The famed filmmaker was at the ongoing International Film Festival of Kerala (IFFK), where he spoke of identity, the perils of partition and the ideas behind his films.

IFFK 2017: The Song Of Scorpions director Anup Singh recalls horrors of Partition, loss

Thiruvananthapuram - 14 Dec 2017 16:00 IST

Anita Paikat

Along with a long line-up of Indian and international films across sections, the International Film Festival of Kerala (IFFK), is also hosting a series of panel discussions, open forums and conversations. On 12 December, the festival invited famed director Anup Singh for a rendezvous with Malayalam filmmaker, KM Kamal.

Calling Singh 'one of the master filmmakers emerging in the world of cinema', Kamal began the session with introducing Singh and his works so far.

Singh was born to a Sikh family settled in Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania. He came to India to complete his studies and graduated in English literature and philosophy from the University of Bombay and moved to the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII) for film studies.

His first feature film was Ekti Nadir Naam (2003), a Bengali documentary-styled film based on the life and works of filmmaker Ritwick Ghatak. Shot in India and Bangladesh, the film won Singh the Silver Dhow Prize at the 5th Zanzibar International Film Festival. However, it was his second feature that had cinephiles flocking towards him.

Punjabi film Qissa: The Tale Of A Lonely Ghost (2015), starring Irfan Khan, Tillotama Shome and Tisca Chopra, dealt with the loss of identity during Partition, and how it stays on and is passed on to the next generation. The film was screened at the 38th Toronto International Film Festival (2017) in the Contemporary World Cinema section, where it won the Netpac Award for World or International Asian Film.

