From the early years of Independence, lyricists and poets have often shaped the cinema conscious public of India with their radical, political, and sometimes, sexual ideology. On the eve of India's 70th Independence Day, we take a look at the lyrics that would never have cleared the stringent laws of the CBFC under Pahlaj Nihalani's regime.

70 years of Independence: Lyrics that defined freedom, but would never clear the first cut today

Mumbai - 14 Aug 2017 14:00 IST

Updated : 16 Aug 2017 14:42 IST

Shriram Iyengar

Cinema, by its nature of being a visual medium, has a more concrete basis upon which it can be censured and controlled. Even the smallest of words can create an issue. As the makers of the recent Shah Rukh Khan-Anushka Sharma starrer Jab Harry Met Sejal found out when the Central Board Of Film Certification (CBFC) asked them to remove the word 'intercourse' from their trailer. While the rest of the internet rushed to create memes, Imtiaz Ali and his team struggled to explain the significance and need of that word in a film about a casanova tour guide and a carefree Gujarati bride-to-be.

The censor board later cleared it, with Ali saying, "Maybe out of context they didn’t like things, but when they see the whole film, they will understand the context and hopefully everything will be okay."

The responsibility of removing, or keeping, songs, scenes and verses in a film lies with the CBFC, which acts on the basis of its committee's interpretation of the Indian Cinematograph Act, 1952.

The recent removal of CBFC chairman, Pahlaj Nihalani, signals a slight change in direction. Yet, it is unlikely that the perspective of the CBFC will shift completely from a conservative attitude to liberal ones. But the growing insecurities of the 'censor' board are a far cry from the liberal sensibilities of the early Independence era, and even later.

Pahlaj Nihalani removed as CBFC chief, to be replaced by Prasoon Joshi

In 2013, there were calls for the CBFC to institute a committee to certify film songs. The Indian Express newspaper quoted a source saying then, "The committee has recommended that while the visual content and the dialogues that precede and succeed such songs are subject to certification, it is only logical to include the lyrics in the ambit of scrutiny."

Songs, in particular, are a key defining element of Indian cinema. They serve to further a scene, emphasise an emotion, or provide relief from a dramatic situation in the film. The lyricist works within the ambit of the director's vision to create poetry that serves this particular purpose. However, lyricists, being poets, often fuse their own vision, ideology, and style to these lyrics creating immortal songs that sometimes outlive their vehicles — films.

70 years of Independence: Walking down the film lane of 1947

Religion

One of the most volatile subjects for lyrics, and poetry in general, is any commentary on religion. In an increasingly divisive India, any comment on religion earns the wrath of the board, the government, and often, extra-judicial authorities on Twitter.

It is ironic that some of the most memorable songs in Indian cinema carry a strong commentary against fanatic and divisive religious beliefs. The early years of Independence saw an influx of writers, poets, artists influenced, and belonging, to the PWA (Progressive Writers' Association) and IPTA (Indian Peoples' Theatre Association) that furthered this train of thought.

