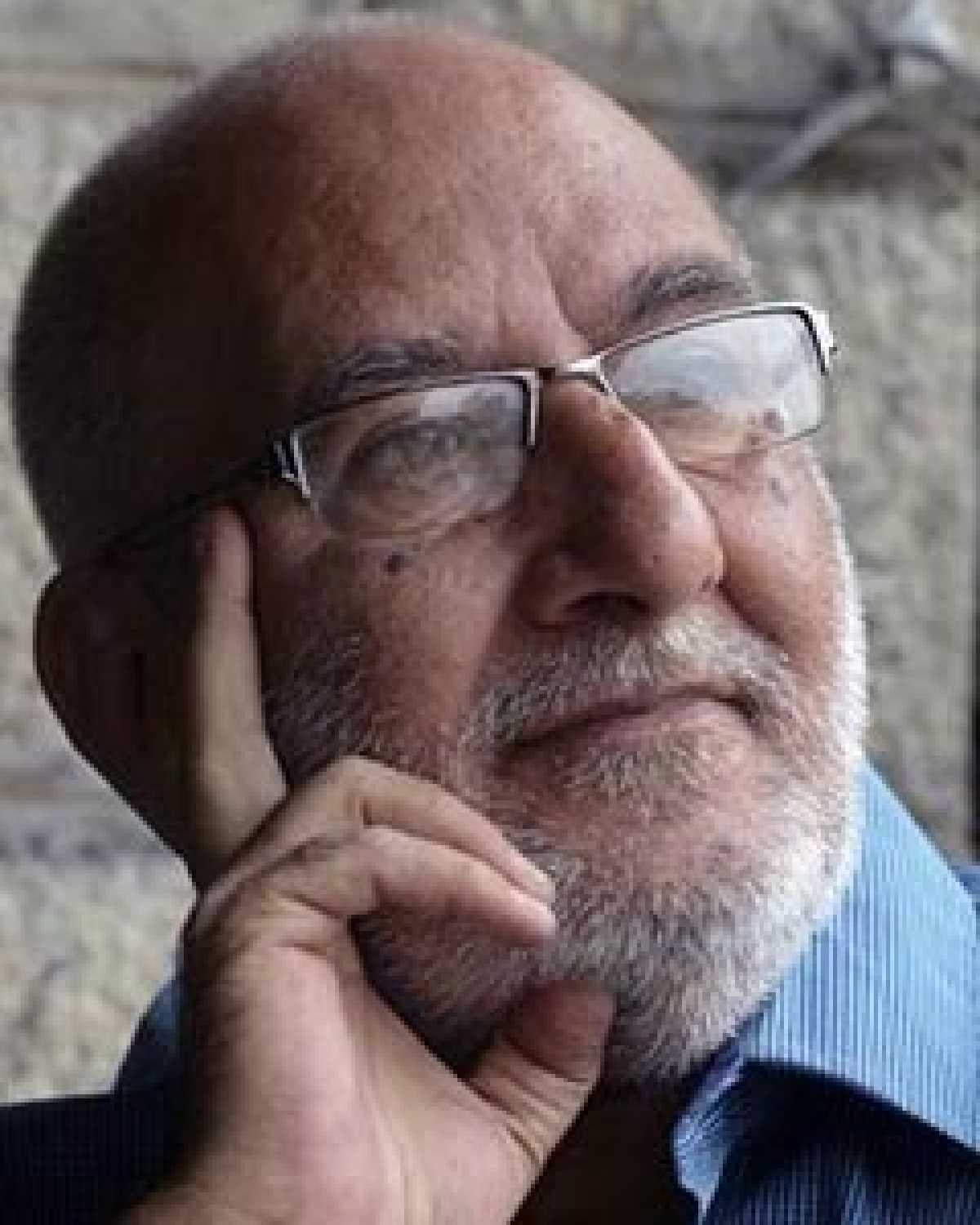

In an exclusive conversation with Cinestaan.com, Kamal Swaroop speaks about his film on the painter and his thought process while making films.

