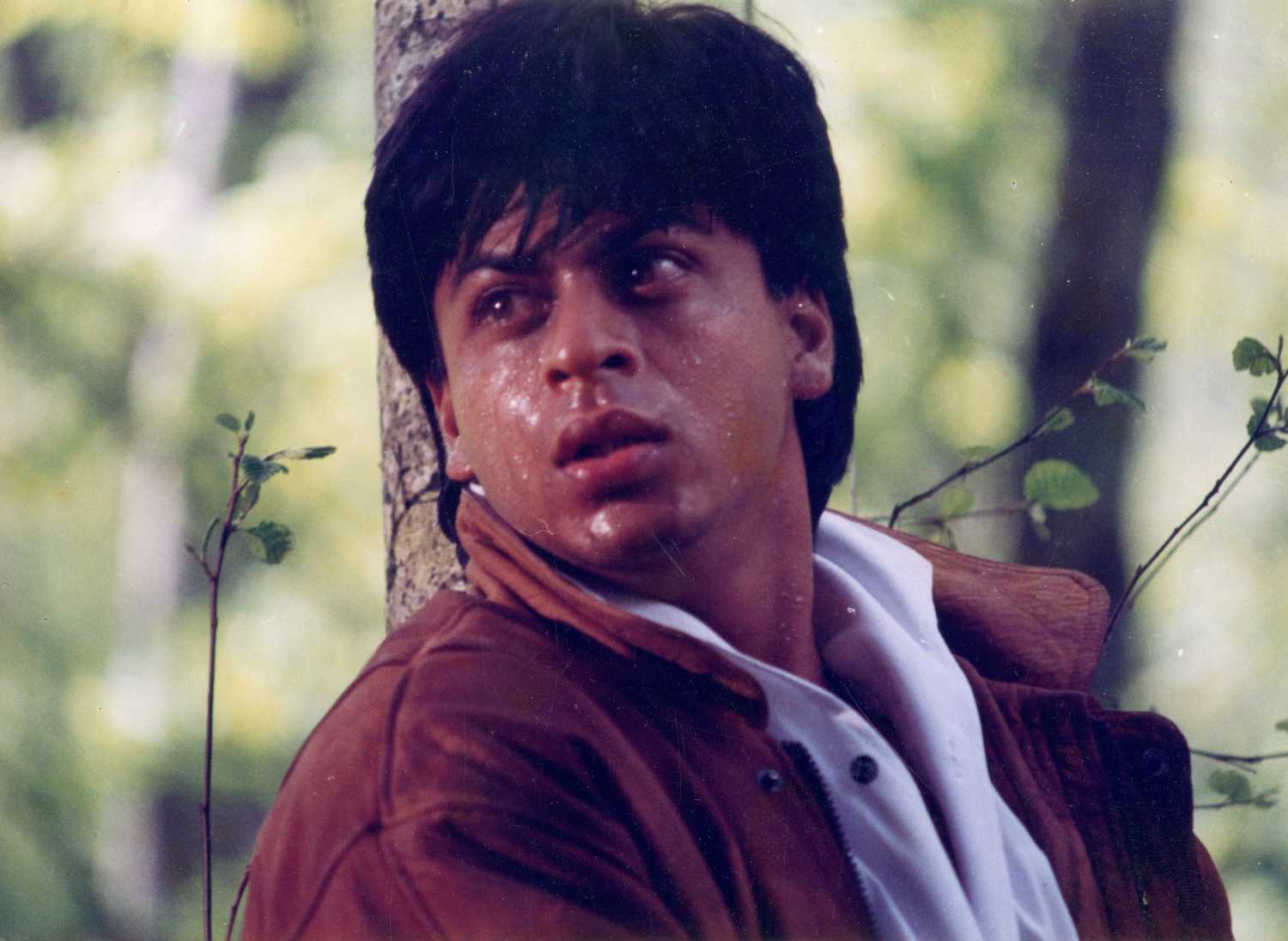

Shah Rukh Khan delivered one of his finest performances as a stalker in Darr. The idea of obsessive love has ruled Hindi cinema for decades, and continues to do so even today. On the 23rd anniversary of Darr's release, we look at the subtext of obsession in Hindi film romances.

Stalking and Hindi cinema's warped idea of romance

Mumbai - 24 Dec 2016 20:00 IST

Updated : 26 Dec 2016 12:15 IST

Shriram Iyengar

- In 2015, an Australian man successfully defended himself against sentencing for stalking two women by saying such behaviour was 'quite normal' for Indian men who grew up on Hindi cinema.

- In August 2016, the murder of an Infosys employee in Chennai for rejecting a stalker's advances shocked the country and raised questions about the culture of stalking pervading Indian films.

The phenomenon of stalking in Hindi films is neither new nor unique. From Amitabh Bachchan pestering Kimi Katkar for a chumma (kiss) in Hum (1991) to Ranbir Kapoor's Ayan stalking Anushka Sharma's Alizeh in Ae Dil Hai Mushkil (2016), stalking has been an integral part of Hindi cinema's idea of romance. Yet, somehow, every discussion on stalking in cinema seems to be centred on Shah Rukh Khan's performance in Yash Chopra's Darr (1993).

For many, Darr remains the prime example of Hindi cinema condoning stalking. Yet, it was the death of the obsessive lover that made it so real. The film climaxed in a brutal death that would have presumably left a permanent scar on the psyche of the young woman, played by Juhi Chawla, who was the object of Khan's obsession.