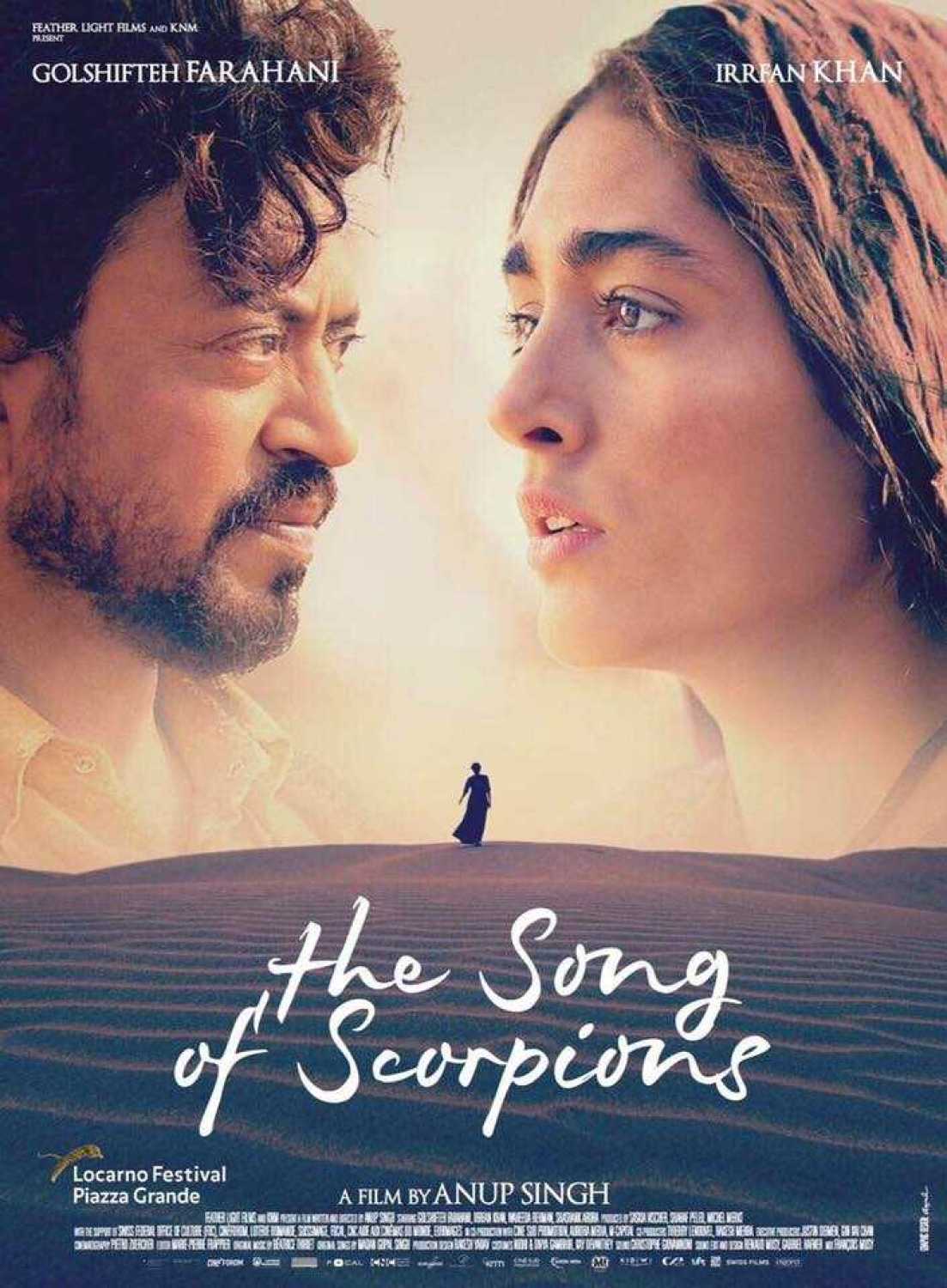

Singh's third film, The Song Of Scorpions (2016) is still making the rounds of films festivals in India and abroad. Based on the idea of vengeance and redemption, the Rajasthani film had it’s world premiere at the 70th Locarno Film Festival.

Noting the diversity of Singh’s filmography, in terms of language and region, Kamal asked Singh about his journey. “Journeys are very strange,” Singh began, adding that journeys take you to the unknown — both inside you and the outside.

“When you are on a journey, you suddenly realize your language is no longer yours, your identity is no longer yours, and what you are faced with is the unknown,” he added. There are two ways to deal with this, he said, one by reaffirming yourself and stick to your identity, and second by realizing that the identity that you have formulated for yourself is as much a journey, as the journey you are taking. If you allow it, the journey will open the doubts within yourself, constantly — in terms of nationality, religion, gender or border.

Singh shared that he wanted to look at the border or the idea of Partition in a way that it is not often seen within Indian cinema, except for filmmakers like Ritwick Ghatak. He wanted to analyze separation not as something that destroys, but as something that unifies in a new way.

On being asked how Singh arrived at Partition and the history of wounds in Qissa (2015), Singh said, “You know certain films belong to their times.” When the filmamker first came to India he had no idea of the religions and castes in India, even until his first five years in the country. But the increasing intolerance to caste and religion made him question his own beliefs. Qissa, he said, was a product of this unease in the country. The film also had a lot to do with his own family history.

Post Partition, Singh’s grandfather decided not to stay in either of the divided parts, India and Pakistan, and moved to Africa. The family had to leave behind their home and everything they owned and start afresh in an unfamiliar space. Along with the material loss was also the loss of a family member, about whom Singh learnt only later.

Singh had a cousin sister who during the rampages of Partition jumped into a well to protect her honour. Her father confessed to Singh of nightmares about his daughter each night, screaming from the well, calling out to him. What puzzled Singh was that all these years he had heard about his grandfather’s voice and loss, but not of this 13-14 year-old. Singh wanted to question that the absence of the woman’s identity and voice in the discourse.

Moving on to the idea behind The Song Of Scorpions, Singh confessed that he thought the Kafka-esque end to Qissa was not the only answer he wanted to exist. “I wanted to find a way of dealing with violence where the choice could be something else.”

Further, the horror of the Nirbhaya rape case erupted in him like a dream — images of a man buried in sand, a woman walking, and a melody playing. While attempting to write down the images, the story of The Song Of Scorpions emerged. However, in this film, Singh wanted to bring in his own response to violence. “If I am any of the characters from Ekti Nadir Naam, Qissa, and if I am harmed, what will be my response as an artist? The Song Of Scorpions is really about the choice of an artist to violence in his/her world.”

When the session was opened for questions, Singh was asked how he took care of the format of folktales while scripting the story. “I think folktales tell you the story in terms of images and sounds. It is also not connected to ‘cause and effect’ style of drama. To me the space is also important,” Singh answered, admitting that to incorporate the essence of time and space in a script, he writes for himself. While he writes another script for the producers that is without all these details.

Related topics

IFFK