On the 94th birthday of the master filmmaker, we look at how his films stand out from his other great contemporary, Satyajit Ray.

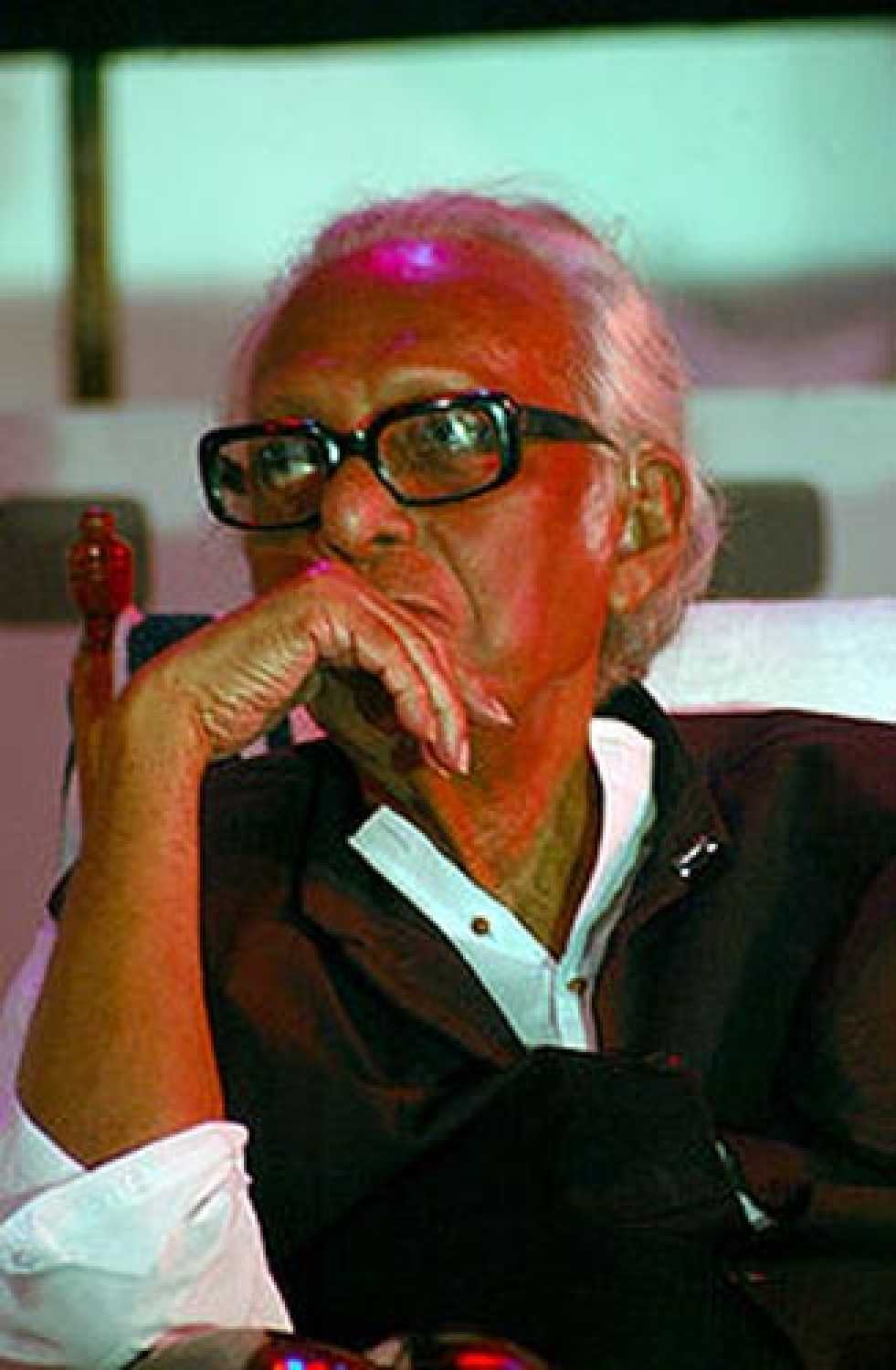

Mrinal Sen: The filmmaker as ideologue

Mumbai - 14 May 2017 21:58 IST

Updated : 03 May 2018 0:06 IST

Shriram Iyengar

On 10 October 1965, The Statesman newspaper of Calcutta carried a letter by Satyajit Ray criticizing the recently released Akash Kusum. About the film's theme, Ray wrote, 'May I point out that the topicality of the theme in question stretches back into antiquity, when it found expression in that touching fable about the poor deluded crow with a fatal weakness for status symbols?'