Stalking is one of the many social evils that Hindi cinema is often blamed for promoting, others being smoking and alcoholism. However, the trouble lies deeper, in the gender equations prevalent in Indian society that normalize stalking to a large section of the population. Men are expected to "take control" of the courtship while women are supposed to follow a more submissive role. The statement, "ladki ke naa mein bhi haan hai", is one that has been heard through the ages. So, to call this a recent phenomenon would be to deny its antecedents.

Take the film Paying Guest (1957), starring Dev Anand and Nutan. One of the more famous songs from the film goes: 'Maana janaab ne pukaara nahin,

Kya mera haal bhi ganvaara nahi'

It goes on to establish that though the woman never did invite the 'hero', he would still follow her around and impress her. The same is the theme with another classic song, 'Chhod Do Aanchal', from the same film.

This remains, broadly, the template for romance by the hero in a Hindi film. As the years went by, this tendency only morphed into more aggressive modes. Take, for instance, Sholay (1975). The epic, considered by many to be the greatest Hindi film, has a macho Dharmendra pursuing Hema Malini despite her obvious resentment of his actions.

Comedy group AIB recently put out a video on how stalking has been condoned in Hindi cinema through the ages.

Aanand L Rai's Raanjhanaa (2012) revolved around Kundan's (Dhanush's) obsessive stalking of Zoya (Sonam Kapoor). Despite her rejection of his advances, he continues to pester her, slitting his wrists, even disrupting her engagement, which results in the death of her fiance. While the film has gone on to become a cult hit with the masses, critics were appalled at the apparent justification of stalking as a form of love.

In his defence, Rai said, "My only thing was people who were talking about the so-called stalking and all that stuff haven't seen Banaras, they haven't seen the people of Banaras. They don't know that middle class, that youth, that innocence, their lifestyle, their nature, their culture."

Rai is not entirely wrong. Baradwaj Rangan, National award-winning critic, points to a similar socio-cultural problem that is reflected in cinema, not caused by it. In a blog post following the fury at the murder of the Infosys techie in Chennai, Rangan wrote, "Correlating films and society is a chicken-and-egg conundrum.... We need to study why so many people remain impervious to the good things cinema says – vote wisely; abolish the caste system; don’t do drugs – and take home only messages like 'smoking is cool' and 'girls who say no are really saying yes'.”

In Raanjhanaa, Kundan compares himself to Darr's Shah Rukh Khan, obsessively pursuing the object of his unwanted affection until she gives in and says yes. It is a remarkable comparison, and a statement that sheds light on the mind of the small-town Romeo who idolises Hindi cinema's 'King of Romance'.

Darr was among the more blatant, and extreme, depictions of stalking on screen. Playing the obsessed lover, desperate to get his girl or kill her, Khan brought a sense of malice, venom and possessiveness that launched him to superstardom. This role was not a one-off either. Khan followed it up with films like Baazigar (1993), Anjaam (1994) and Ram-Jaane (1995) that were glorified stalking guidebooks. Even the soft-hearted romances of Kabhi Haan Kabhi Naa (1994) and the blockbuster Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (1995) displayed symptoms of this malaise.

Shah Rukh is not the first, nor the last, of the three Khans to play the obsessive lover. It seems to be a necessity for a star in Hindi cinema to establish his credentials by playing such a role. Aamir Khan played one in the flop Deewana Mujhsa Nahin (1990) while Salman Khan began his rebirth in Hindi cinema by playing an obsessed lover in Tere Naam (2003).

To say that the industry doesn't realise the danger of this portrayal is wrong. Actor Siddharth of Rang De Basanti (2006) fame reacted to the Chennai murder by pinpointing cinema as one of the causes. In a tweet that was widely shared, he wrote: 'The truth is a lot of stalking in real life is inspired by what we show in our films. Too many examples of justification.'

We've been selling a terrible dream in our films for long. That any man can get the woman he wants just by wanting her enough. Must change!

— Siddharth (@Actor_Siddharth) July 17, 2016

To be sure, the obsession with love makes for a dramatic story. In Karan Johar's controversial Ae Dil Hai Mushkil (2016), Ayan's obsession with Alizeh defines the story's emotional crux. In the National award-winning Tanu Weds Manu (2011) and its sequel Tanu Weds Manu Returns (2015), R Madhavan plays a passively aggressive doctor who pursues a free-spirited woman played by Kangana Ranaut.

The irony of Ranaut being accused of stalking in a public break-up by another star, Hrithik Roshan, is hard to miss. The actress opened up in public about her relationship and the bitter break-up that followed. It earned her scorn and derision on Twitter, a pointer to the sociological angle to the problem. In a country where women continue to be, largely, secondary citizens, it is natural that an independent woman's open challenge to a popular actor will not be easily accepted.

On the 20th anniversary of Darr's release, Yash Raj Films had announced Darr 2.0, a web-series sequel about stalking in the virtual age. Thankfully, Darr 2.0 never made it off the storyboard.

Although stalking remains a big issue, the last couple of years have had a number of films portraying women of courage and character. Queen (2014) is the best example of this new flow of ideas. As a new generation takes to Hindi cinema, with Ranbir Kapoor and Ranveer Singh as its icons, it is necessary to correct the direction of one of the most powerful media of mass communication. Change may be slow to come, but it is coming nonetheless.