One has to make a decent film that is useful: Kamal Swaroop on Atul Dodiya documentary

New Delhi - 19 Sep 2017 19:25 IST

Updated : 19:53 IST

Sukhpreet Kahlon

At one moment in the film Atul, artist Atul Dodiya ruminates about his work and says he wanted to explore “what happens when creativity becomes the subject matter”, a statement that resonates as much with the work of Kamal Swaroop, who, as a filmmaker, explores the process as much as the subject in his films.

Since his experimental feature Om Dar-b-dar (1988) that won the Filmfare critics' award for Best Film in 1989 and became a cult classic on the festival circuit, Swaroop made the National award-winning docu-feature Rangbhoomi (2013), based on the life and times of Dadasaheb Phalke, followed by a few documentaries.

His latest documentary Atul follows the work of painter Dodiya as he traces his influences and journey as an artist. In doing so, the film explores the elements of his art and attempts to understand the thoughts and impulses behind his creations. The film was screened at the Open Frame film festival by the Public Service Broadcasting Trust (PSBT) in Delhi.

In an exclusive conversation with Cinestaan.com, the filmmaker spoke about his latest film and his form of filmmaking. Excerpts:

The documentary on Atul Dodiya is very different film from your earlier films, even in the choice of your making a documentary. What was the motivation?

This was for educating myself also, like the previous film on Phalke was about educating myself, but this one was about learning from Atul. Learn about his work and a bit about the history of art. So, because of that selfish interest, it was the main motivation that I will learn something from him, especially their sense of beauty, design and how they work. I have great interest in the arts and crafts, so I thought it was a great opportunity especially when somebody is opening up and giving you his precious time. This was the main thing, not the film; but getting to spend time with him.

So the film was the medium through which you were able to achieve that?

Correct, correct.

Given the strong visuality in your films, your journey as a filmmaker seems to naturally lead you towards a film on a painter and the medium of painting.

The responses are very natural. I didn’t prepare myself while making this film. Atul was talking so beautifully, and the paintings are so nice, and I’m not interviewing him in the film. Most of the time, I am silent. So he must be reading my mind and fathomed what I am looking for and imagining what I want to hear. Otherwise, suppose I was an intellectual from South Bombay or somewhere, he would have spoken in English, but he is speaking in Hindi because he must be thinking that I speak in Hindi.

In Hindi, there is no violence of intellectualism. We use day-to-day speech, but in English, you can mystify things. Most of the people who write about the painters, they mystify things through the language that they use and one can take one piece of writing meant for a certain painting and put it on another painting and you wouldn’t know the difference. So that was the difference.

In one interview, you had talked about how, in Om Dar-b-dar, you were dissecting frogs, and in Rangbhoomi, you were dissecting Phalke. In Atul, too, you are dissecting the painter as you have managed to bring out the thought process of an otherwise reticent person, which takes the form of self-exploration in a way.

Because I am not doing it, he is doing it himself.

But it’s happening through you…

Yes, but there is no violence happening. I’m not ripping him apart. I have no weapon with me, so it’s a very non-violent activity on my part.

In the interaction after the screening of your film, you mentioned that if you had gone beyond the confines of the norms dictated by the PSBT, you would have made a different film.

When Atul is not alone and he is with friends, the market, the buyers, sellers, when he was coming into the reality of the community. In the paintings there is some kind of sacredness, but when you get into the market of the painters, that world is very different so there is a violence and a different kind of drama. There is a theatre involved of people talking to each other, their envies, their greed, their fear.

There is almost a reverential stance towards Atul in the film and as viewers, we are transformed into students, learning about his art. Did you imagine the film taking this form while you were making it?

