On Bimal Roy’s 108th birth anniversary (12 July), Rinki Roy Bhattacharya speaks about her book on the making of the 1958 classic Madhumati, directed by her father.

I’m continuously discovering stuff about dad: Bimal Roy's daughter Rinki

Mumbai - 12 Jul 2017 12:45 IST

Updated : 21:49 IST

Sonal Pandya

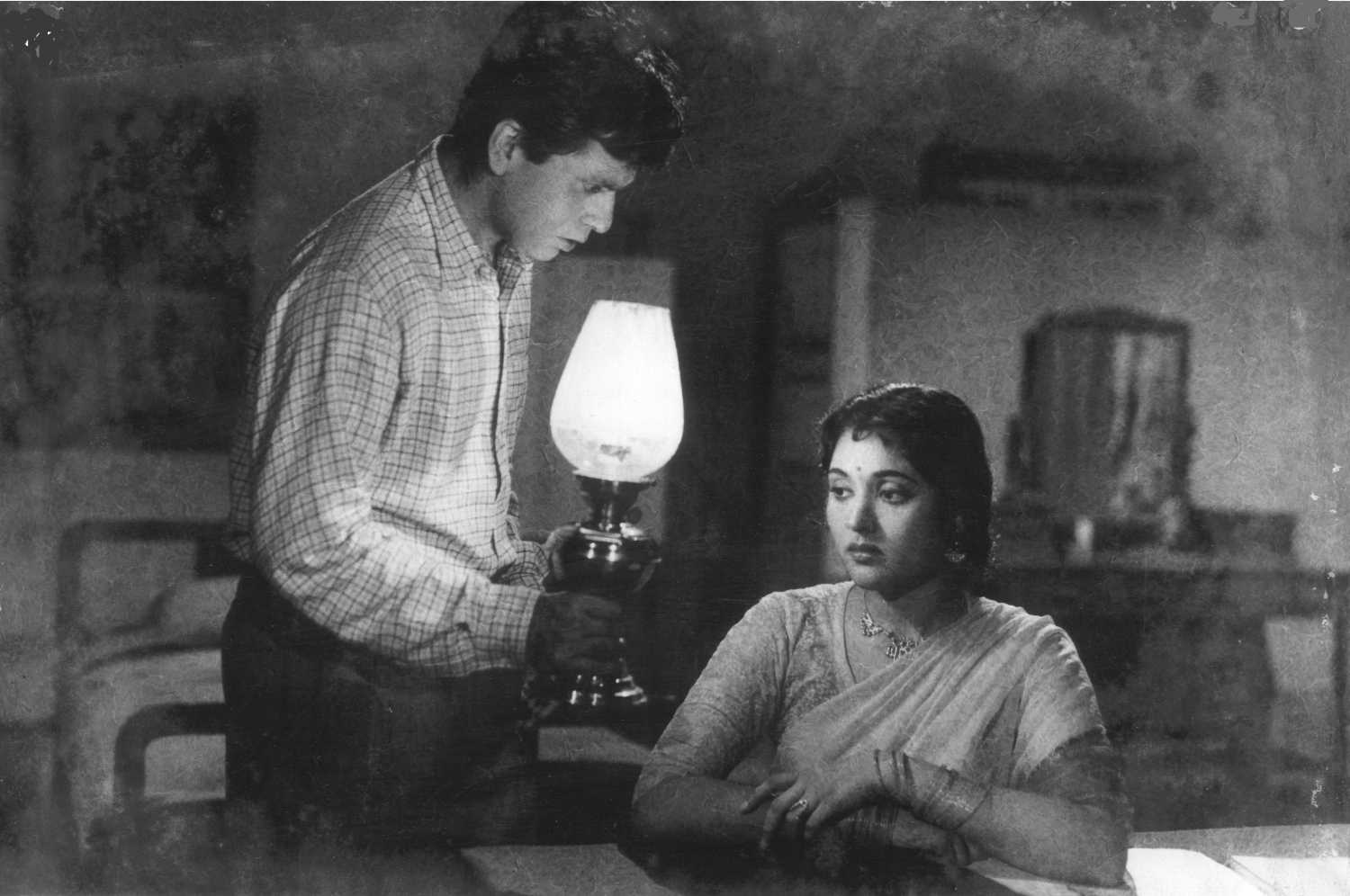

With Dilip Kumar and Vyjayanthimala as star-crossed lovers, Madhumati (1958) set the screen ablaze with its ingenious storytelling and stunning visuals. The film won nine Filmfare awards and the National award for Best Feature Film in Hindi. It was deemed the most commercially successful film to emerge from Bimal Roy Productions, which had earlier produced Do Bigha Zamin (1953) and Devdas (1955).

More than 50 years later, Bimal Roy’s daughter, Rinki Roy Bhattacharya, retraced the footsteps of the film from Mumbai to towns in Uttarakhand where memorable portions of the film were shot. The final product was the book, Bimal Roy’s Madhumati: Untold Stories from Behind the Scenes, which revealed tales from the shoot that no one had heard of. The book is the first that Rinki has written by herself. It is also being translated into Marathi.

The book is an endeavour to keep her father's memory and films alive. Rinki feels Bimal Roy hasn’t been properly honoured by the government of India. In this interview with Cinestaan.com, she speaks at length about her father’s legacy and why the book was meant to be written. Excerpts:

How did you embark on writing the book on Madhumati?

I have written about that in my introduction how it came about very suddenly. There was a young journalist, Taran Khan, who came to interview me on Bombay Talkies and we got chatting and having tea. And then I said, 'I’m thinking about writing — maybe I’ll take one of dad’s films, possibly Madhumati'. So she just jumped up and said, 'Oh, Madhumati is a family favourite'. So I asked why. A lot of people say Bandini (1963). It made me curious. Then she told me the whole story — that one of her aunts [Razia Husain] was an absolute devotee of Dilip Kumar. She was a high school girl and the aunt claimed that she had seen the shooting of Madhumati. That shook me up.

