Chaplin, and many more), worked as an assistant for Dhirendranath Ganguly and in Aurora Studios for some time. His early marriage with actress Geeta Sen prompted him to take up the job of a medical representative in distant Kanpur. It was then that he realized he was not suited for anything other than making films.

Around 1943, Sen had witnessed the realities of communal riots, the surge of refugees from East Bengal, and the horror of famine in Calcutta. “The impact of the famine on Sen should not be gauged by the films he made keeping it as a backdrop — films like Baishey Shravan (1960) or Akaler Sandhane (1980)," Mukhopadhyay said. "The fact that the great famine took place in a year which saw a bumper harvest and that it was solely the greed and exploitation of man which led to this unprecedented catastrophe got linked with his philosophy of poverty. In Sen’s development as a filmmaker, famine played a crucial role — just as Partition did with Ghatak’s cinema.”

Mukhopadhyay’s observation could be validated with Sen’s own words, as he elaborated on his philosophy behind making Calcutta-71 in an interview with Udayan Gupta for ejumpcut.org, “I made Calcutta-71 when Calcutta was passing through a terrible time," he said in the interview. "People were getting killed every day. What I have focused on is not exploitation but poverty: how poverty debases human beings, disintegrates the whole pattern, the whole system. That is why I picked out five days spread over 40 years. I took three or four stories of poverty: grinding, ruthless, unrelenting poverty, poverty that is not glamorous.

“We have always been trying to make poverty respectable, and dignified. This has been a tradition which has been handed down to us from generation to generation. You can find plenty of this in Bengali literature.

"As long as you present poverty as something dignified, the establishment will not be disturbed. The establishment will not act adversely as long as you describe poverty as something holy, something divine. What we wanted to do in Calcutta-71 was to define history, put it in its right perspective. We picked out the most vital aspect of our history and tried to show the physical side of hunger is the same. Over time, the physical look of hunger is the same.”

Sen's Padatik essentially reflected the transformation in the political scenario of the city and, with it, the change in the filmmaker’s view too. The film stirred the audience and was criticized for its overtly political approach. “We had arrived at a point when the Left movement was lying low and the leftist parties were in disarray, losing perspective, and isolated, at a time when there was a need for unceasing self-criticism.

"That is why the protagonist in Padatik has unshaken faith in the party, even though he has suffered reverses due to faulty direction. Yet he does question the leadership bitterly and uncompromisingly. Nonetheless, the fact remains that in our country, as elsewhere, you do have the leadership and, to a certain extent, even the cadres go the established way in order to fight the establishment. As the party fights the establishment, it falls victim to it. The party soon adopts the very mores and manners it has been fighting. This is what is happening to our party. This is why a lot of criticism is being taken up these days and there are so many factions even in the most extremist left party — in each of the Marxist variety there are a lot of factions,” Sen said in the same interview.

Sen was hardly attached to his films or the techniques he used. He believed in a dynamic deconstruction through each film that would intrigue self-criticism. The following passage explains Sen’s true motto of filmmaking:

“Have I been able to go into the masses and am I credible? I have seen one thing from my experience. If you don't like a film, you say it is a lousy film or that you don't like it, and the matter ends there. In my films, I have found that people who have not liked them are still quite shaken up by them. I have found them to get angry and disturbed and walk out of my movies saying, 'It’s an anti-social film.'

"I could see that the film has disturbed them to a certain extent, even annoyed them. This kind of reaction could not have been evoked by the standard Indian film. Even the critics who criticize me more than my films ... they write that stuff and I feel that possibly I've made a point somewhere, somewhat differently and effectively, perhaps.

"Otherwise, how is it that these people are provoked in such a manner? And this goes to prove that this kind of film — if we can create conditions whereby this genre of film continues to pour in one after the other — will be able to create a climate which will help the movement to grow and help develop a radical cultural climate. This is what I feel about it.”