Yes, otherwise, if I start posing like I am a great filmmaker and interview him, then I will bring in my personality, which may block him. Then he would have the choice to either accept my personality and my projection or counter it or do a dialogue with it. So I thought that to begin with, it is about him, so why bring in my personality.

But later, when I was with him and his friends, when he did an exhibition in Delhi, then the Delhi public was there, the buyers and sellers, the high society, la dolce vita, you know, the good life. That is a different world. Of course, that’s not about his paintings, but it is his world, there he is a star. Then you will go into the money, the kind of money going into this business. Then you will go into the fact that he has five people working with him, it’s a factory he runs in his studio, each canvas costs one lakh, a blank canvas, and the brushes are for Rs20,000; the colours are expensive, so it’s a different world and that’s another story.

But for the people and for PSBT I did what was needed. It is not that one has to make a great film, one has to make a decent film which is useful. People should like it, learn from it.

When you say a film needs to be useful, it’s very different from, say, Om Dar-b-dar. Is this view because of the difference between you as an adolescent filmmaker and you now, something you mentioned in the interaction earlier.

I am a humanist now. When you are young you are not humanist. When you grow old, you turn kind, gentle, you are not a terrorist, you are more empathetic and you realize your limitations. And you realize people are so talented and creative. When you are young you feel that to be great is your birthright and later you realize that everybody has their unique space and the idea that you are the best and you are the greatest becomes finished.

But you also spoke of yourself as a destructive filmmaker.

Yes, yes, but calmer now and not too much desire to prove. Otherwise, there would be lots of expectation from Kamal working on Atul, and people would want to know what is Kamal’s contribution to that, so I’ll desperately try to find an innovative idea so it becomes Kamal’s work. I didn’t have that.

Yes, you have refrained very consciously from interfering with the flow.

I don’t think much now. Whatever comes very easily and effortlessly to me, I go for that. Not deep thinking. Which means instinctively, doing naturally what comes to you and the choices you have. Doing whatever can be done with the given resources, you do a decent job and, of course, the film is for television and the PSBT people judging it should also feel satisfied with it. And if it’s good enough people will also like it. In a public broadcasting forum, you shouldn’t say that you should make a great work of art. You do whatever you can do to your best ability.

You have often expressed your desire to make a film on Phalke and said you would ideally want Aamir Khan to play the role, but you would also want the deep baritone of Amitabh Bachchan for the role.

I started out wanting to make a feature film on Phalke. In that process a book came out, so I desire something but the offshoots of that may be different. So the result need not exactly be a film with Aamir Khan or Amitabh, but you keep working on it and something else will come which will surprise me. Most of the times, that’s what happens and I am open to that.

So I don’t think I can do something that is manufactured and the end result is inherent in that. People know exactly what the end product will be when they make a film. I don’t think I can do that. We are more interested in the process and what is the real goal or real desire I don’t think anybody knows, but it is there in your system and it guides you unconsciously, but it is not possible to be fully aware of what you really want.

Originally your idea was to use the 3D format for Atul and embed layers on to the paintings, which got me thinking about technology. What are your views on digital technology and its use?

I was already prepared for that. I started my career with ISRO [the Indian Space Research Organization] and worked on computers. Om Dar-b-dar was almost predicting the arrival of video, that hybrid form of the digital and analog, so it was almost predicting that. So I’m very open to it as in the digital I can create layers.

Yes, exactly. Digital technology seems very conducive to the cinema you create.

For me it is fantastic. Within a single image there are many references, so it is a composite image, so it gives me fantastic freedom now. In earlier times, optically there were still limitations. I am thrilled that this technology has come during my lifetime and I will explore that technology in my film on Phalke.

Other than Phalke, what projects are you working on?

There is a script I have written based on a novel by the Irish writer Flann O'Brien, The Third Policeman. I have adopted that into a script called Omnium, which I have been working on for some time. That is my obsession. I also want to make a commercial film Miss Palmolive All Night Cabaret and, of course, Phalke. These keep me going.