Finding somebody who has seen the shooting of Madhumati [is rare] because we never went to see the shooting [since] it was not a family station where my father shot. Usually he would take the family. I took the aunt’s number, that very night I called and she almost fell back. 'My god, Bimal Roy’s daughter!' I made her promise [to write down] whatever she remembered of the shooting. She was only 17 [then] and she had a box camera. Those are wonderful photographs and there is a lovely shot of Dilip Kumar in that location. This is how it began.

Photo: Razia Husain

What a wonderful coincidence!

It was as if the book was meant to be written. Frankly, I was not even confident what I would come up with. It was a two-year project and I went around, I approached other people because I also wanted to include a little bit about my father’s production house [Bimal Roy Productions] and how it came about. I had heard bits and pieces from Hrishikesh Mukherjee. [Now] nobody’s around.

It must have been difficult to get information on a film decades after it was shot. At that time, there was no thought of archiving the process.

At one point, it seemed as if my trip was futile when I went to Ranikhet [Uttarakhand]. When I was there, the whole area felt like I was in the midst of Madhumati. The whole landscape was unchanged. The same trees and the bird call, which is so strange, it’s the same sound my father has used again and again in the film. There was no sound design at that time. Now you see a sound design credit. [Then] the director was the sound designer, especially in my father’s case. He had everything in his mind in a layer — what it will sound like, what it will look like. He was a complete filmmaker in that sense.

I didn’t have any guide. Nobody was there to tell me, yes, the shooting happened here. I just discovered people on the way like a tea-shop owner who had been a young boy when the shooting happened, but he was not very welcoming. His tea shop is on the way to where actually the shooting took place and we never went there. Sainik School Ghorakhal, which belonged to the nawab, where Razia and all used to spend their summer holidays. That’s exactly where [the song] ‘Suhana Safar’ was shot. They remembered seeing the shooting when Dilip Kumar bends down and smells the flower that was in the garden.

You were fortunate enough to speak to the main leads, Dilip Kumar, Vyjayanthimala and Pran. How did they remember the film?

