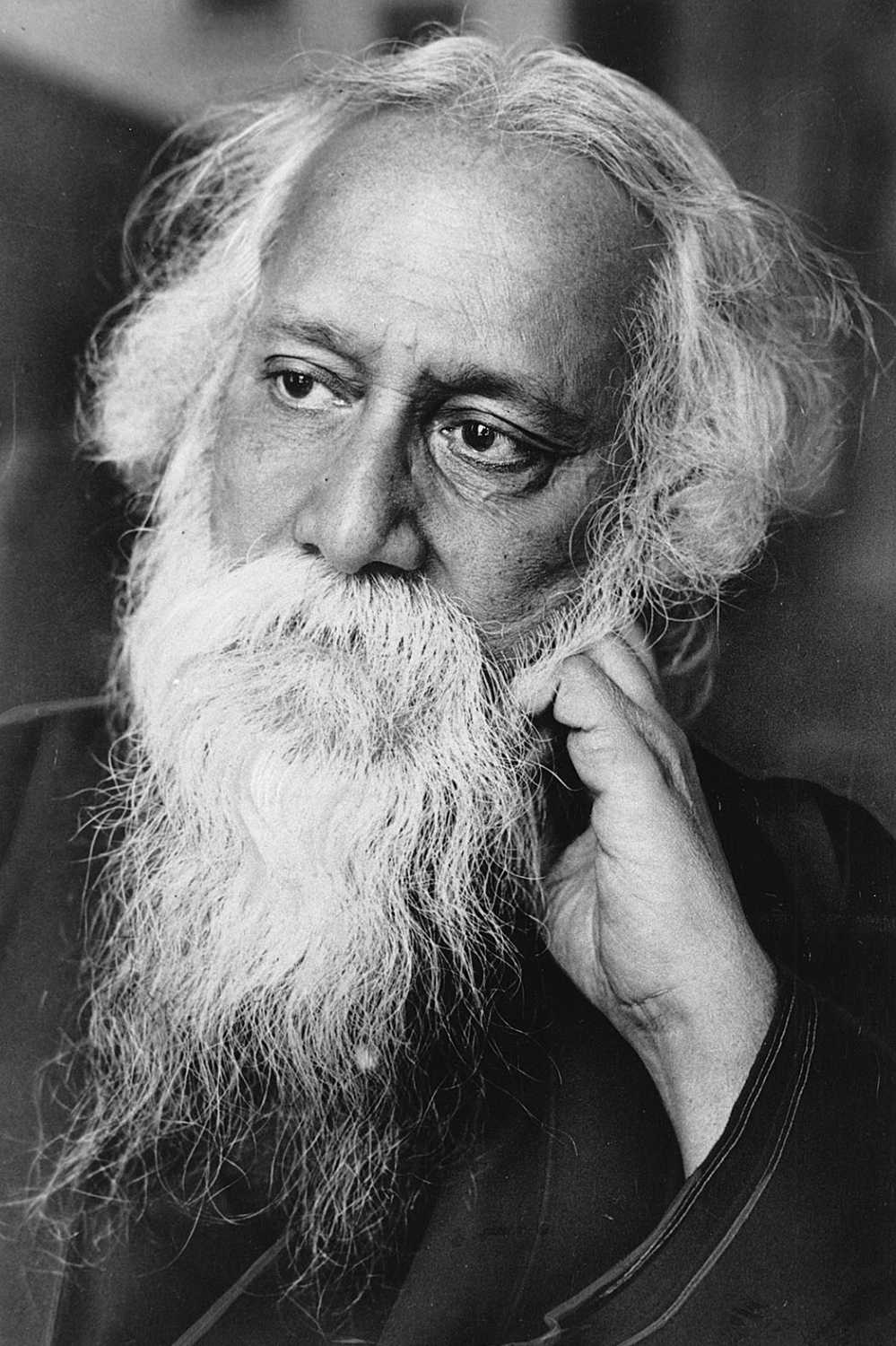

On his death anniversary today (he died on 7 August 1941), we see how Tagore was the first person to share his comprehensive views on many areas of literature, philosophy, politics and art in general, and cinema was no exception.

'Rabindranath Tagore perhaps the first Indian to theorize on cinema' – Death anniversary special

Kolkata - 07 Aug 2018 16:21 IST

Updated : 08 Aug 2018 1:18 IST

Roushni Sarkar

May your wish come true

Lost images be held in captivity

The shadow, dismembered from the body

May arrive and in hand with light

At your celebration of vision

— Rabindranath Tagore in an ode to cinema on the occasion of the inauguration of Rupabani theatre, Calcutta.