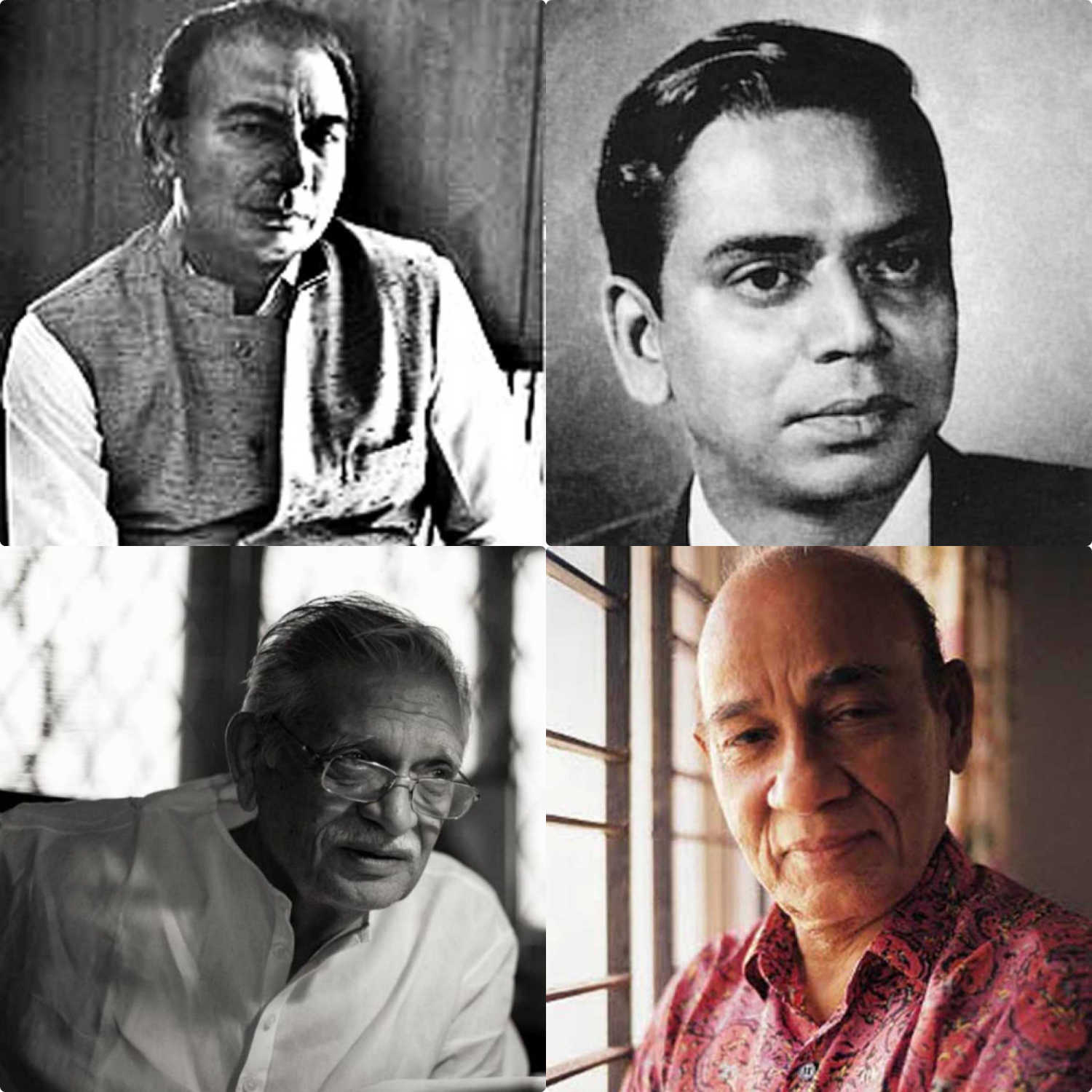

Shailendra, Sahir Ludhianvi, Majrooh Sultanpuri, Kaifi Azmi were among the key names that ruled this era with their lyrics.

The blockbuster Kismet (1943) had already set a trend when it slipped in the patriotic 'Door Hato Aye Duniyawaalon' under the guise of an anti-Axis sentiment. Written by Kavi Pradeep, it caught the eye of the British censor board only after they realised the true meaning of the song, and its sly nod to the Quit India movement.

By the 1950s, this optimism had begun to fade to create a new generation of poets who were averse to singing paeans to patriotism instead of the ground reality. Films like Awara (1951), Shree 420 (1955), Mother India (1957) and Pyaasa (1957) carried within them scars of a nation conscious of the horrors of religious,traditional orthodoxy, and a bourgeouise mentality.

Naturally, the lyrics of several songs during the decade spoke against religious division, and an increased emphasis on humanism. Songs like 'Tu Hindu Banega Na Musalman Banega' (Dhool Ka Phool, 1959), 'Aao Bacchon Tumhe Dikhaayen Jhaanki Hindustan Ki' (Jagriti, 1954), and 'Chaahe Ye Maano, Chaahe Woh Maano' (Dharmputra, 1961) are examples.

Of these, Ludhianvi, a victim of Partition himself, was the most volatile critic of religious fanaticism. Were he to write today, he would have the honour of unifying the extremists on both sides of the religous divide against him.

Akshay Manwani, in his biography Sahir: The People's Poet, quotes director Yash Chopra speaking of Ludhianvi's vitriolic poetry in Dharmputra as 'Sahir was very, very bitter about certain things. Where even certain dialogue writers could not write so powerfully, his poetry did that magic.' (page 146, para 1). In an August 2016 interview to The Indian Express, lyricist Javed Akhtar praised the poet as the one who 'who brought thought to the film song. There is no big gap between his literary poetry and and his songs. Many of his songs are pure literature.'

