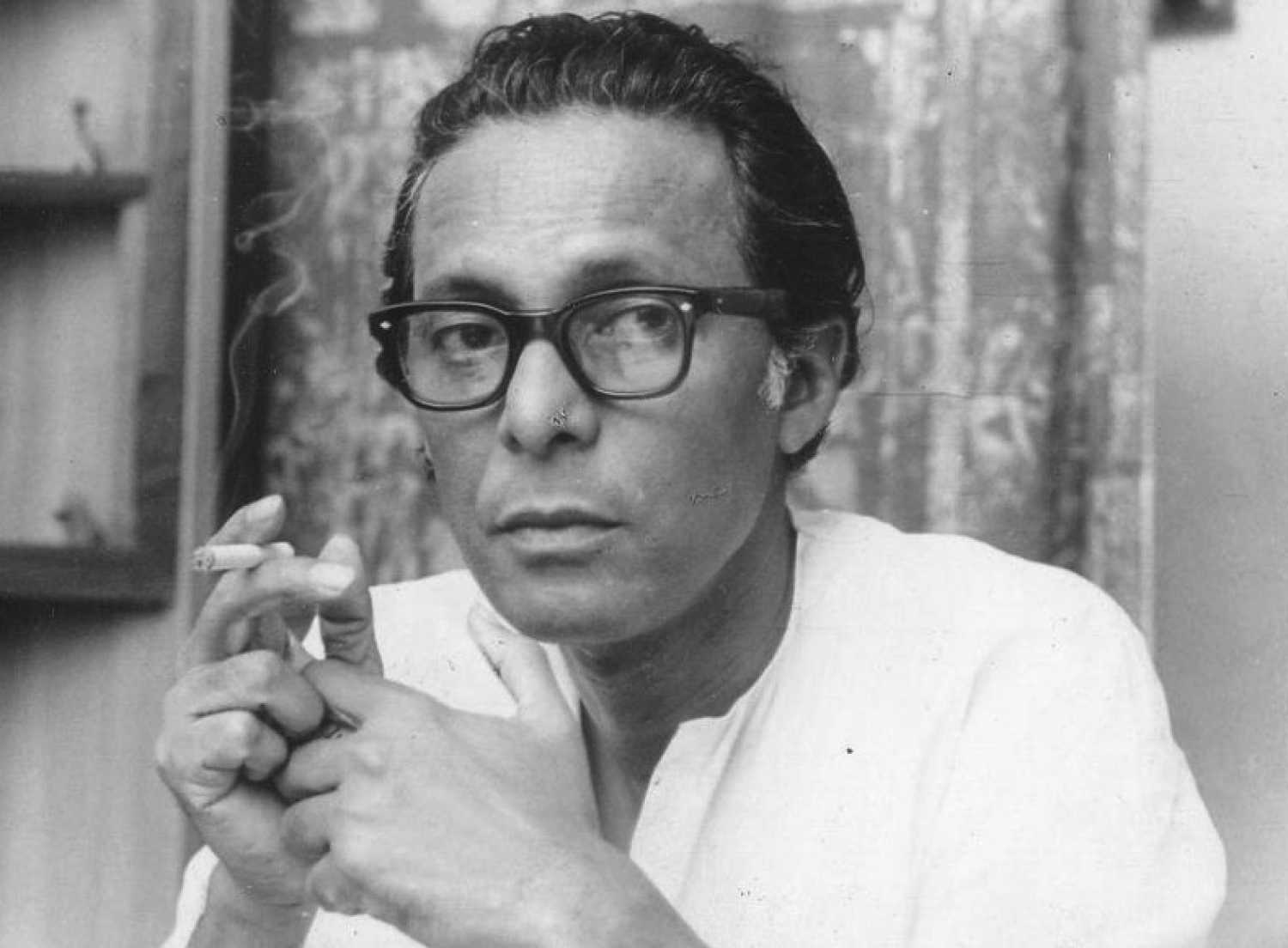

Mrinal Sen, who died on Sunday aged 95, was renowned for pushing the boundaries of what his audience was capable of understanding.