That was one of the things that jolted me because [Pran] had lost his memory. I thought I would sit with him and chat. I went to invite him for a special show of Madhumati. Of course, he had not seen me before, but I knew his daughter very well. His family [then] came to the show. I am very aware of the fact that there is no documentation. That also sadly includes my father’s works. I’m trying desperately to save Madhumati, the film, but the negative is in such a bad shape. Right now, I am greatly concerned about restoring it.

In the book, you also talk about resisting turning the film into colour for a re-release.

You can’t colour Madhumati. The films which have been colourized, I don’t think it works. The charm of [Madhumati] is in black and white. It's shot [that way] and it’s not just black and white, there are so many shades of grey. My father’s films are not just a stark contrast of black and white which is also a mistake. It has so much depth and shades. In a frame, you don’t miss colour. Also, they belong to a certain era and symbolize that era by being in black and white.

Besides the big names, your book honours the little-known technicians who worked on the film. How important was it that they receive their overdue recognition?

Especially [assistant editors] Sakharam and Das Dhaimade. Nobody knows Das. I honoured him but he couldn’t even come because he was so old. When I went to meet him and tell him the news, he told me, 'You know, I was waiting for this. This is the biggest honour for me.' [These technicians] have really gone unacknowledged after having edited films like this. What is the industry doing?

You have uncovered a lot of new information about the film in your research — from why it was denied a silver jubilee to who actually edited a large portion of the film.

They interest me, it’s not just gossip. It’s establishing something which was bad practice.

What did you discover about your father, the filmmaker, over the course of writing the book?

I’m continuously discovering stuff about him. I’m probably the only child of his who has been relatively close to him, followed him, celebrated him and I’m still surprised by him. [I have recently learnt] that he walked into Mohan Studios and gave it new light because it was going to be shut down in the 1950s. Because such fantastic films were being made, it acquired new light. He was also in that sense an activist. He didn’t belong to any NGO, but he was very much aware of the social ills and wanted to try to do something about them.

For many of the people in the region where Madhumati was shot, it was the only film shot in those parts. It was their big brush with glamour.

Not just that, nobody minded it. My father really respected the sentiments of the people. He couldn’t get extras there so he used housewives in the song, ‘Zulmi Sang Aankh Ladi Re'. [My father also highlighted] exploitation of the people by the local land mafia [in Madhumati]. When I went now, I could see it was still happening. They burn down, they set fire to forests to get money from insurance. [In Madhumati], there was that angle also — deforestation.

When you went to the locations, you must have realized how Bimal Roy had meticulously planned for the film.

My father believed in the bound script. He never went to a shoot without a script. There were rarely any changes because he was called the ‘confidence man’. He would sit with his entire team. The team was his cameraman, his editor Hrishikesh Mukherjee, his scriptwriter Nabendu Ghosh. They would sit and discuss threadbare every frame.

What really mystified me that it was such a long journey even today when I had to go to Ranikhet or Ghorakhal where it was shot. I had to first go to Delhi, take the night train to Kathgodam, then drive up. In three phases! Imagine how difficult it would have been in those days, take a whole film unit and a huge Mitchell camera which four people have to carry with the stand and go to such a far-fetched place where there is nothing. Even eggs you couldn’t get for breakfast. You had to go to the village. I feel he was fascinated by that area. My aunt used to stay there; his favourite sister, he used to visit her in the summer months in Mukteshwar. He didn’t shoot there. But it is close to Nainital.

The story was written by Ritwick Ghatak for this very commercial film.

I always joke, everybody’s always trying to make a hit film. We have the formula, but only 5% of films become hits. This is one example where everything was used and measured — this has a comedian, a villain, beautiful songs. It’s the only film of my father’s that has so many songs.

Ritwick Ghatak had written the story and he gave it to my dad. It’s a ghost story. [Ghatak] was my father’s assistant in Kolkata. He was a comrade and he used to make dedicated leftist films. Most of my father’s films are from literature except for Madhumati. It was written for my father.

Click here to purchase Bimal Roy's Madhumati: Untold Stories from Behind the Scenes