Tagore was the first person to share his comprehensive views on many areas of literature, philosophy, politics and art in general and cinema was no exception. According to National award-winning film critic, journalist and author Shoma A Chatterji, Tagore was perhaps the first Indian to theorize on cinema.

In 1928, Madan Theatres made the first feature film on Tagore’s novel Bisharjan. Among the four adaptations of Noukadubi till date, the first was made in 1932.

“The dramatized version of Tagore’s Natir Puja was first staged at the Jorasanko Thakurbari in 1927. It was again staged at the New Empire, Calcutta, in celebration of the poet’s 70th birthday. An impressed BN Sircar, the founder-proprietor of New Theatres, invited Tagore to direct a film version under the New Theatres banner,” writes Chatterji in her book Woman at the Window: The Material Universe of Rabindranath Tagore Through the Eyes of Satyajit Ray.

Unknown to many, Tagore not only directed the film, but he also played a role and selected the cast of the film from Shantiniketan. One of the pioneers of Indian cinema, Nitin Bose, was the cinematographer, while Subodh Mitra edited it. Natir Puja was filmed like a stage play.

The film was released at Chitra Talkies on 14 March 1932; however, unfortunately, prints of the film were destroyed in a fire at New Theatres.

Tagore felt the flow of images should be used to communicate without words. He wrote in a letter to Murari Bhaduri (brother of Sisir Kumar Bhaduri) in 1929, “The cinema, [chhayachitra, in his words] is still enslaved to literature” and conveyed his firm belief that one day cinema will emerge as an independent medium, beyond taking inspiration from literature, and evolve its own language. By referring to the evolution of language, Tagore meant to say “the very composition of the elements, the molecular structure if you like, would undergo a transmutation”.

Arun Roy, in his National award-winning book Rabindranath O Chhayachitra (1986), discussed the influence of Tagore on celluloid and vice-versa. According to Chatterji, “The book elaborates on Tagore’s response to cinema, which swings from a childlike attraction for moving images to a scholarly understanding of the true potential of the medium, from his disapproval of the medium for revelling in the banal and low-brow to his ode to the medium for perpetuating the sublime.”

Tagore’s analytical perspective both explored the positive and negative aspects of the then emerging medium. Though not in very systematic manner, he formed his discourses on the signs and symbols used in cinema, which was turning out to be the manifestation of a collective dream, “the dual characteristic of cinema as opiate of the masses as well as its projection of sublime ideas”.

Another book called Ruper Kalpa Nirjhar: Cinema, Modernism and Tagore by Someshwar Bhowmik throws light on the influence of celluloid on Tagore’s writing. According to Bhowmik, Tagore’s writing turned cinematic in the latter phase of his life.

Documentary filmmaker and former head of the department of mass communication, videography and film studies at St Xavier's College, Kolkata, Subha Das Mollick, writes, “Tagore’s understanding of the social impact of cinema goes hand in hand with his foray into modernist writing. On the one hand he makes amusing observations on how cinema becomes an everyday reality in the lives of people from different strata of society and on the other, Tagore acknowledges cinema as an apparatus of modernism and tries to internalize its technique in his own experiments with modernist writing.”

According to Bhowmik, Tagore’s description of a modern young woman in his novel Two Sisters is much like the character exposition in a screenplay.

Numerous stories from his Golpoguchchho and various novels have been adapted into films, despite the fact that Tagore’s literary works are much more ‘all-encompassing’, ‘alien’ and complex in terms of mass appeal than "the mundane and homespun philosophy of Saratchandra Chatterjee and the romantic spirit of Bankimchandra". Satyajit Ray’s films Charulata (1964) on Tagore’s Nashtaneer and Teen Kanya (1961) on Postmaster, Samapti and Manihara form a fresh and separate ground of debate till date.

Also, his songs have been specifically used in various films to prolong particular cinematic sequences and magnify the essence in them. Chatterji writes, “Bimal Roy’s Sujata made telling use of a scene from the Tagore dance drama Chandalika to bring across the acceptance of an ‘untouchable’ by Ananda, the Buddhist monk, juxtaposing this against the ‘untouchable’ Sujata of the film.” Many of such instances can be found in Rituparno Ghosh’s films Asukh (1998), Utsab (2000) and Shubho Mahurat (2003).

From the silent era to the present generation digital platform, throughout the past eight decades, Tagore’s works have been remoulded, introspected and represented with their relevance to contemporary society. His adaptation from Bisharjan to Tasher Desh (2013) by Qaushiq Mukherjee sketches an enormous shift in the history of cinematic adaptation of literary works.