Given Ray's reputation, the paper was soon deluged by a number of replies, including one by the film's director, Mrinal Sen. Answering Ray's critique, Sen wrote, 'To conclude, I do not, by any chance, wish to take refuge under the fabled crow's wings and claim to be an Aesop or a Cervantes or Chaplin. I have made a film called Akash Kusum and that is all.'

To this, Ray replied, paraphrasing the French filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard, that 'a crow film is a crow film is a crow film'.

Over the span of a month between August and September, the two celebrated directors had indulged in a battle of words and wit that dragged Cervantes, Aesop, Ibsen, Gorky, Wilde and even Hamlet into the discussion. It was a mark of the erudition of the two men who represent the best in Indian cinema history.

Mrinal Sen had never wanted to be a filmmaker. Born on 14 May 1923, he earned a post-graduate degree in physics from Calcutta university before a light reading of a book on film aesthetics, Film, by Rudolf Arnheim, drove him to cinema, a change of direction that would set him on the same path as two other giants, Ray and Ritwik Ghatak. The trinity would shape the consciousness of Indian cinema and the 'New Wave', as it came to be called.

Of the three, Ray and Sen shared the longest rivalry. Ghatak's sudden death in 1976 led to some recalibration of their chemistry. But at heart, they remained fierce competitors. As Sandip Ray, Satyajit Ray's son, said in an interview, "You cannot perform in a vacuum. Only when you have stiff competition do you have the urge to excel. Mrinal Sen and Ritwik Ghatak’s presence naturally urged my father to outshine himself. I am sure that my father’s presence had a similar effect on them."

Nowhere was this effect more pronounced than in their Calcutta films. Ray and Sen both made trilogies on their 'karmabhoomi', Calcutta. Ray studied the urban middle class's quest for material fulfilment and its moral ambiguity through Pratidwandi (1970), Seemabaddha (1971), and Jana Aranya (1976). Sen replied with his searing debate on political economics in the city through Interview (1971), Calcutta 71 (1971) and Padatik (1973). While Ray was an auteur indulging in objective political activism, Sen was an audacious political activist using the camera as his weapon.

It is here that Sen stands out. Filmmaker Shyam Benegal, a contemporary of the two giants, told Cinestaan.com, "They [Ray and Sen] were two completely different filmmakers. Although, I think, they agreed on the aesthetics of what constitutes a work of artistic excellence. But both saw it distinctly. Ray would be seen as a person who would write a novel. Mrinal would write a tract. Ray never took sides. Indeed, he made political statements, but not in an obvious way. But Mrinal was very open about where he stood."

A lifelong member of the Communist Party of India, Mrinal Sen never took politics lightly. Along with Ghatak, he shaped politically conscious cinema. Yet, he possessed the gift of cinematic technique; the ability to deviate from the narrative form made him special. In Interview (1971), the audience faced a radical introduction to the protagonist (played by Ranjit Mullick) in a running tram. Suddenly, the character breaks the sacred fourth wall and indulges in a conversation with the crowd in the tram. The revolutionary sequence was both a formalistic and narrative invention in Indian cinema.

The monologue goes: 'It is all my fault. You must be curious, so let me confess. It is indeed my photo. But I am not a star. By any means. My name is Ranjit Mullick, I live in Bhawanipur, and work for a weekly magazine. I go to the press, correct the proofs and do other tasks. I have a very uneventful life, you know? Yet that is precisely what attracted Mrinal Sen... yes, yes, the filmmaker, you know? He said, ‘My camera will just chase you right through the day.'

