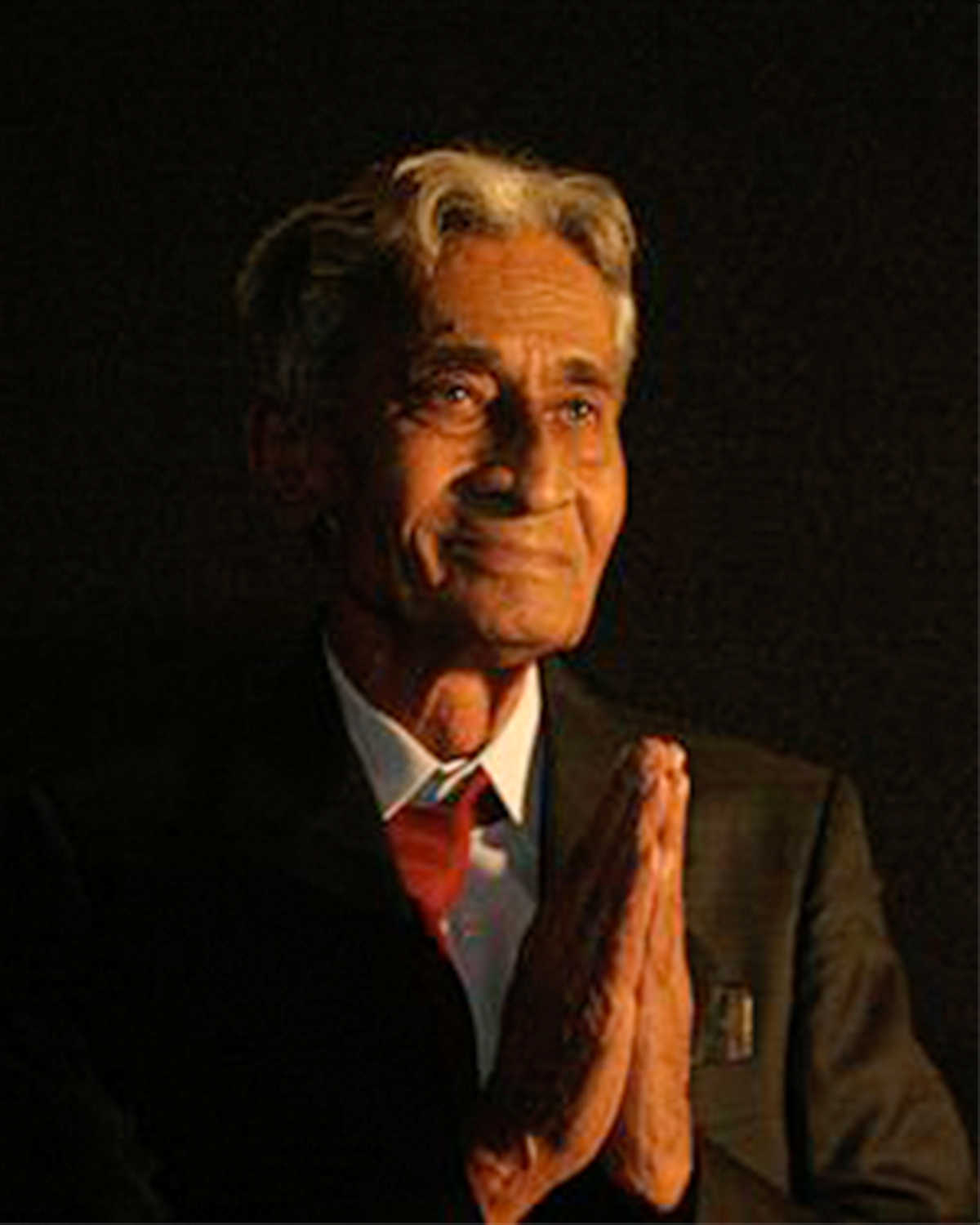

The man behind some of the most iconic images of Indian cinema, V.K. Murthy would never have made it to the film world were it not for the one instrument he is never known for — his violin. Here's how it helped one of India’s greatest cinematographers to step into the limelight

Shriram Iyengar

‘He was Guru Dutt’s eyes’ says Nasreen Munni Kabir about the cinematographer V.K. Murthy, in her ‘Conversations with Waheeda Rehman’. A statement that is as metaphorical as it was literal, it describes the role a cinematographer plays in bringing his director’s vision alive. Students of Indian cinema are only too familiar with the name of V.K. Murthy. His ability to transform a simple scene into a metaphorical statement using the most innovative camera techniques made him one of the most respected cinematographers of his time. But this career would not have been possible if not for the most underrated tool in the cinematographer’s kit - his violin.