In Ludhianvi's iconic plaint 'Jinhe Naaz Hai Hind Par' from Pyaasa (1957), he calls for the protection of helpless women pushed into prostitution by evoking symbols from Christianity (Eve), Hinduism (Radha, Yashoda), and Islam (Zuleikha) in the verses

Madad chahti hai ye Hawwa ki beti,

Yashoda ki hamjins, Radha ki beti,

Payammbar ki ummat Zuleikha ki beti ,

Jinhe naaz hai Hind Par Woh Kahan Hai

If that were not enough, in Yash Chopra's Dharmputra (1961), he treads the line with 'Kis kaam ke hain yeh deen dharam, jo sharm ka daman chaak kare/ Kis tarah ke hain yeh desh bhagat, jo baste gharo ko khak kare'. Another verse reads 'Jis Ram ke naam peh khoon bahe, us Ram ki izzat kya hogi/Jis deen ke hatho laj loote, us deen ki keemat kya hogi'. In a country on tenterhoooks post the 1992 Babri Masjid demolition, these verses written by a Muslim poet, despite his atheism, would never have cleared the first cut.

He was not the only one. In Main Nashe Men Hoon (1959), Shailendra writes 'Sharaab peene de masjid mein baith kar/Ya woh jagah bata jahan khuda na ho' (Allow me to drink peacefully in the mosque/Or show me a place without God). While the couplet is borrowed from the 18th century Urdu poet, Mirza Ghalib, it would raise several 'red flags' today.

In the 1970s, religion gave way to capitalistic overtures in films. But there were the rare ocassions like Yaadgaar (1970) where Indivar's verses for 'Woh Khet Mein Milega' pulled down the corrupt priesthoods and blind faith in temples. 'Murti Ganesh Ki' from Takkar (1980), is another wonderful example of lyrics that combined religion and corruption, and yet escaped without any 'suggestions' by the CBFC. At one point, the heroes sing 'Gali me shor hai/ Sadhu nahi ye chor hai.'

When black money was stored inside Ganesh idol and nobody cared

Authority

In a recent interview with the comedy group AIB, Shah Rukh Khan joked that there is a perception that people in the film industry are 'cheats, corrupt'. It was this traditional perception that fuelled, and in turn furthered, the industry's rebellion against authority.

From the first decade of independence, films like Awara (1951), Pyaasa (1957), Do Bigha Zamin (1953) cast aspersions on the ambitions of a new born nation. Their portrayal of poverty, material and philosophical, was only underlined by their lyrics.

Again, Ludhianvi led from the front with songs like 'Cheen-o-arab Hamara' from Phir Subha Hogi (1958). The song was a parody of Iqbal's famous poem 'Saare jahan se accha/ Hindustan hamara'. Ludhianvi's lyrics bite deep into the government's apathy towards its people. As he says 'Jebein hai apni khaali/Deta kyun warna gaali/Ye santri hamara,ye pasbaan hamara' (Our pockets are empty, why else would the cop, who is meant to protect us, curse us).

Whether it is songs like 'Ye Duniya Agar Mil Bhi Jaaye To Kya Hai' (Pyaasa), or Shailendra's 'Dil Ka Haal Sune Dilwala' from Shree 420, songs criticised the bourgeouise regime in favour of the poor, common man.

The loss to China in the Sino-Indian war in 1962 brought in lyrics that spoke up against war. In Usne Kaha Tha (1961), a typical romantic drama, the song 'Jaane Waale Sipahi Se Poocho' has a touch of Wilfred Owens' 'Dulce Et Decorum' as it speaks about the pain of a soldier going off to war. Written by Maqdoom Mohiuddin, the song arrived in 1961, when India was already in the throes of war with China. Today, it would have been suppressed to prevent lowering the morale of the army.

Songs in the 1970s were marked by vitriolic taunts against the establishment. In Roti Kapada Aur Makaan (1974), Verma Malik wrote a brilliant qawwali that described, and criticised the rising prices with the simple, but immortal, verse 'Baaki kucch bacha to mehengai maar gayi'. (If any life was left, inflation took care of it)

This is a contrast to the current CBFC diktat that has asked the words like 'cow', and 'Hindutva' to be beeped out in Suman Ghosh's documentary, The Argumentative Indian, to prevent it from painting a bleak picture of current times.