At one point in the scene, the roving eye of the camera even captures the cinematographer, KK Mahajan, perched precariously on top trying to film the entire action.

This style defined Mrinal Sen. His political ideology did not restrict him to staid narrative forms. As Benegal said, "He was a very restless person. Always trying out different things, particularly in the three decades of the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. He tried out all sorts of experiments in form, storytelling, and style. Chorus (1974) is one of them. Interview (1971) was one."

Chorus (1974) stands out as a reverse allegory, with the workings of heaven described as a bourgeois society. Coming back to Interview, and Ray's Pratidwandi (1970), there are several elements that are similar and yet stand apart. For instance, during the eponymous interview, Sen's protagonist is asked, 'What is the most important event to take place in this decade?' This question is also asked in Ray's film. It is here that the political ideology of the two directors appears. While Ray's protagonist gives the answer, 'The Vietnam war', Sen's hero simply smiles and answers, 'My interview!'

Ray's protagonist answers like the educated unemployed angry with the system, but Sen's is the more direct comment on realism. There couldn't have been a more happening event in a decade of socio-political and economic violence than the prospect of a job. Everything else paled in significance.

In 2000, Sen wrote, 'My question is a very vital one: whom do I, the communicator, address? The metropolitan variety or the rural masses? Which vocabulary, and going further, which wavelength, as a necessary adjunct, do I choose? To work out an ideal situation, should I try a middle path — both in terms of words and images, and in terms of attitudes? In other words, do I have no choice but to compromise?... All these are likely to raise diverse issues on the aesthetic front with hardly any easy solution. Or, can such a debate as I envisage lead to any tangible conclusion? I wonder.'

Benegal explained, "Mrinal had very strong views on political, social, and economic matters. That showed in his work in a much more direct way. Often that was a criticism put up against him, by no less than Ray, saying his films were far too ideological, and took very strong positions. As a storyteller, you don't take sides. You have an objective position, or attempt to have an objective position. He [Sen] was a very straightforward person — this is right, and I believe it to be right, and he would say it."

While Ray's objective eye views the city from a bird's vantage point, Sen looks at it from the street view. His was the view of the common man, fighting on the streets. The opening sequence from Calcutta 71 (1971) is a good example of this sight.

In the aptly titled Padatik (1973), scenes of political discussion in a dank printing room of a newspaper transition into the dark but comfy spaciousness of an advertising office. While the first discussion revolves around the futility of the revolution, the second sees the same poverty and futility being used to sell a food product. The scene is charged with political Semtex.

Even the opening sequence of the film, a treat for students, stitches gunshots with the sound of the printing press. The shaky visuals that follow make it a shocking introduction to the violence that encapsulated the city during the time.

Despite his strong political views, Sen went on to make films in multiple languages. While his laurels rest on the path-breaking Bhuvan Shome (1969), the director was prolific in his work. He transformed Premchand's 'Kafan' in Telugu for Oka Oorie Katha (1977). He launched the incredibly talented Mithun Chakraborty in the brilliant allegory on class distinction, Mrigayaa (1976). Despite the varied languages, he never deviated from his central ideology.

The rivalry between Sen and Ray remained restricted to ideology. On a personal level, both had healthy mutual respect. Even Sen admits after reading an emotional letter written by his son after viewing Ray's Aparajito (1956), "Every time I watch the film, I discover in it a stupendous journey through distressed adolescence, stepping into refreshing youth and always looking into the wide unknown world. Here, in Aparajito, I watch the master’s unorthodox approach to the analysis and unfolding of the relationship between a mother and her only son, growing into adulthood." Ray, for his part, once re-screened Baishey Shravan (1956).

The two formed one of the most powerful branches of political, non-commodity cinema in India. Their work, set in their favourite city, around their favourite culture and people, is still drastically different. As Sen remarked, "It is up to each communicator to choose his or her own shade of grey." After all, there is no black and white in the real world.