Mrinal Sen (14 May 1923 – 30 December 2018): Last of the great rebels

Mumbai - 30 Dec 2018 19:19 IST

Updated : 19:28 IST

Shriram Iyengar

Mrinal Sen, the last of the great trinity of filmmakers from Bengal which included Satyajit Ray and Ritwik Ghatak, passed into the ages at his residence in Bhawanipore, Kolkata on 30 December 2018. The filmmaker was 95. Sen is survived by his son Kunal, who lives in the United States.

A career that lasted 60 prolific years saw Sen create films, documentaries, and shorts that stood testament to his view that ''filmmaking is a very active fight against the system''. The idea was never reflected more sharply than in Sen's Calcutta trilogy of Interview (1970), Calcutta 71 (1971) and Padatik (1973).

Born on 14 May 1923 in Faridpur in what is now Bangladesh, Mrinal Sen went on to become a pioneer of the New Wave of Indian cinema, which helped the art form / industry to change direction and escape being reduced to a mere form of money-spinning mass entertainment.

Making his directorial debut with Raat Bhore (1955), the filmmaker grew into the craft. With Bhuvan Shome (1969), he finally achieved the commercial relevance that brought a new identity to a style of cinema that would later be called the 'parallel cinema' movement.

Mrinal Sen: The filmmaker as ideologue

Incidentally, it was an accidental reading of Rudolf Arnheim's book, Film, that led Sen to choose filmmaking as a career. His work was influenced by the French and Italian realists as well as by his own experience of the Great Famine of Bengal of 1943.

With Satyajit Ray and Ritwik Ghatak, Mrinal Sen formed a triumvirate of auteurs who created a new idiom for Indian cinema.

From National awards for Bhuvan Shome (1969), Chorus (1974), Mrigayaa (1976) and Akaler Sandhane (1980) to awards at Karlovy Vary, Cannes and Berlin film festivals, the world had begun to understand and follow Sen's work. The filmmaker was also awarded the Nehru Soviet Land award by the erstwhile Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) in 1979, followed by the Padma Bhushan back home in 1981.

Mrinal Sen was the critical insider; he wasn't attached even to his own work: Son Kunal

In 2005, the filmmaker was awarded the Dadasaheb Phalke award for his contribution to world cinema. As late as last year, the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences inducted him into the Oscar academy.

Aside from his Calcutta trilogy, Sen examined morality and urban angst through films like Mrigayaa (1976), which won the National Best Actor award for Mithun Chakraborty, and Ek Din Pratidin (1979) which pushed the cause of women's emancipation. The director soon turned to explore existentialism through films like Khandhar (1983) and Ek Din Achanak (1988).

It was not just in his narrative, but in the form of cinematic techniques that Sen chose to distinguish himself. From the use of broken texts, documentary footage and even references to his own films, the filmmaker continued to push the boundaries of what his audience was capable of understanding.

This did not always go down well. As the Dadasaheb Phalke awardee claimed in an interview, his most acclaimed work, Bhuvan Shome, was often misinterpreted. Even the great Satyajit Ray once described it simply as 'Big Bad Bureaucrat Reformed by Rustic Belle' (Our Films, Their Films).

Satyajit Ray and his equations with contemporary Bengali filmmakers – Birth anniversary special

In the words of Sen himself, "this corruption of a bureaucrat was our intention, but we seem to have been misunderstood by many. They consider this film an attempt to humanize an essentially tradition-bound and corruptible bureaucrat. That was not our intention."

Yet, the filmmaker persisted in 'training' his audiences to attempt to understand, explore and pursue his own complex train of thoughts. In that, the director shaped the understanding of cinema and led to the creation of a generation of filmmakers who have submitted to his influence.

The passing of Sen arrives at a pivotal time when Indian audiences are opening up to the prospect of new narratives and forms with digital platforms, independent films, and styles emerging. He might not have been able to see all the innovations in India's cinematic narrative, but he was there when it all began.