Wonder what the board would make of Gulzar's biting political satire in the form of 'Salaam Kijiye' (Aandhi, 1975). Incidentally, the song is featured on a female politician modelled on the likes of Indira Gandhi, who was Prime Minister during the dark days of the Emergency.

This was not the only time the lyricist-director had pulled off a satire on the establishment. In his first film, Mere Apne (1971), a story about unemployed young men, he slipped in 'Haal Chaal Theek Thaak Hai'. A funny limerick, it poked fun at the bad economic state of the country and its invisible law and order by saying, 'Aab o hawa desh ki bahut saaf hai/Kaayda hai, kanoon hai, insaaf hai/Allah miyan jaane koi jiye ya mare/ Aadmi ko khoon-woon sab maaf hai' (The country is in good health/There is law and order/God decides who lives or dies/But man has the freedom to kill).

Compare this with the CBFC diktat for 14 cuts in Madhur Bhandarkar's Indu Sarkar (2017), a film that only sought to portray life in the Emergency era, four decades after the event.

CBFC orders 14 cuts to Madhur Bhandarkar's Indu Sarkar, director appalled

Vulgarity

To complain that there is an intolerance to lyrics would be overreaching criticism. The public, and authorities, have been fairly lenient in terms of songs. The 'item song' has now become a regular feature, and often a USP, of films. The growing popularity of songs like 'Chikni Chameli' from Agneepath (2012) and 'Munni Badnaam' from Dabanng (2010) are examples of the phenomenon.

Cabaret numbers progressed from Madhubala's sweet seduction in 'Aaiye Meherbaan' (Howrah Bridge, 1958) to the more sensuous 'Monica O My Darling' (Caravan, 1971). But it was in the 1990s, that vulgarity was well and truly called into public debate.

In 1993, Subhash Ghai's Khal Nayak (1993) ran into trouble for the song 'Choli Ke Peeche Kya Hai' for its vulgar connotations. Feminists were up in arms over the overtly sexual tones of the song. It went on to become a chartbuster.

Karisma Kapoor set the screen on fire with her 'Sexy sexy sexy mujhe log bole' in Khuddar (1994). The word 'sexy' created enough controversy in 1994 to force the makers to change it to 'Baby' for theatrical release. The lyricist for the song, Indivar, also wrote 'Kasme Vaade Pyaar Wafa' for Upkar (1967).

Revisiting 'Mere Desh Ki Dharti' on Gulshan Bawra's death anniversary

At the same time, songs like 'Dhakka Maar' (a not so subtle reference to the act of sex) from Andaz (1994) were released, after the lyricist Sameer added a metaphorical symbol 'maal gaadi' (train) to the song. Not that it changed the meaning much. The producer of the film, co-incidentally was the recently sacked CBFC chairman, Pahlaj Nihalani. The other song from the film, the not-so-subtlely titled, 'Khada Hai' became a weapon for Twitter warriors protesting Nihalani's ban on Alankrita Shrivastava's ode to female sexual freedom, Lipstick Under My Burkha (2017)

The rising popularity of item numbers have seen songs like 'Kaddu Katega Sab Mein Batega' (R...Rajkumar, 2013), 'Laila Teri Le Legi' (Shootout At Wadala, 2013), or the cringeworthy 'Dreamum Wakeuppum' (Aiyyaa, 2012) being cleared and played for public view without much controversy.

In comparison, the censor authorities, in the year of Independence, cut out a whole song from Eight Days (1946) because it had the verses 'Sipahiya raha door kahin jang mein/Joru rahi devariya ke sang mein'. The noted film critics at FilmIndia slammed it as 'a damnable slander of a brave soldier's wife!' (FilmIndia, February 1947). It puts in context the distance covered in terms of flirtatious, and seductive songs. However, it does not explain the contrasting stance of the current CBFC to pass songs such as these, but ask for cuts to the word 'harami' (bastard) in the social drama, Toilet: Ek Prem Katha (2017).

It is this contrasting stand by the CBFC in terms of clearing songs with sexual overtones, but asking lyricists and filmmakers to tone down songs expressing anti-establishment or majoritarian views that earn them criticism.

Take the example of the song 'Fevicol' from Dabanng 2, which is picturised in a red light district, with the lyrics open to interpretation. It remains one of the most popular songs of recent years. Another very popular item number, 'Sheila Ki Jawaani' from Tees Maar Khan (2010) begins with the lines 'I know you want it/But you're never gonna get it/Tere haath kabhi na aani'. In its defense, at least it allows the heroine the leeway to exercise her choice.