His journey into films would have made for a gripping film script. A rags to riches story, Venkatrama Pandit Krishnamurthy’s life took him from the quiet, sedate suburb of Mysore to the glitz, glamour, and starry heights of Mumbai’s film industry. The camera was not Murthy’s first choice for entry into the cinema. As a 15 year old hero wannabe, he ran away from home to join a film course in a Bombay college. All he had with him were the details of an advertisement and the address of a relative. “I had seen an advertisement in the newspaper for something like a film institute where all the departments were going to be taught, including acting.” he said in an interview in Dec 1999. Luckily for him, the relative was kind enough to allow him to try and find a job in the industry. Sadly, it didn’t work out. After a couple of months treading the pavement outside studios, Murthy returned home.

Not that all was quiet on the home front. His father's retirement meant that the family was struggling financially. It was during this time that the young cinematographer turned to his first love, music. He says “But the main thing at that time for me was that I loved music. I was learning to play the violin. Luckily for me, that year they had introduced music as an optional subject and this helped me a lot. I was bad in all subjects, especially science, maths and history. I was only good at art and music in school and secretly wanted to become an actor. Frankly, I would have failed in school if music as an optional subject had not been introduced.”

His passion for cinema was unharmed despite the failed trip to Mumbai. Murthy would spend hours after school working at a theatre near home selling tickets while catching some movies on the sly. Like. Having given up on an acting career, Murthy turned his attention to the technical aspect of the camera and the violin. Ironically, it was the latter instrument which opened the doors to his film career. Years later, when he was studying cinematography at the Jayachamarajendra Technical Institute, the violin was his only luxury. As he says in his biography, 'Basilu Kolu' written in Kannada, “I got free boarding at one students' hostel because I impressed the trustees with my brilliance with the violin. I also became very popular as a student because I would also conduct orchestras and plays.” Soon, he became a part of the travelling troupe of Ram Gopal, a dancer contemporary of Uday Shankar. The master of fluid camera movements and the innovator of the magic ‘beam of light’ technique, was reduced to an unpaid accompanist on the troupe! But unknown to Murthy, Lady Luck had taken a shine to him.

It was during one such All India dance meet that Murthy was introduced to music composer Sardar Malik by Mohan Sehgal, the brother of danseuse and actress, Zohra Sehgal. Sardar Malik proved to be his entry card into the industry, and Murthy joined Malik's composing team as an additional musician. Several months later, Malik would introduce him to the famed cinematographer, Dronacharya. The elder cinematographer offered the young man an interns hip as the fourth camera assistant for the film ‘Maharana Pratap’ (1942). Murthy would later say “So you see, if I had not played the violin, I would never have been able to afford staying in Bangalore - it paid for my food, and if I had not played the violin with Ram Gopal, I would never have met Mohan Sehgal, and if I had not met Mohan Sehgal, I would never have met Dronacharya and If I had not met Dronacharya I would probably never have got work in the camera department. Music has been very lucky for me.”

hip as the fourth camera assistant for the film ‘Maharana Pratap’ (1942). Murthy would later say “So you see, if I had not played the violin, I would never have been able to afford staying in Bangalore - it paid for my food, and if I had not played the violin with Ram Gopal, I would never have met Mohan Sehgal, and if I had not met Mohan Sehgal, I would never have met Dronacharya and If I had not met Dronacharya I would probably never have got work in the camera department. Music has been very lucky for me.”

Within the decade, Murthy would be spotted by Guru Dutt on the sets of Dev Anand’s ‘CID’. It would begin one of the most beautiful and productive artistic partnerships in Indian cinema. The two would combine to create some breathtaking films that would redefine the idiom of cinema in India. The man with the violin would assist Guru Dutt in composing some of the most breathtaking visual symphonies Indian cinema has ever produced.