However, the song 'Fatak' in Kaminey (2009) ran into trouble with the authorities for its portrayal of sexual innuendoes. Incidentally, the song is placed as part of a street play promoting the use of condoms to ward off sexually transmitted diseases.

Language

Beyond the changing language is the growing use of curse words in lyrics. Rockstar (2011) had the anthem 'Sadda Haq' use the word 'saala', albeit whispered, in it. There is, however, a degree of allowance to the use of these curse words.

Shakti: The Power (2002) saw the use of the word 'kamina' (rascal) in the song 'Ishq Kamina' featuring Aishwarya Rai and Shah Rukh Khan. However, lyricist Amitabh Bhattacharya had to anagram his song to 'DK Bose', in order to avoid using the literal curse word in Abhinay Deo's Delhi Belly (2011). Incidentally, the CBFC cleared the song. It was third party activists who opposed the use of the curse word in it.

In Saba Bashir's 'I Swallowed The Moon', lyricist Gulzar defends the use of such language saying, "A character who is intent on killing, and has the habit of taking out his gun for everything, will not sing 'Dil-e-nadaan tujhe hua kya hai'. He will naturally sing 'Goli maar bheje main...' This context, and setting, often plays a major part in the nature of words used in songs. It also explains the rustic, earthy, and lascivious lyrics that often seep into item numbers which are set at seedy bars, villains' dens, or village dance performances.

Conclusion

At the time of writing this article, Twitter had erupted with a hilarious take by Shefali Vaidya, editor, Swarajya Magazine, who raised a question on the growing use of Urdu, and Muslim imagery in Hindi films. She wrote, 'Remember songs like 'tumhi mere mandir, tumhi Meri pooja'? Now it is all 'ayat', 'ibadat' and 'Maula mere'

To which, a Twitter user, Gaurav Sabnis, put out a hilarious thread of classical Hindi film songs translated with pure Hindi words. For instance he suggested Raj Kapoor's iconic 'Awara Hoon' would be translated to 'Avanichar Hoon/Ya Brahmand Mein Hoon Aakash Ka Taarak Hoon'

Oh my bhagwan! This is indeed a huge crisis! To save our tr00 culture, I shall now start a thread to Hindu-ize some vicious songs. https://t.co/NYZLjiwdJM

— Gaurav Sabnis (@gauravsabnis) August 8, 2017

This growing segregation of 'our culture' and 'their culture' is a dangerous sign. It is further endangered by statements such as CBFC member, Bharat Kundu saying in a Times Of India report, "Over the years, we have lost our self-esteem. I have been a member for over three years and seen people taking liberty in mocking our religion and icons. They don't do that with other religions."

It is no doubt that Indian cinema has grown in parallel to India itself. In many ways, songs from Indian cinema have shaped, and in turn been shaped, by the social, political, and economic conditions of the nation. As the country is racked with incidents of violence caused by cows, women being kidnapped and threatened, and people punished for speaking out, it is hard to believe that this is the seventh decade of India's independence.

As for films and lyricists, the new millenium has seen lyricists and songs being threatened with litigation for the mere mention of colloquial terms in songs like 'teli ka tel' (Kaminey, 2009), mochi - cobbler (Aaja Nach Le, 2007), or symbolic references to something far sinister like the 'white powder' reference in 'Chitta Ve' (Udta Punjab, 2016). This 'offense-taking' needs to be brought to an end. Poets and filmmakers combine to create films that represent the many diverse voices prevalent throughout the country. Lyrics need to be viewed in terms of their context in the film, their references to imagery in the song, and not pulled up on their immediate surface meanings.

In the landmark judgment in favour of filmmaker KA Abbas' documentary, A Tale of Four Cities, in 1970, then Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of India, M Hidayatullah wrote: 'Our standards must be so framed that we are not reduced to a level where the protection of the least capable and the most depraved amongst us determines what the morally healthy cannot view or read. The standards that we set for our censors must make a substantial allowance in favour of freedom... thus leaving a vast area for creative art to interpret life and society with some of its foibles along with what is good.'

40 years later, the battle continues to rage.

70 years of Independence: A look at Hindi cinema from 1940 to 2017

Related topics

Independence Day